Recreating the Circuit: Stark Field

jaci remondet staff

Odd Fellows Hall

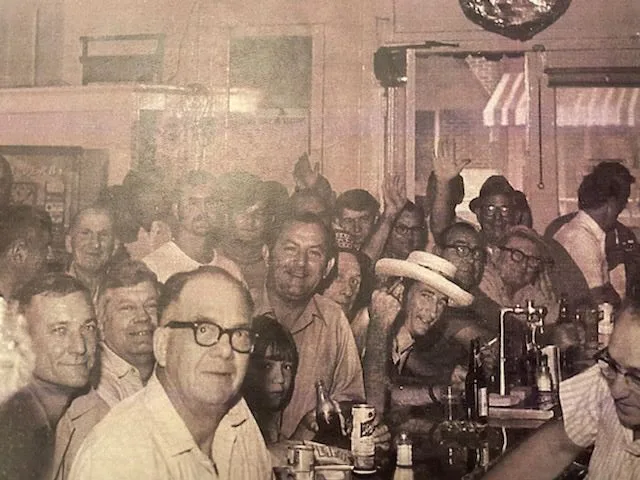

skylar neal staff Fifteen miles south of Thibodaux, the Odd Fellows Hall in Houma echoed with the dynamic performances of Chitlin’ Circuit artists through the night. In the 1930s-1970s, Guitar Slim, Joe Tex and Ike and Tina Turner performed in Houma, Louisiana, at the Odd Fellows Hall, a venue along the Chitlin’ Circuit. Located at 915 Canal Street, The Odd Fellows hall stood between two historic bars: The 45 on the right and Sanko’s on the left. Part of the Odd Fellows Hall building still stands today between Vida Paint & Supply Inc. and The Eye Club. The hall was located in Houma’s “red-light district,” an area where many Blacks lived. The area, known as the “Back of Town,” extended from Canal Street to Grinage Street. Just as other Chitlin’ Circuit venues had managers, Houma’s manager was Irvin Picou. Picou signed band contracts and scheduled performances for the hall. In addition to being the Hall manager, he worked as a porter at various locations in Houma, including on a train that ran through Shriever’s railroad. Alma Scott, a former resident of the Odd Fellows Hall, remembers living there and seeing Ike and Tina Turner, Guitar Slim and other artists perform. Scott says the Odd Fellows Hall was a two-story building with ten rooms on the first floor where people and performers could live or stay and a dance hall on the top floor where performers could play. To the building’s left was a porch with stairs leading to the dance hall. Scott and the other children could not enter the hall when adults were present because of the presence of alcoholic beverages. Instead, they would watch from outside. “We could go up the back steps, and there was a big fan that was there that would cool the place off, and we could look through the fan and into the door, and oh boy, it was wonderful,” says Scott. Houma resident Martha Turner remembers the Odd Fellows Hall from her childhood in Houma, though she was too young to enter the hall at the time. “When any groups or celebrities came in [to Houma], it was always held at the Odd Fellows Hall, because that was the biggest place in Houma that you could have anything like that,” she says. Alvin Tillman, a local Houma Chitlin’ Circuit historian, says Houma was a happening place. “That particular area of Lafayette Street, and the Barataria – Canal Street area where the Odd Fellows hall was located, it was like our Bourbon Street. Just about anything you can think of was found in that particular area.” Alvin Tillman Like Bourbon Street, Houma’s Canal Street thrived with activity, and The Odd Fellows Hall was the heart of it all. Canal St. in Houma which was the location of Odd Fellows Hall from the 1930s to 1970s These are the remains of what was the Odd Fellow Hall Landmark of Downtown Houma The street view of the Odd Fellows Hall (left), The 45’s Apartment Building (middle) and The 45 bar (right) Was The 45 bar on Canal Street The Space Between what’s left of Odd Fellows Hall and The 45 Bar Apartment Building

The Rose Club

kaylie st. pierre staff The grand opening of The Rose Club in the 1950s was the beginning of years of dancing, music and memories for the South Louisiana residents of Verdunville. The Rose Club was a dance hall that welcomed many talented Black artists, starting during the grand opening with Hosea Hill’s Serenaders. The Serenaders were a house band of The Sugar Bowl, a popular bar on the Chitlin’ Circuit in Thibodaux near Verdunville. The owner of The Sugar Bowl, Hosea Hill, started the band. Rose and Curtis Martin originally owned the club, located at the intersection of Highway 182 and Prairie Road. Originally a store and gas station in the 1930s, it became the Rose Club in the 1950s. Their grandson Billy Martin has fond childhood memories of the club. “In the ’50s, Popsi bricked it and redone inside,” says Billy Martin. “It was awesome as a little kid to go inside. I stayed on the pinball machines.” This venue offered dining and dancing every night, except Mondays from 6 p.m. to midnight. The menu had a variety of items from steaks and fried chicken to seafood. A highlight was live music on Saturdays and air conditioning. The Rose Club hosted a variety of orchestras and bands. Thomas Lyons, a Thibodaux resident, always had a love for music. In 1972, he discovered a local Black zydeco artist named Clifton Chenier. Years later, Lyons got word of Clifton performing with his brother, Cleveland at The Rose Club. He took a trip to Verdunville for Chenier. “I had this transcendent experience because Clifton Chenier was playing,” Lyons says. “I am fixated on Cleveland playing the washboard to this day.” Rose Martin, great-granddaughter of Rose and Curtis, says her family’s venue inspires her. “I’ve heard many beautiful stories about the club — how fated relationships were created there; family outings were spent there and nothing but good times were a big hit at the club.” Rose Martin In 1981, a fire destroyed The Rose Club. Although the venue is no longer, its memory remains. Rose Martin says, “I can only hope that one day our little community can have something like that again.” Photos courtesy of Rose Martin A ticket to The Rose Club Grand Opening night when Hosea Hill’s Serenaders opened The Rose Club as a Dance Club. The Rose Club after it was redone as a club. The Rose Filling Station in 1933 as a gas station, before it was the dance club called The Rose Club. The interior of The Rose Club The interior of The Rose Club. Billy Martin, whose grandparents Rose and Curtis Martin Sr owned the Rose Club, posing in front of the Rose Club before it was a dance hall. Rose Martin, the owner of The Rose Club, with her two daughters.

