by Payton Suire Managing Editor

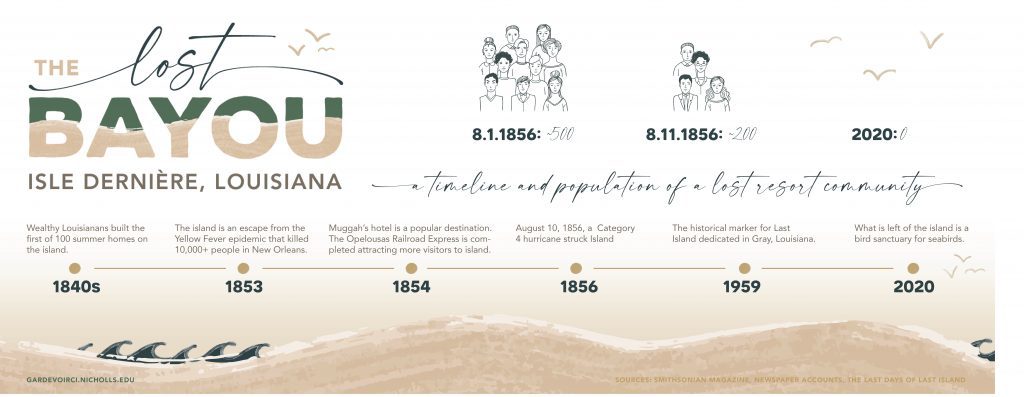

At one time, Louisiana’s coast was a white, sandy beach and blue-water destination. An oasis for the rich and powerful sugar planters. But the beauty of this paradise and the wealth of its visitors provided no protection from the deadliest storm to hit Louisiana’s coast. This unnamed storm that erased the summer resort of Last Island, Isle Dernière, was the worst to hit Louisiana until Hurricane Laura in August 2020.

“Those storms all have become legendary. It’s part of your psyche now. The difference between 1856 and any of those other storms that impacted LaFourche Parish, is that, and I say politely, those people could read and write,” said John Doucet, author on early Louisiana hurricanes and dean of Nicholls State University’s College of Sciences and Technology. “They say that 2/3 of all the millionaires in the United States lived in Louisiana at the time. Much of the wealth of the United States diminished that night. First because of the death of the planters, but also, when a planter dies, the wealth has to be divided between the children.”

Today, weather forecasters use data from radars giving residents days to prepare. Laura was tracked in the Gulf of Mexico more than a week before the storm hit. And while predictions and models are still imprecise — for Laura, hurricane warnings were in effect from New Orleans to the East Texas coast — any advance warning gives residents and officials time to order evacuations. 500,000 people during Laura were evacuated and prepared, according to news reports. Unfortunately, in 1856, the vacationers on Last Island were naive to the tragedy forming in the Gulf and largely unaware of what was to come.

Despite the warnings from crew on the steamboat Nautilus, capsizing only a few miles off the island, the cows pacing and lowering in the fields, or the waves as high as houses forming on the horizon, resorters believed everything was perfectly fine, according to the book Remembering Last Island. Even while the storm moved onshore and the winds swirled, vacationers partied at Muggah’s Hotel, the most popular spot on the island.

“We did not know then as we did afterwards that the voice of those many waters was solemnly saying to us, `Escape for thy life,'” said survivor Rev. R.S. McAllister of Thibodaux, Louisiana in his memoirs A Minister Tempered by the Elements.

Within two minutes water covered the island, washing away all structures and wildlife. Of the 400 on the island, 198 were dead, according to the 2017 Smithsonian Magazine article, A Hurricane Destroyed this Louisiana Resort Town Never to Be Inhabited Again. Those who survived barely escaped, witnessing the fate of those around them. In those times, the only way on and off the island was by boat and help took 5 days to arrive, leaving survivors scattered in the marsh, many injured, living off of crawfish and rainwater.

“The jewelled and lily hand of a woman was seen protruding from the sand, and pointing toward heaven; … and again, the dead bodies of husband and wife, so relatively placed as to show that constant until death did them part, the one had struggled to save the other,” McAllister says. “And, more affecting still, there was the form of a sweet babe even yet embraced by the stiff and bloodless arms of a mother. Sights like these suddenly presented, gave a shock never to be forgotten, and called up certain feelings which no language can describe.”

Even today, southwest Louisiana’s hurricane-Laura ravaged areas are still digging out from the debris and destruction a month after the storm hit.

Last Island, which was completely submerged and broken into multiple pieces, never again housed a community. The only evidence of the short-lived, yet vibrant resort oasis is the historical marker erected in 1959 in Gray, about 45 miles north of the former Last Island. The small strips of sand that once formed a single island are now a bird sanctuary for pelicans and other water birds.