By Emilee Theriot, Staff Writer

In addition to a bounty of fish, animals and plant life above ground, the earth beneath Grand Bayou is rich with natural resources like salt domes, natural gas and oil.

“Wherever you have a salt dome, somewhere along the line there is oil and gas,” Jerry Rousseau, a Grand Bayou resident, says.

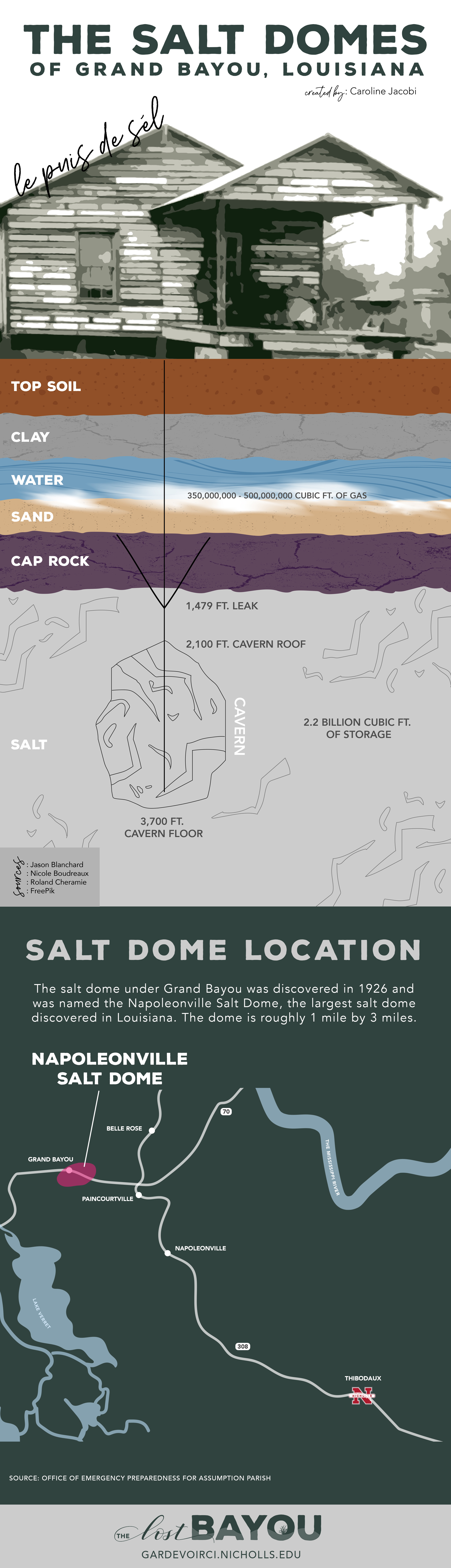

The first salt dome in Assumption Parish, which became known as the Napoleonville Salt Dome, was discovered in September of 1926, according to a 1927 article in The Assumption Pioneer. The largest of the 68 salt domes discovered in Louisiana, the Napoleonville Salt Dome was about one mile by three miles. It began at 700 feet below the surface and went to a depth of 30,000 feet.

Dow Chemical began purchasing the land above and around the salt dome in 1956, according to the conveyance records at the Assumption Parish Clerk of Court office. The company purchased 103 acres from Schwing Lumber, a large landowner in the area, and 169 acres from the Leblanc family as well as several hundred acres from dozens of families. Each act of sale included language that the sellers reserved a five-cent-per-ton royalty from the sale of the salt removed from the dome.

Dow wanted the salt domes to use the brine in making plastics in their chemical plants along the Mississippi River, Rousseau says.

To mine the salt, the company drilled a well in Grand Bayou and pumped hot, fresh water into the salt dome, which eroded the salt from the dome, says John Boudreaux, the director of the Office of Emergency Preparedness for Assumption Parish. The mixture of the fresh and saltwater created a solution called brine. A second well was drilled from above ground and entered the new salt cavern to retrieve the brine. The brine was pumped out of the salt cavern into above-ground storage tanks.

Once above ground, the brine was shipped by truck to the Dow Chemical plant in the nearby city of Plaquemine in Iberville Parish. The plastics produced using the brine were shipped from the plant along the Mississippi River to various other plants throughout the United States. The plants would then use the various plastics to make consumer products like toys, paint and appliances.

This system worked for many years. But as salt was removed from the dome,it left an empty cavern within the salt dome, Boudreaux says. And a typical cavern is the size of 50 Mercedes Benz Superdomes — underneath homes and communities. Then in the 1960s and 1970s, various oil companies leased the caverns from Dow Chemical to store oil and gas.

With the dome so big, Dow allowed Texas Brine to begin extracting brine from the Napoleonville Salt Dome in the 1960s. Rousseau’s father was the first employee at the Texas Brine Grand Bayou facility.

“My dad’s job was to make sure the plant was run correctly,” Rousseau says. “Trucks would come in and pump the brine into the tanks and bring them where they needed to go.”

Now, most of the brine is transported via pipeline. Brine continues to be removed from the salt dome and delivered to chemical plants along the Mississippi River in Taft, Geismer, Gramercy and Plaquemine. The more brine removed allows for more oil and gas to be stored.

Today, there are over 60 caverns located in the Napoleonville Salt Dome. Boudreaux says a few more permits are pending to develop more caverns in the Napoleonville Salt Dome.