Clyde // Electricity at Yale University

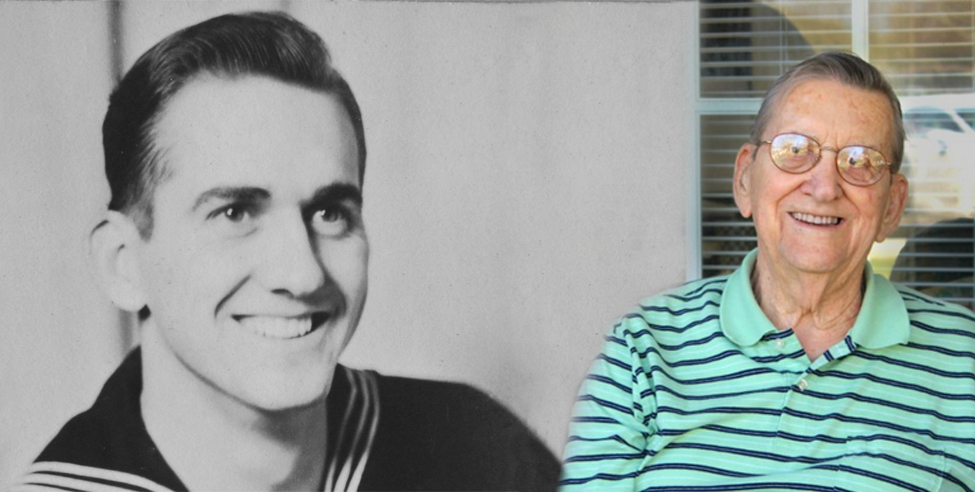

by Tanika Burlingame, Public Relations Director/Features Editor Electricity was in Clyde Naquin’s blood. His dad was an electrician. His dad’s dad was an electrician. It was a family legacy. So when he joined the Army Air Force in his early 20s, he was sent to teach cadets at Yale University how to make metal vacuums for recording devices — only armed with a high school diploma and a childhood surrounded by his father and grandfather’s work. Naquin was born in Thibodaux in 1918 and attended Thibodaux Elementary and Thibodaux High School. After high school he met and married the love of his life, Odette Cannicinne. The couple were married for 67 years and had five children, three boys and two girls. And when war broke out, Clyde signed up. At first he had no idea he would be teaching . . . It was not until he arrived at the Yale that his commanding officer explained that he would be teaching 10 flying cadets for 10 days on how to make metal vacuum tubes for recorders like the German army had been doing. The tubes the Americans were using at the time were glass and more susceptible to breaking. Naquin had more than enough experience as an electrician to be able to quickly teach the cadets the new process of how to manufacture the metal tubes and was given the data the Germans had been using by his officer. Naquin said classes started very early in the mornings and they would continue until dinner time. He would spend most of the morning going over the wiring system of the electrical process. Naquin admits he felt a bit insecure in his ability to perform calculus, which was needed for several of the formulas that he was teaching. “Within a matter of days, I knew I was teaching a group of smart individuals and I asked my students to help me better understand calculus. It was essential for what we were doing.” The young men agreed to help as long as he would promise to spend more time after hours teaching them how to make metal tubes. He said “they wanted to learn as much as they could as quickly as possible.” The cadets received a badge after each training course they completed and Naquin said he knew the cadets wanted the extra hours of help so they could receive their badges more quickly and complete their training faster. Naquin and his students quickly got to work and after lights out they would teach each other while holding flashlights under their sheets. He continued to teach the cadets the formula for making metal vacuum tubes and they continued to help him with calculus. This continued for several days until one night they were caught by his colonel. The next morning the colonel took Naquin in the office and told him to pack his bags. “I was certain once my colonel told me to pack my bags that I was being kicked out of the Army Air Force and sent home.” After packing, he returned to his colonel’s office, where he was informed that he was going to be attending officer training and in 90 short days he would be promoted to a 2nd lieutenant. And while being promoted to 2nd lieutenant was a great memory, one of his favorite memories was walking to the mess hall on Yale’s campus soon after he arrived and hearing a radio loudly playing Glenn Miller’s “Little Brown Jug.” It wasn’t until he got closer that he realized what he was hearing was a live concert. “To see a live concert by Glenn Miller, surprised me almost as much as being promoted to an officer after I had been caught breaking the rules.” Listen to some of Glenn Miller’s most popular songs: Naquin in uniform when he first entered the Army Air Force. Naquin in his Army Air Force uniform on his first mission in Wisconsin. Naquin in his 40s when he was established in his career as an electrician. Naquin dressed for a Mardi Gras ball in Thibodaux. Naquin shortly before he retired as an electrician. Naquin recalling the first time he met his wife Odette during a student interview. Photo by: Britney Fournier Naquin at the age of 96 during our first interview at Saint Joseph Manor.Photo by: Britney Fournier Tanika Burlingame, features editor, interviewing Clyde.Photo by: Britney Fournier Previous Next

What does Chu-Chut mean?

