The Spiritual Backdrop: Thibodaux Churches

treneice cannon video editor

Setting the Stage for the Chitlin’ Circuit: Thibodaux History and Culture

Hannah Robert and Jennifer Marts podcast editor & staff Thibodaux, Louisiana, formed as a trading post between New Orleans and Bayou Teche in the late 1700s. This area, rich in cultural traditions, was a melting pot of races and nationalities. It was this mix of African, French, Spanish and Creole cultures that made South Louisiana […]

The Great Depression and WWII’s Impact on The Chitlin’ Circuit

kaylie st.pierre staff On a Saturday night in South Louisiana, sounds of saxophones, laughter and dancing filled the air, regardless of the tough times and uncertain future. The local nightclubs offered the only entertainment around, promising memories and good music for just fifty cents. The Chitlin’ Circuit thrived during the Great Depression, from 1929 to […]

Podcast Series: Community Memories

jaci remondet staff Jerry Jones former Lafourche Parish Councilman Thomas Lyons raised in Houma and moved to Thibodaux for college Harvey Hill Chitlin’ Circuit venue owner Hosea Hill’s grandson

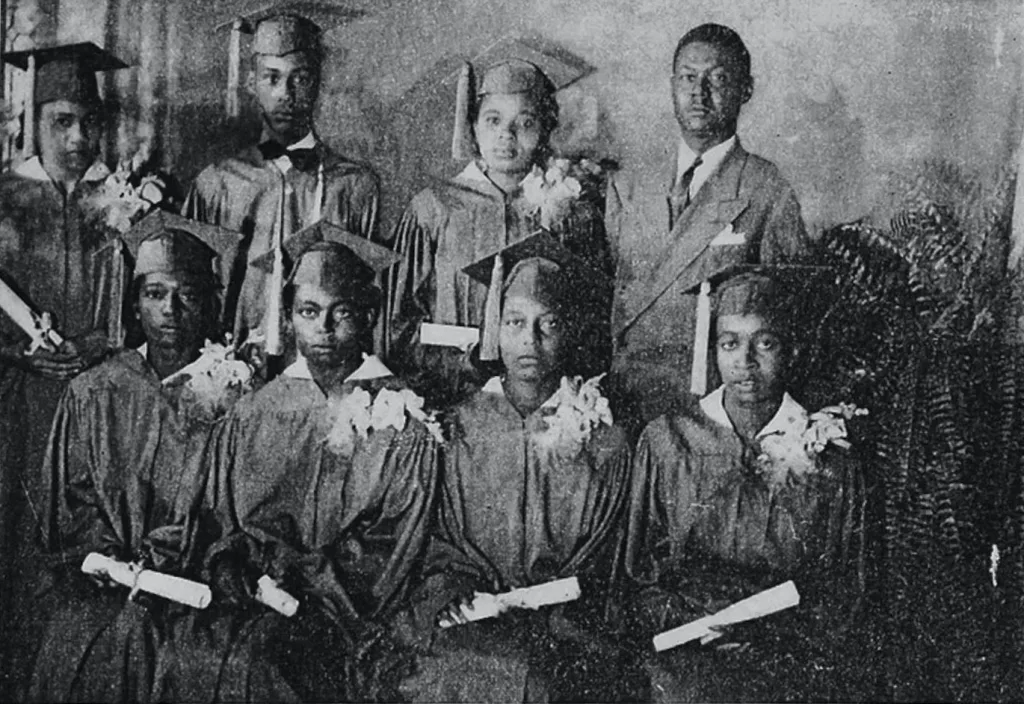

C.M. Washington: Educating the Community

jennifer marts staff In 1902, a Black woman named Cordelia Matthews Washington pioneered the Negro Corporation Training School in “back of town” Thibodaux, Louisiana. African American children traveled lengthy distances from Cut Off to Houma and even Napoleonville to attend this all-Black school. “I had to make a round trip of 70 miles a day, […]

