U-boat POWs

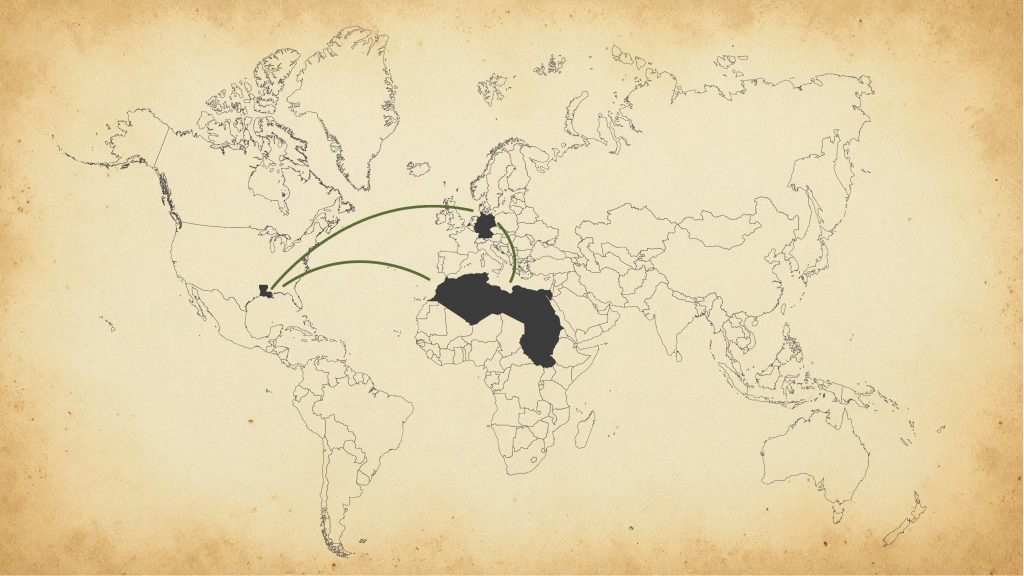

aynsley andras staff writer German U-boats (submarines) targeted merchant vessels in the Gulf of Mexico in an effort to disrupt the Allies’ supply lines. This campaign had a significant impact on Louisiana’s coast and the prisoners of war captured from the U-boats. The U-boats specifically targeted defenseless tankers and transport ships to cut American oil supply lines through the Gulf, according to When German Submarines Brought WWII to Louisiana’s Shores by Eli A. Haddow. This was due to the Gulf having access to the Mississippi River and merchant ships passing through. One of the most well-known U-boats to be captured and the crew sent to Louisiana was U-505. U-505 was seized on June 4, 1944, as it was returning home after patrolling the Golden Coast of Africa, according to The U-505, a Submarine from Hilter’s Deadly Feet, is Captured. Brian Davis, the executive director of the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation, says the U-boat crew was sent to Camp Ruston, located seven miles northeast of Ruston, Louisiana. “The crew was sent there because it was such a remote area,” he says. “They [prisoners] were less likely to have a direct route to be able to find their way back to U-boats.” The U.S.S. Task Force Guadalcanal captures the German submarine U-505. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Portrait of the U-505 German submarine, which was boarded and captured at sea, and the first foreign man-o-war captured by the U.S. Navy since 1815. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Crew of the U-505 before being captured by the U.S.S. Guadalcanal. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. A U-boat crew cramped in the sleeping quarters. Clay Blair Collection- American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming A U-boat crew that was captured and sent to a POW camp in Louisiana. Photo Credit: C.J. Christ A U.S. merchant ship sinking after being attacked by U-boats in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo Credit: National WWII Museum In New Orleans A map of U-boat tracking in the Gulf between 1942-1943. Photo Credit: Houma National WWII Museum