By Torri Sepulvado, Special Sections Editor What it is??? A Chu-Chut is a thing. What thing you might wonder? It’s anything you want it to be. A Chu-Chut is the thing that you can’t remember the name of in the middle of a conversation. It is a southern Louisiana saying that, as a transplant, I have come to love. It’s one of my favorite new words and I think it needs to be spread to the rest of the country. It keeps the conversation flowing, and somehow everyone knows what you’re talking about even though you never said. Let me give you an example: Girl: “Today I taught my nephew how to tie his shoes.” Friend: “How old is he?” Girl: “He’s 6, but you know that chu-chut on the end of the laces?” Friend: “Oh yea! The little plastic thing.” Girl: “Yes! That thing.” When the “chu-chut” came into use I don’t know, but whoever came up with it I want to shake their hand. I think it is such a clever word.

“Pops” // A Life of Love and Flight

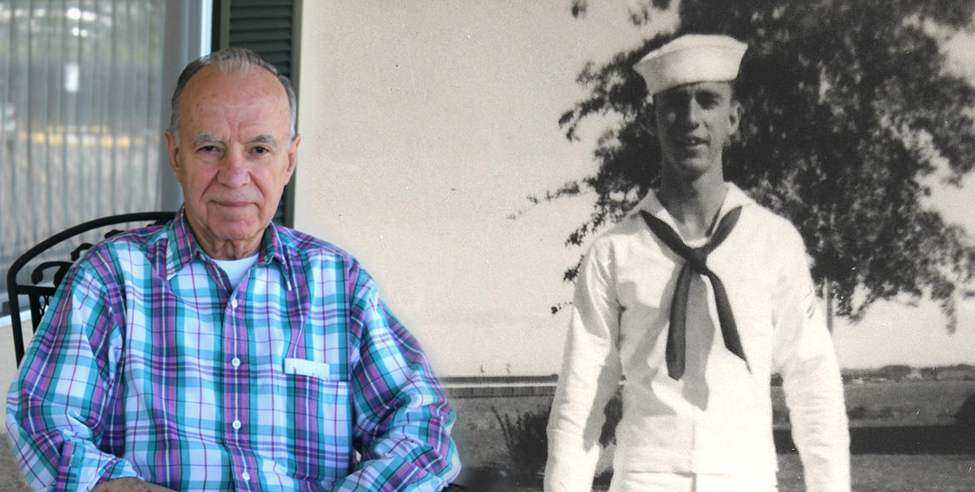

by Heidi Ohmer, Web Editor Ferol M. Langlois introduced himself with a firm handshake. “Call me Pops. If you ask for me by my first name, no one will know who you’re asking for.” Pops was born March 15, 1923, in Kenner, Louisiana, but moved to Destrehan when he was five years old. His house was provided by his father’s employer — an oil company — and cost $15 a month. And even though he grew up in the Great Depression, his dad owned a Model-T sedan. “Considering how everyone else was doing, my family always had what we needed.” The kitchen in the house had large wooden vats where his mother kept red beans, white beans, rice, and potatoes they bought by the sack. But the best part were the “shenanigans” with his three siblings. Just typical Southern kids playing games outside, pulling pranks, being competitive in Boy Scouts, and swimming in City Park’s swimming pool. And then he met his wife. “She was 13 and I was 15. You know, she was the only woman I have ever been with in any shape and form, and she is the only woman I will ever be with. We did and went everywhere together, and I have the utmost respect for her.” Pops went to Destrehan High School where he was in Boy Scouts and played multiple instruments in the school band. One of his proudest moments was achieving Eagle Scout in the Boy Scouts. And then the world changed. “We were in Braithwaite playing football—it was a state championship game—and that’s when Pearl Harbor happened. They stopped the game and made the announcement on the PA system to us.” The war mostly changed the stuff of everyday life. Stuff like meat, shoes, tires, gas were rationed. Pops said gas stamps had ratings. He received a “C rating” later on because he was in the service, which meant he received more gas than the other ratings. The nation came together to support the troops by not only rationing, he said, but also the lady riveters who stepped up to work. He graduated from high school in 1942 and then volunteered for the Navy where he was trained to be a pilot. He went to Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana, for the V-5 program for aviation. The program had about 200 “boys” and the program lasted for 90 days. He traveled to many different places learning things like how to fly and land and navigation. His last stop was Pensacola, Florida, where he flew military planes. Pops had two or three weeks of flight school left until he got his wings. And then his military career suddenly ended. “We were in the pool — I loved to swim — and we were playing water polo. I was underwater with the ball and a guy stepped on my head. I lost hearing in my left ear.” The military had about $30,000 into his training and the academy was trying to keep him in the service. After being hospitalized for 90 days, he was sent to Chicago where he attended another school to study how to repair the equipment that he was already trained on. He was assigned to Corpus Christi, Texas, after he completed his schooling. After the war, Pops married his childhood sweetheart, Gertie, with whom he had six children. He went to Delgado in New Orleans for refrigeration repairs and eventually ended up at Firestone in Baton Rouge. He then got an opportunity to move to Thibodaux where he worked for Firestone for 23 years until his retirement. And yet, after so many experiences . . . it’s his wife that mattered most. “I lost her on my birthday. I didn’t celebrate my birthday for a couple years, but then I realized something. She has it better than me, she is up in heaven while I’m still on this earth, and one day I will see her again.” Pops graduated high school in 1942 then volunteered for the Navy shortly after. Pops (right) played alto sax, clarinet, and flute in high school. Pops frequently met at the swimming pool in City Park. Here he is wearing typical swimwear when he was growing up. Pops was the youngest of four children. He had two brothers, LeRoy and Dub (Wilbert), and one sister named Shirley who is shown here holding a baby doll. Pops in high school around 1941. Pops with his wife Gertie. They met as children, and married in 1945.

