Brogan Burns features editor

Louisiana is home to the fastest-disappearing land mass in the US, stretching from Plaquemines and Lafourche parishes as far north as Point Coupee and home to over 600,000 people.

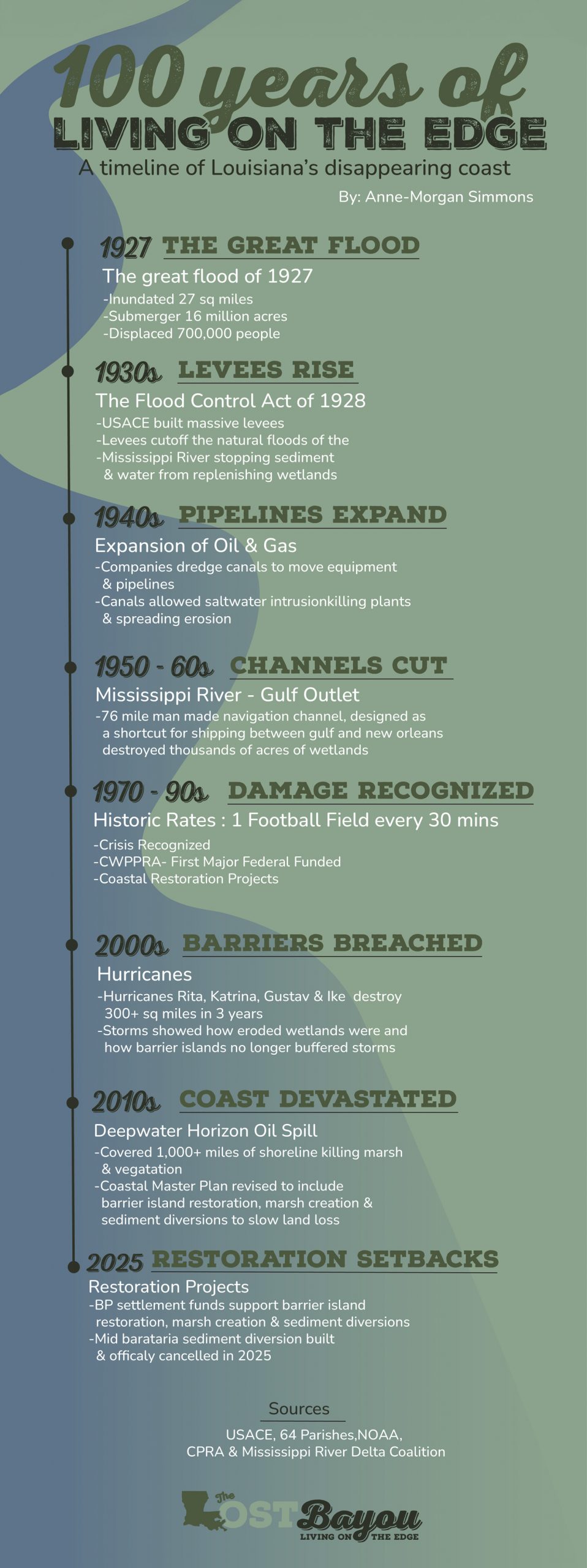

The Louisiana coast has been experiencing this crisis for the better part of the last century and likely longer than that. Between 1932 and 2016, Louisiana lost 2,006 square miles of its coast, an area equivalent to more than 10 times the size of New Orleans, according to a 2016 study produced by the U.S. Geological Survey.

“A whole lot can be lost without it being noticed; that way, people don’t get alarmed,” says Gary LaFleur, a biology professor at Nicholls State University in Thibodaux.

“A whole lot can be lost without it being noticed; that way, people don’t get alarmed.”

Gary LaFleur

An Invisible Crisis

Despite the problem beginning decades ago, it was not until 2007, two years after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated Southeast Louisiana, that the state began to fund a master plan by the Coastal Protection and Restoration, which says the plan has an “emphasis on improving protection from storm surge-based flooding and creating a sustainable ecosystem.”

The time elapsed from the start of the crisis to the funding of a state restoration plan is due to Louisiana’s unique geography.

Unlike most of the world, Louisiana’s coast is made up of soft marshland, which struggles to hold up the weight of a person, making permanent settlement impossible. Lack of use of the coastal land has left its disappearance unnoticed, allowing coastal erosion to fester quietly, leaving a fast-moving crisis, LaFleur says.

Causes

Geography left the extent of the crisis relatively unnoticed, but a range of factors, both natural and mostly man-made, are to blame for the large losses of land.

Sediment displacement and subsidence are the surface-level reasons for the crisis, but both causes find their roots in man-made changes to the land and waterways, known as hydrological modifications. The most used form of these modifications is levees.

“Human hydrologic modifications have led to this accelerated subsidence, which is like sinking,” LaFleur says.

French settlers learned early in the 1700s that land along the Mississippi River is flood-prone, building the first levees in New Orleans in 1719, only two years after founding the city. Originally, these levees were used to protect life and property, but over time, they led to sediment displacement.

Natural flooding of the Mississippi River deposited sediment in the flooded areas, replenishing and building land; however, with levees restricting its natural flow, sediment is going out of the delta and into the Gulf of Mexico. Without the sediment being naturally deposited, it has allowed erosion and land degradation, which has forced the land to subside.

Although human-made causes have accelerated the land-loss crisis, natural and environmental

Factors can not be ignored. Hurricanes and sea level rise have played a constant role in the crisis.

Hurricanes are large, catastrophic events that have the power to displace tremendous amounts of land and also destroy entire barrier islands, says LaFleur. Sea level rise accelerates the crisis at a much slower, but more constant rate. Water rise meets subsidence, sinking the land much quicker than subsidence alone.

Environmental stressors such as the introduction of the invasive nutria rat and the pervasiveness of offshore oil drilling are smaller, yet key factors.

Politics

Coastal scientists and activists have worked for years pitching and creating restoration projects. Still, in recent months, Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry effectively killed two of these projects, according to Restore the Mississippi River Delta.

The Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion and Mid-Breton Sediment Diversion projects had their permits suspended this year, halting years of progress.

Tyler Duplantis, a Houma resident and member of the United Houma Nation, believes that with the coast and other environmental issues becoming politicized in recent years, it is important to ignore the politics and come together to protect the coast and its people.

“We need to educate people on the matter and not look at it as political, but instead as keeping our Bayou community strong,” Duplantis says. “I like to think in Louisiana, we are united as one family, and if one of our family members has to relocate because of land loss, we have to take care of them by realizing the problem and fixing it.”

“I like to think in Louisiana, we are united as one family, and if one of our family members has to relocate because of land loss, we have to take care of them by realizing the problem and fixing it.”

Tyler Duplantis

More than Land

As land recedes from the coast, water is allowed to move further inland, resulting in changes to the lives and cultures of those affected.

Flooding became, at times, a daily challenge for Former Grand Isle resident Rhiannon Callais, who says she would often wade through water when a not-so-unusual high tide flooded parts of the island. This flooding could often force children to miss school, as buses were unable to reach students.

Point aux Chenne in Terrebonne Parish is a prime example of the effect land loss has had on people.

The Island, which was home to members of the Biloxi-Chitimacha tribe, has lost 98% of its land, forcing residents out for safety. In 2018, the US government recognized this issue and offered assistance in relocating from their island, making them the first climate refugees.

Although they received land close to nearby Houma to protect life, their way of life is beginning to change as many are forced to get jobs that no longer use water, losing touch with their old way of life and each other as they move.

Other area tribes, like the United Houma Nations, have struggled with the movement of their people and the fight to retain their culture.

“A lot of our elders had to move away from where they grew up along the Bayou,” Duplantis says. “When you have to relocate to a place that you’re unfamiliar with, you lose a touch of culture.”

LaFleur warns that although the culture is not yet lost, it is a worrisome trend.

“It’s never too late to fix it up,” he says. “But we are worried about the culture being preserved in those towns.”