Bienvenue én Louisiane.

By Payton Suire Bienvenue én Louisiane. The beautiful state of Louisiana is the Sportsman’s Paradise, and as residents, we want our paradise to last for generations on. The Sportsman’s Paradise experience isn’t so scenic when the Louisiana estuaries and habitats are covered in cigarette butts, plastics, cans, tires, etc. Litter doesn’t just make Louisiana or […]

The Nicholls Farm

By Robbie Trosclair The Nicholls Farm, started in 2006, has since become a project to grow wildlife that is necessary for the protection of our coasts. Following my recent podcast with Quenton Fontenot, Professor and Head of Biological Sciences, I also got the chance to sit down with Keith Chenier. He’s a 5th year Marine […]

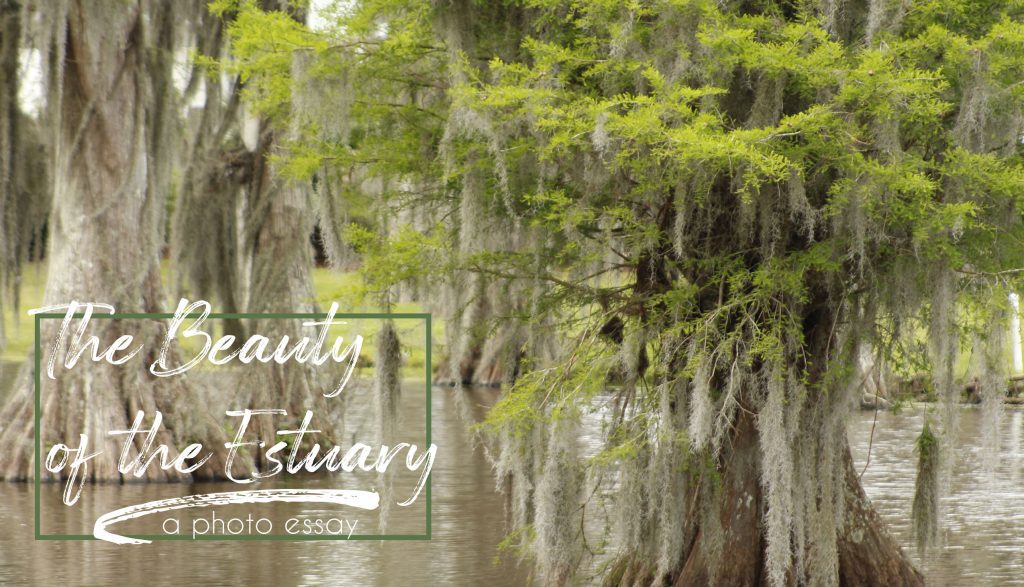

Beauty of The Estuary

Previous Next

Welcome by Professor Nicki Boudreaux

“On average, Louisiana loses a football field of land per hour.” We’ve all heard that statistic time and time again in reference to land lost to coastal erosion, sea level rise and other factors. The first time I heard it was in the late 1990s, and my passion for all things Coastal Louisiana was born. […]