Hiram // Hard Work Makes the News

by Harmony Hamilton, Managing Editor Life could be hard in the 1930s and 1940s. One of five children raised by a single mother, Hiram Torres didn’t always have things come easily, so that just meant he worked harder. He worked hard at being a paper boy and then in circulation and all the way up to a newspaper vice president. Torres was born a twin on October 18, 1930. He grew up with four other siblings in a shotgun house in Algiers, Louisiana. His father died when he was only five years old and his mother supported the family by playing piano for silent movies and cleaning houses. He and his siblings would gather to sing around the piano with his mother. “We would gather in the front room of our shotgun house. One time, she picked out a song for me to sing called Last Night on the Back Porch (I Loved Her Most of All).” Hiram attended grammar school at Swartz School in on the West Bank of New Orleans. Since his mother was parenting five children alone, Hiram says they only wore shoes when school was in session since they had to walk there every day. If their shoes got a hole, they would have to put a piece of cardboard in the bottom of them. He delivered newspapers as a teenager and, instead of being called paperboys, they were called carriers. Sadly for Hiram, his bike was stolen during his route one day, landing him as a story in the very papers he threw daily. Hiram eventually earned enough money to buy a new bicycle. In addition to this job, Torres also built a shoeshine box. He said he would ride the Algiers Ferry and charge ten cents to shine the passengers’ shoes. Overall, Hiram says his childhood was good with many fond memories. He remembers days when he and his close friends could walk the streets when drugs, violence, and other modern issues were not a problem. But some big events leave an impression. When he was 11, Hiram remembers President Roosevelt’s speech after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He was playing at a friend’s house on December 7, 1941, on the West Bank of New Orleans, Louisiana, when news quickly spread of the bombing. He and his friend ran inside to hear Roosevelt’s historic speech. During Hiram’s youth, segregation and Civil Rights was a pressing issue; however, he was not affected by the racial antics surrounding him. He lived across the street from a mixed neighborhood and was friendly to local African-American kids. In school, Hiram says the racial barrier was not that strong and that the adults were the ones deeply rooted in the segregation. Hiram joined the Navy in 1951 because he did not want to be drafted into the army and remained in service until 1955. He married his wife Joyce in his uniform in 1952. The two met when they were teenagers and Hiram remembers walking Joyce home after her shift had ended at the local drug store. Together, they had five children. One of their children, Gregory, is currently in his twenty-fourth year as the director of bands at Nicholls State University in Thibodaux. Before and during his time as a Navy man, Torres found himself back in the newspaper industry. In 1948 he started working for The Times-Picayune. He began working in the circulation department, then was transferred to the credit department and then was promoted to vice president. He spent 48 years at The Times-Picayune, retiring in 1996. Torres says his boss asked him why he did not stay for 50 years. “Forty-eight is enough.” Hiram’s high school senior portrait. Hiram (left) and his twin Brother Harold, each weighing 9 pounds at birth. Hiram riding a horse at 7 years old. Hiram (left) and brother Harold at their 1st communion. Hiram delivered newspapers as a teenager, but unfortunately his bike was stolen. Here is a Paper excerpt telling the story. Sitting in City Park in the late 1940s. Hiram joined the Navy in 1951. Here he is on shipping day. To: Mom “Ha! Chuck that Pose. The bay is in the rear. Bay separates Portsmouth from Norfolk, VA. Almost 1951. Love as always, your son Hiram.” Hiram married Joyce in 1951. Love letter written on back: “Baby, Wish I’d have know that the wind had blown my neckerchief crooked. I look like a sloppy sailor. Darling, I can hardly wait for the 8th to come. Love as always, Hiram” Around 1954 Young Hiram holding one of his children. He and his wife Joyce had 5 children. Hiram’s Times-Picayune staff photo. He worked at the New Orleans’ newspaper for 48 years. Photo by: Britney Fournier Previous Next Check out what news the New Orleans Times-Picayune is covering today: