sarah kraemer features editor

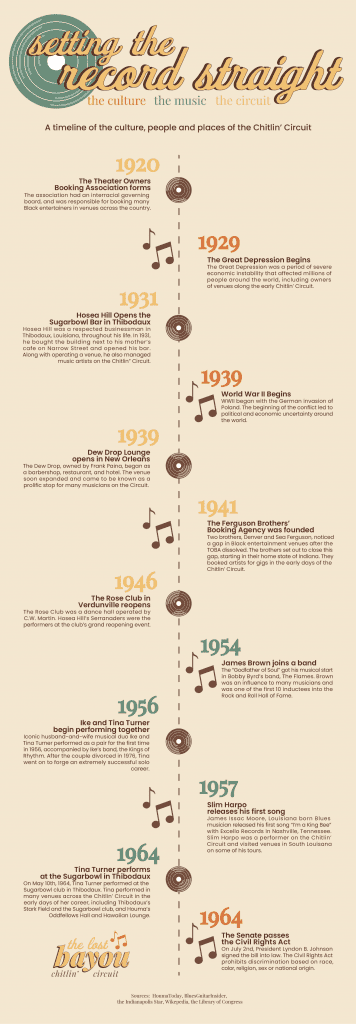

The 1930s to the 1960s were the height of blues, jazz, R&B and rock ‘n’ roll music.

It was also the height of Jim Crow segregation in the South.

In a time when Black musicians could not perform at popular, career-making venues, these musicians had to find unique ways to play for audiences. Because of this, performers and venue owners created an “underground” network of live entertainment locations now called the Chitlin’ Circuit.

Small venues on the circuit were located everywhere from Texas to Florida to Massachusetts to the small Louisiana town of Thibodaux.

Thibodaux “was like a base on a baseball field” for black musicians, says Jeff Hannusch, author of “The Soul of New Orleans: A Legacy of Rhythm and Blues.”

Thibodaux was home to various stops on the Chitlin’ Circuit, like the Sugar Bowl, that were kickoffs for musicians’ careers — impacting the musicians, the residents, and the culture of the area itself.

“The music was unpolished, but that’s what made it so good. It was the real thing. It was reality.”

Jeff Hannusch

Thibodaux is in the heart of Bayou Lafourche, that area south of New Orleans that most of the U.S. believes sits in the water.

This Cajun town has a community that fosters a unique music culture.

These characteristics made Thibodaux a prime area for African American musicians to perform during Jim Crow segregation, especially with the financial help and moral support of the Sugar Bowl Owner Hosea Hill, Hannusch says.

After The Great Depression, the Great Migration of Black Americans from the South to the North corresponded with a migration of rural black Americans to cities like New Orleans.

“Between 1920 and 1940, the New Orleans black population swelled from 100,000 to 150,000,” according to “A Closer Walk,” a non-profit website focusing on New Orleans’ music history.

Among those migrating to the Crescent City were young people from small towns, like Thibodaux, who would become some of the most influential blues and R&B artists of the time.

This migration led to venues owned, run, and visited by Black Americans in these cities and their rural feeder towns.

Hannusch, a New Orleans resident, says people would get dressed up to “raise hell” and listen to these musicians.

“The music was unpolished, but that’s what made it so good,” Hannusch says. “It was the real thing. It was reality.”

This music and these venues became a part of the Black culture of the time, especially in an era before entertainment media like TV and the Internet.

93-year-old Mary Anne Hoffman says she remembers her friends attending circuit performances.

“At the time, it wasn’t proper [for white people] to go into those places, but a lot of my friends went and participated in that,” says the Thibodaux native.

Those stepping over the segregation lines could face serious consequences.

“You would have to take a chance,” Hannusch says. “A lot of those guys ended up in jail for the night.”

Because of the fear of crossing segregation lines the circuit had an air of secrecy and the stories of the musicians and their impact have also stayed hidden.

Today

Thus, today the essence of the Chitlin’ Circuit is mostly lost and unspoken.

Hannusch says that’s why he began his research.

“It was ignored by a lot of people at the time…and now,” he says.

This, along with the normal passage of time, means those who experienced the Chitlin’ Circuit firsthand are gradually taking those memories to their graves.

“I had several friends that I know would know so much, but… they’re either dead, or I can’t reach them,” Hoffman says.

The music and the memories of the circuit’s culture can be told, however.

Like a vinyl record created by musicians with accuracy and care, the story of the Chitlin’ Circuit can be recorded by those who experienced the music and by those impacted by the culture of the musicians who created it.

This issue of Garde Voir Ci will do just that.