Life for German POWs Leaving America

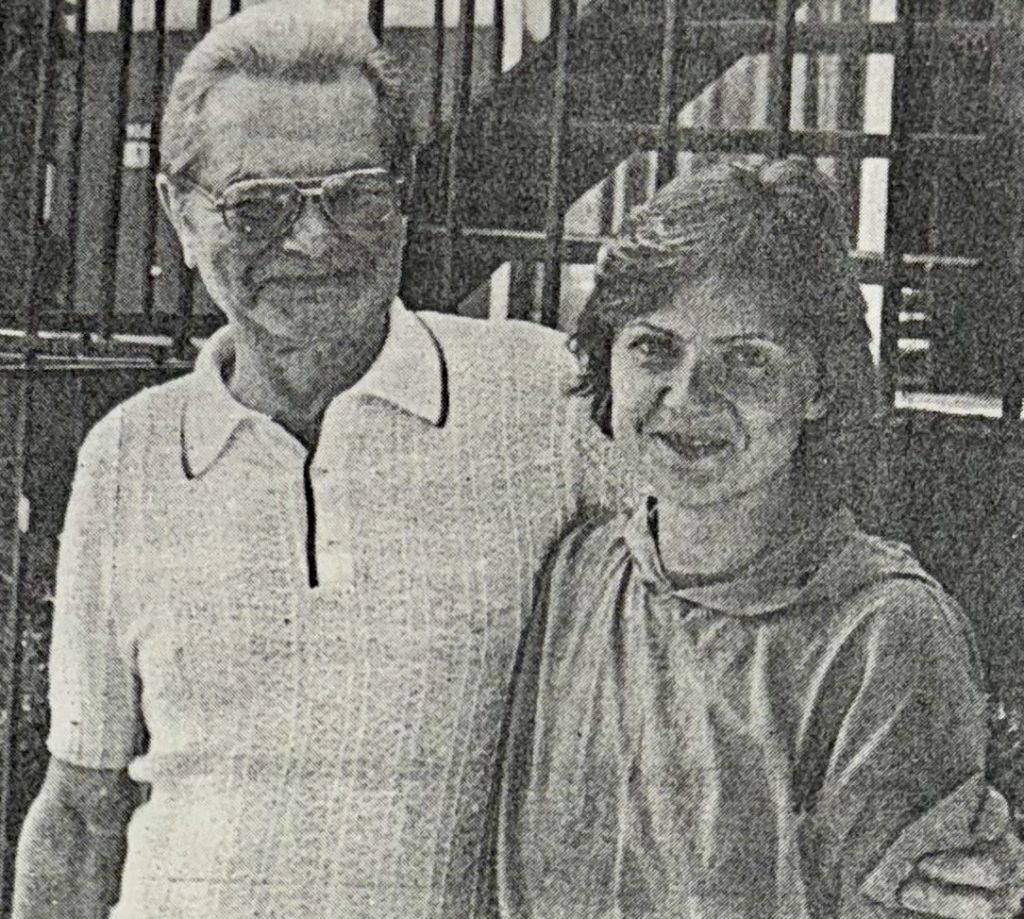

madison blanchard staff writer The war was over in 1945, but for thousands of German POWs, the journey home was put on hold. Instead of going home, they helped rebuild the countries their army had torn apart. Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, POWs were not allowed to stay in captivity as they were to be sent home. However, many POWs were held for months or even years after World War II, continuing to work despite the war’s end. About one percent of German POWs remained in the United States, and a larger percentage returned later due to poor employment prospects in post-war Germany, according to an article from HistoryNet. “Many of them [German POWs] wanted to come back to America,” says Kurt Stiegler, an assistant professor of history at Nicholls State University. According to German estimates, 5,000 Germans did come back to America. When they did an exit poll of the German POWs, 74% of them had favorable opinions about America.” “Many of them [German POWs] wanted to come back to America . . . 74% of them had favorable opinions about America.”” Kurt Stiegler Although German POWs could not remain in the United States after the war because of diplomatic issues, many wanted to return and took the necessary steps to re-enter the country and become citizens. In the early 1990s, nearly 47 years after World War II ended, the Thibodaux Daily Comet published an article featuring former German POW Gerhard Hoelling’s return visit to Camp Thibodaux. Hoelling, a retired electrician from Bremen, Germany, remembered Louisiana as a very interesting place, with its snakes, cane fields and lenient American soldiers. In this newspaper clipping, reporter Suzy Fleming quoted Hoelling as saying,“I came here with my daughter only to see one small Thibodaux, I was about six weeks in camps (in France) captured by Americans. Then to Great Britain only four days, then from Liverpool we needed nine days to come by ship to New York.” While being captured brought uncertainty and fear for prisoners of war held in the United States, the experience turned into one of opportunity and work for many. Some stayed in Germany after repatriation, while others chose to return to the United States and start a new life. Former German POW, Gerhard Hoelling and his daughter Sabine Giese visiting Thibodaux 47 years after he was released.

