By Payton Suire Managing Editor

Eight years before Last Island was destroyed by a hurricane, the Voisin family began a land dispute that wouldn’t end for almost two centuries.

In 1848, people began to question who owned Last Island when the State Land Office began selling tracts of land on Isle Derniere. Jean Joseph, J.J., Voisin, son of an eighteenth century French immigrant, confronted the purchasers, Thomas Maskell and James Wafford insisting that his family owned the island, which had been in the family for 70 years, by a 1788 Spanish land grant.

In the Public Land Claims, it says “a Juan Voisin, una pequeña ysla, vulgarmente llamada L’Isle Longue . . .” (“to Jean Voisin, a small island, commonly called L’Isle Longue . . .”). The claim describes the location of Isle Longue as “situated in the Lake of Barrataria, adjoining (or contiguous to) on one side Last Island, and on the other, fronting the island called Wine Island.” On July 1, 1833, J.J. Voisin submitted documentation for claims on two tracts of land: Pointe-à-la-Hache and Isle Longue.

A neighbor, Charles Carel, someone well-acquainted with the island, made an affidavit, “it has always been in his [Voisin’s] possession or in that of those who held it for him,” The 1788 order of survey and testimony supported Voisin’s two claims. In 1835, Voisin made another claim to the land when the U.S. Congress enacted legislation confirming the original grant, according to Public Land Claims Number 4533.

In November of 1837, Gilmore F. Connely, a deputy surveyor, contracted with the State Land Office to survey portions of Terrebonne Parish, including “all the islands on the coast.” Four years passed before the surveys were certified, and two years later in 1844, the State Land Office added a second annotation to the west end plat. Last Island was for sale, according to the Last Island Survey Plats.

The increased demand for land on the island corresponds to the “discovery” of the island’s sandy, white beaches. By 1846, steamboats and sailboats regularly took visitors to the island. Some began constructing cottages or summer homes along the beach. Last Island’s popularity spread, and on April 8, 1848, St. Mary Parish sugar planter, Thomas Maskell, purchased 160 acres for about $200, worth about $6,600 today, according to the Bethany Bultman Papers about Isle Derniere.

On July 13, 1848, James Wafford purchased 53 acres west of Maskell. When confronted by Voisin, one purchaser, Alexander Pope Field, used a military warrant to claim his 100 acres and a Louisiana Surveyor, Gen. R. W. Boyd for a ruling. Boyd explained that in his office’s survey of Last Island, there was no survey or knowledge of Isle Longue.

In the Public Land Claims, Voisin’s lawyer, F.C. Laville, questioned when he could expect to receive his patent but went months without reply. Boyd finally replied stating an island named Isle Longue “has not yet been surveyed.” This explanation failed to impress Laville who explained the name of Isle Longue had changed over time to L’Isle Derniere or Last Island, but the argument failed. The dispute intensified when Voisin moved his family to Last Island in 1849.

In 1854, Wafford’s attorney filed suit in Houma to evict Voisin from his property and assess the damages from his actions. On November 28, 1854, Voisin’s attorneys filed a civil suit countering the claims of Wafford declaring Voisin to be the “true and lawful owner” of an island “wrongfully” called Last Island. They presented three documents: the 1788 Order of Survey, the Register’s recommendations, and the 1835 Act of Confirmation and asked for 3,000 dollars in damages, about 93,000 dollars today.

As the chaos and contradictions ensued, the 1855 court calendar came to a close with each side eager for a winter break from court proceedings. The judge announced the case would resume in 1856 — the year the Last Island Hurricane hit.

“Within weeks, the slow-moving trial would be upstaged by another slow-moving presence, a large counter-clockwise cloud formation stirring in the eastern Gulf ofMexico. A huge storm was inching slowly toward Louisiana’s central coast,” according to The National Hurricane Center (NHC) the Atlantic Hurricane Database Reanalysis Project.

“After the storm, I think he just lost interest in it,” said Jeanette Voisin, a descendant of

J.J., in an article by Houma Today, who is fighting for the land rights. “Everyone died out there. No one wanted to go back.”

According to the book “Last Days of Last Island,” South Louisianians lost interest in the ownership of Last Island in the storm’s aftermath. The entire village was washed away in one afternoon leaving the trial to end gradually. In 1859, a judge postponed the case indefinitely due to the parish being invaded by the North as the Civil War ensued.

After the Civil War, the dispute was reopened one final time, but most of the litigants and witnesses were dead, old, sick or weak. The judge placed the trial on a “dead docket” constituting neither a dismissal nor termination of the case in which it can be reinstated at any time. The file of documents, testimonials, and maps would remain untouched for generations.

Flashforward to 1988, James Voisin was gathering information for the Voisin family tree when he found a spotted, faded brown pocket folder with a file titled “Jean Joseph Voisin versus James Wafford, et al.” He recalled a story his father, Everett Voisin, told him.

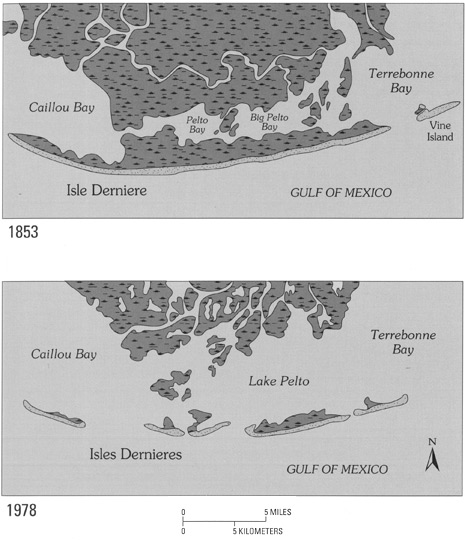

During the ’50s and ’60s, Everett Voisin operated crew boats in the Atchafalaya River Basin when a coworker showed him an offshore drilling map with the name “Voisin” penciled along a small island situated in the middle of Isles Dernieres. Everett never pursued the information. Who Owned Last Island? Solving a Centuries-Old Louisiana Puzzle.

Twenty-five years later, James Voisin shared the story with the rest of the family, which, after months of discussion, decided to engage an attorney. In late 1989, Lexington attorney Tim Hatton wrote to the Bureau of Land Management on behalf of the Voisins.

“Jean Voisin received an order of survey to Last Island from the government of Spain in 1788. In 1833, he applied to the U. S. Government for a patent . . . pursuant to a statute passed by Congress in 1832. For some reason, a dispute arose over ownership of Last Island and the property may have been patented to others. I would appreciate any information that your office may have concerning severance of Last Island, Louisiana from the public domain,” according to the suit.

On February 21, 1990, the Bureau’s Eastern States Office in Springfield, Virginia, responded that they had no jurisdiction over lands after they have been patented, and the title vests in the patentee, so the Voisins began a search for the title location. In May, 1996, the Bureau of Land Management announced it was “unable to locate the claim of Jean Voisin.”

Still, on May 12, 2011, the determined descendants of Jean Joseph refiled a civil action in the United States District Court, Eastern District of Louisiana.

After 150 years, the family was hoping for closure. About 350 descendants of Jean Voisin, many who lived in Terrebonne Parish, would have been affected by the verdict. In 2006, the land was under ownership by the state of Louisiana, with the most recent title holder being Louisiana Land and Exploration Co., which received 50 percent of oil royalties, according to Houma Today.

“This time we’re asking the federal government to acknowledge the fact that Last Island

does belong to the Voisin family,” said Jeanette Voisin in the 2006 lawsuit. “We’re not asking them for money, we’re not asking them for anything else.”

According to Houma Today, James Voisin, Sr., a descendant of Jean Joseph Voisin, spent years researching the family’s claim to Isle Longue before he died in 2009. The suit was filed on behalf of James Voisin Jr., his son, and a cousin, Charles Johnson. Jeanette Voisin, James Voisin Sr.’s wife, continued the fight her husband began “to force the government to correct a longstanding error that disenfranchised generations of Voisins.”

“He wanted to right a wrong; he often told me that. It’s not about money,” Jeanette Voisin said in Houma Today. “Why shouldn’t we right a wrong?”

“I really just want to have the property back in name,” said Juliet Henry, the

great-great-great-great granddaughter of Jean Voisin, to Houma Today. “To prove once and for all that it did belong to my family.”

Henry, though not involved with the court proceedings, has been so fascinated with her family’s story that she wrote a historical fiction novel titled “In the Shadows of the Trade Winds” that includes J.J.’s fight for the island, as well as his personal account of being on the island when the storm hit.

“People would talk about Jean and J.J.,” Henry said in Houma Today. “I knew I had to write the story.”

According to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Isle Dernieres Barrier Islands Refuge is now owned and managed by the LDWF.