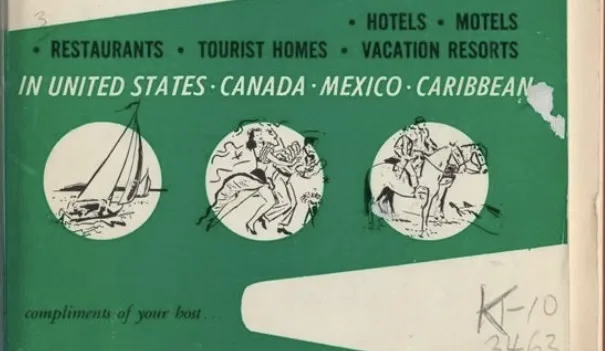

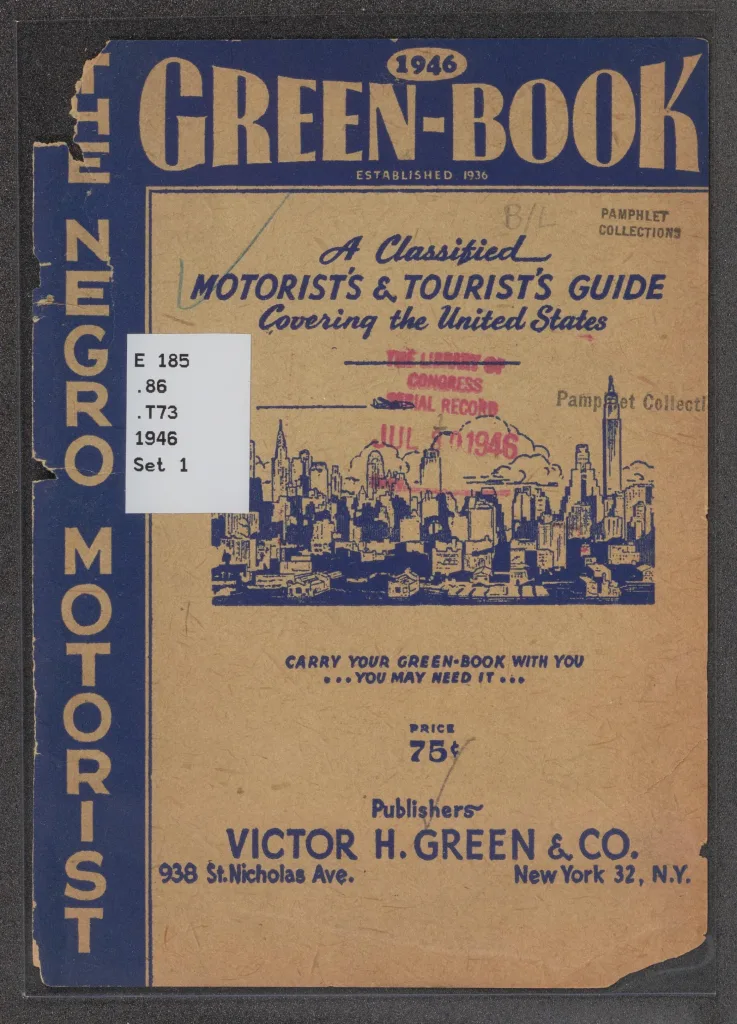

A Traveling Guide: The Green Book

skylar neal staff Other Green Book Travel Guides During Segregation

The Secret Code of the Chitlin’ Circuit

sally-anne torres staff During segregation, Blacks came up with ways to tell each other where to go so they could be safe and enjoy activities. The “Chitlin’ Code” represents how they knew what venues to visit or where to perform. The world of Black music existed separately from the entertainment nearly everyone listened to at […]

An Overlooked Artifact: Moses, Allen Chapel, Calvary Cemeteries

gabrielle chaissson staff Hidden among Thibodaux, Louisiana’s side streets lies a cemetery with a deep connection to the Chitlin’ Circuit. Hosea Hill and Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones, two significant circuit figures, are buried in Moses, Allen Chapel, Calvary Cemeteries. Hill owned the Sugar Bowl—a venue that brought the circuit down to Thibodaux—and he managed “Guitar […]

How the Circuit Got Its Name

jaci remondet staff A distinct smell travels through the air as water starts to boil over the hot stove fire. The oil hisses as the holy trinity — onion, green bell pepper and celery — sauté together. Chitterlings are on the menu for dinner tonight. Chitterlings, sometimes spelled chitlins or chittlins, can be prepared in […]