Teddy’s Juke Joint: Keep the Chitlin’ Circuit Alive

sally-anne torres staff

Breaking the Rules: Leroy Martin and the Sugar Bowl

gabrielle chaisson staff In a time when Jim Crow laws banned whites and Blacks from integrating, a white Golden Meadow native broke the rules for the love of music. Leroy Martin was born on Aug. 4, 1929, in Golden Meadow, Louisiana, and served as a Lafourche Parish assessor, a disc jockey for KTIB radio station in Thibodaux and a friend of Sugar Bowl owner Hosea Hill. As a child, Martin’s family moved to New Orleans for his father’s job, and during this time, he noticed the racist treatment of Black people, says his daughter Lisa Martin. “My dad lived in New Orleans for two years, and I remember him telling me that Black people had to sit in the back of the bus,” she says. “It was unreal to him… He wanted to tell them that they could sit with him.” He was a “historian by choice,” Lisa Martin says, so he wrote a weekly column for The Lafourche Gazette titled “In A Small Pond,” where he shared stories from his life. In one column posted on Oct. 28, 2015, Leroy Martin shares his experience visiting the exclusively Black Sugar Bowl club in Thibodaux, Louisiana. He and his station manager, Hal Benson, met with Hill and presented a plan to get into the club, according to his column. Martin recalls Hill saying the plan “broke no law, just bent them a little.” “Hosea’s plan was to stack beer cases next to [a wall opening looking out from the kitchen to the stage], technically hiding and segregating us…and arrange holes into the stacks big enough to see and hear the bands…We were in the presence of greatness,” Martin wrote in the column. Martin saw artists like Lloyd Price, Tina Turner, Guitar Slim, Fats Domino and Allan Toussaint perform here before they became the big names of today, according to his column. Martin was always passionate about music and became a popular musician whose style contained elements of blues, jazz and Cajun music, says his daughter. He performed across Louisiana, Canada and even at the Grand Ole Opry. Martin also produced songs for other artists like Jimmy Donlay at Cosmos Studios in New Orleans, according to friend and local musician Tommy Lyons. Martin’s opposition to the racist laws and his love of music brought him into the club, according to his column. “Were we breaking the law? That law was later overturned and declared illegal by the Supreme Court, so, therefore, you cannot break an illegal law. Makes sense to me. That’s my story, and I’m sticking to it. BYE NOW!” Leroy Martin Although Leroy Martin died on Sept. 12, 2019, his column continues to shine a light on the Chitlin’ Circuit. Leroy Martin as a Child Leroy Martin on the Far Right Performing in a Band Leroy Martin at KTIB Radio Station Leroy Martin’s Column on The Sugar Bowl in The Lafourche Gazette

The Sugar Bowl

sarah kraemer features editor Every Saturday night, the Sugar Bowl’s walls reverberated with the sound of the blues and R&B. The club was a safe space where the community would gather for entertainment and support when needed. The club was known for its Cajun food and live music. It was one of the most popular hotspots in Louisiana on the Chitlin’ Circuit. “It was part of Black culture. Saturday night they went out to listen to music, and in Thibodaux, it was the Sugar Bowl.” Jeff Hannusch Hanusch is a family friend of the venue’s owner, Hosea Hill, and his family. The Sugar Bowl started around 1932 as a bar in a rented building on Narrow Street. Thibodaux native Hill owned the bar, hoping to target people from his mother’s nearby cafe. Hannusch says the venue’s name came from its patrons, such as cane workers from the sugar mill about 10 minutes down the road called Lafourche Sugars. The sugar industry, which started over 200 years ago, is still bustling today. Lafourche Sugars produced 231 pounds of sugar in 2018, according to the American Sugarcane League. About 20 years later, Hill moved the Sugar Bowl to a larger, more permanent location at 915 Lagarde Street. The bigger venue included a dance hall “that could hold more people and attract larger artists,” says Hannusch. Tina Turner, “the Queen of Rock n’ Roll,” and Guitar Slim, a guitarist known for hits like “The Things I Used To Do,” are some of the many artists that played at the venue. Guitar Slim, a guitarist from Mississippi, would play with the bands as a house musician, says Hannusch. House musicians would sit in with bands who were missing musicians during their time at the venue. They performed R&B, Blues and Rock n’ Roll music at the Sugar Bowl as they couldn’t play in mainstream white venues because of the segregation laws. “The cops would always hassle them. Hill would have to pay the cops off at times.” Hannusch says. “There used to be a problem back in the day when white people went to black clubs [and vice versa].” But that did not stop white people from coming to the Sugar Bowl. Hannusch says during segregation there were risks of getting arrested. But, he says Hill would let those white people in so long as they paid their admission fee. The payment and risk factors were the least of Hill’s concerns because he focused more on creating a positive space for musicians and the community. “He helped a lot of musicians out,” says Hannusch. “He bailed a lot of bands out that got stranded. He put them out for free until they could get on their feet.” Hill helped the community through the Sugar Bowl, too, according to his niece. “Resources were very limited on the Chitlin Circuit,” says Hill’s niece Angela Watkins. “Fortunately for us, Uncle Hosea was the guy at the right place and the right time to be able to help people furthering their careers, help with raising children, and help with feeding the community.” The venue burned down around 1969, but the community helped him to build the club back in close to 30 days, says Hill’s grandson Harvey Hill. “The community really supported the club,” he says. “The fire marshall, police chief and people of the community helped to build it back.” Hosea died in 1973 from cancer, and the club closed shortly after. “There’s no Chitlin’ Circuit [or Sugar Bowl] anymore, but if [people] listen to the music of the era [they can] get an appreciation for what it was like.” Jeff Hannusch Sugar Bowl in the 1930’s Hosea Hill’s Sugar Bowl Newspaper about Sugar Bowl Hosea Hill, Thurston, Harvey SR Sugar Bowl Location Today Sugar Bowl Location Today 915 Lagarde St. Closeup Front of 915 Lagarde St.

Recreating the Circuit: The Sugar Bowl

jaci remondet staff

Chitlin’ Circuit’s Start in the Bayou Region

sally-anne torres staff In the mid-1900s, music could be heard throughout the Bayou Region of South Louisiana when the sun set. Playing through the night, blues, rock, jazz and soul harmonized with the late-night laughter of African American artists who established venues for performers since they were not allowed in white spaces. Frank Painai owned a barbershop-turned-hotel on LaSalle Street in New Orleans, where musicians like Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, and Irma Thomas played inside. During the 1930s, Painai decided to expand and build a bar and hotel inside the shop. The inn was more than just a place to watch performers and sleep. The inn acted as an incubator for the start of Rock ‘n’ Roll, according to the Dew Drop’s website. Artists would often travel through the night to the next venue, trying to stay out of the police’s eye. “It’s almost like another form of the Underground Railroad. They had ways to move around to evade running into the law. Many times they [Black musicians] were targeted.” Margie Scoby, founder of the Finding our Roots African American History Museum in Houma Painai and Hosea Hill, an entrepreneur from Thibodaux, made good friends and even better business partners. When the musicians finished at the inn, Hill would take artists from there and bring them an hour southwest to the Sugar Bowl in Thibodaux, also known as Hosea’s Place, says Angela Watkins, Hill’s niece. Watkins recalls the Sugar Bowl as being the most popular club in Thibodaux. “There was always entertainment at Uncle Hosea’s Place. His place was the most popular,” says Watkins, “When they [musicians] came through the Dew Drop Inn in New Orleans, the next stop was the Sugar Bowl.” The business owner and entrepreneur also hired the Hosea Hill Serenaders, the Sugar Bowl’s house band, to play during the week when no big acts were in town. When big names performed, like Tina Turner, Guitar Slim and Fats Domino, teens could be found spread around the club’s perimeter, hoping to catch a glimpse of the show. “When artists would come close to Thibodaux, like New Orleans, Hill arranged for them to pass through Thibodaux as well,” says Patrick Bell, pastor at Allen Chapel AME in Thibodaux. Hosea would book out Stark Field, then a baseball field and now the police station on Canal Boulevard in Thibodaux, for bigger shows like Lloyd Price or James Brown. Gigs like these were Thibodaux’s first integrated events. “He could put on concerts at Stark Field, rent it, and fill it,” says Denis Gaubert, a local historian and former lawyer in Thibodaux. Odd Fellows Hall, the Rose Club and the Hawaiian Lounge could be found 15 miles down the bayou in Houma. “It [Odd Fellows Hall and the Hawaiian Lounge] was a stomping ground,” says Scoby. Scoby says the venues along the circuit served as a safe space for the African American community to gather and have fun. Bell says, “It [Chitlin’ Circuit] was the inspiration for a lot of people from Thibodaux that got into the performing arts business, particularly music.” Bayou Lafourche Dark Bayou Lafourche Dew Drop Audience Dew Drop Cafe Dew Drop Cafe Flyer Dew Drop Inn Today Safari Room Nola Tony’s Cafe, New Orleans, Louisiana Tina Turner performing at Dew Drop Cafe