POWs and the Economy

aynsley andras staff writer Faced with a wartime labor shortage that threatened Louisiana’s sugarcane industry, they turned to prisoners of war to keep the crops, and the economy, growing. World War II led about 280,000 young men and women from Louisiana to help in the war, leaving a shortage of workers in local industries, says Glenn Falgoust, who researched the Donaldsonville POW camp. “They [U.S. Military] just left the territory for four years, so these sugarcane plantations were in trouble,” Falgoust says. “No labor. No labor, you can’t produce a crop.” “They [U.S. Military] just left the territory for four years, so these sugarcane plantations were in trouble. No labor. No labor, you can’t produce a crop.” Glenn Falgoust With that labor shortage, sugar prices rose. Eventually, the Office of Price Administration set a price ceiling on sugar and implemented rationing, according to Prisoner of War Labor in the Sugar Cane Fields of Lafourche Parish, Louisiana: 1943-1944 by Joseph T. Butler Jr. With labor in demand, the state decided to employ prisoners in the sugarcane fields. Prisoners worked six days a week starting their day at 4 a.m., says Falgoust. Prisoners who completed their assigned tasks ahead of time were allowed to return to their respective camps before the end of the work-day, while repeated failure to finish assignments resulted in disciplinary action according to Prisoner of War Labor in the Sugar Cane Fields of Lafourche Parish, Louisiana: 1943-1944. While the POWs worked in the sugarcane field, they were paid for their labor. The Sugar Act of 1937 established minimum wages for cane workers providing benefit payments to sugar planters and extended through the end of 1944, according to Prisoner of War Labor in the Sugar Cane Fields of Lafourche Parish, Louisiana: 1943-1944. The War Manpower Commission set the average daily wage for inexperienced free labor at 80 cents, while the maximum a prisoner could earn was $1.20. The prisoners were paid in canteen scripts, which the prisoners could use to buy items. “One of the things I found was a copy of a canteen script, which was the money you would use at the canteen paying for things,” says Brian Davis, executive director for the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation. Falgoust says the prisoners could buy paper, pencils, razor blades, soap, and non-alcoholic lotion with the canteen scripts. They were allowed to bring these things back into the camps. By placing POWs in Louisiana’s sugarcane fields under regulated conditions, the state was able to maintain a vital industry during a time of global conflict. German POW working in sugarcane fields at Camp Allen, Livingston, LA. Photo Credit: Joseph T. Butler Jr. German POWs in a cane field. Photo Credit: Everet Halbach POWs in front of a transportation vehicle. Photo Credit: Everet Halbach German POW loading into a transportation vehicle going back to camps. Photo Credit: Everet Halbach German POWs working in a cane field. Photo Credit: Evert Halbach Prisoners of war on work detail at local timber farms. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. An interview with John Lajaunie, finance professor at Nicholls State University, about POWs, the economy and war rationing.

POWS Path to Louisiana

Guards & Camp Workers

aynsley andras staff writer Inside the prisoner-of-war camps, a team of guards, workers, and overseers ensured the prisoners were well-supervised and cared for, with many duties extending beyond maintaining order. Many people worked inside the prisoner-of-war camps, from staff in the kitchen and dining hall to those providing medical services and guarding the prisoners. Tall wired fences, punctuated by guard towers, surrounded the entire camp, according to Kelly Ouhcley in POW Camps in Louisiana. Glen Falgoust, a journalist who researched the Donaldsonville POW camp, says, “Each one of these POWS probably had as many as 10 support people wrapped around them to be able to make sure they [prisoners] were properly taken care of.” “Each one of these POWS probably had as many as 10 support people wrapped around them to be able to make sure they [prisoners] were properly taken care of.” glenn falgoust The guards’ work continued even after the prisoners were sent to work in the fields. Everet Hallback’s father worked as a mechanic at one of the prisoner of war camps. “When he didn’t have anything to repair, he would take them and put the POWs in the flatbed truck and then transport them and kind of watch and see to make sure they all wouldn’t run away,” Hallback says. According to a column in the Houma Today by C.J. Christ, a designated area was made for the guards to sit where they could observe all the prisoners. Some American workers at the POW camps brought water to the prisoners on wagons while the prisoners worked at the sugarcane fields. The guards and workers still treated the prisoners with respect, says Linda Theriot, secretary at the Houma Military Regional Museum. “Prisoners here were well taken care of and the guards, not only the guards but the property owners, treated them good,” Theriot says. “Some did not want to go back home.” Laton Tudor, John Kalinoski, Barnes, Johnny Andrews, Charles Torrey, “Pop” Alvin Clary, and John Hoffman in front of Camp Ruston barracks. Photo Credit: Louisiana Tech University Military employees John Hoffman, Mike Harris, Mary Snelling, and Charles Torrey in front of Camp Ruston Headquarters. Photo Credit: Louisiana Tech University Portrait of seven female camp workers on the Camp Ruston grounds. Photo Credit: Louisiana Tech University Torrey, Andrews, Tuminello, Farmer, and Kalinoski standing in uniform at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: Louisiana Tech University Six mess hall employees sitting on the mess hall steps at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: Louisiana Tech University Portrait of Bill Sherer and Nancy Colvin standing in front of Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: Louisiana Tech University Orderly room for the US Army guards at the prisoner of war camp at Camp Polk, La. Photo Credit: Rickey Robertson Collection Mess Hall at Camp Polk German POW Camp with 2 German POWs pictured. Photo Credit: Rickey Robertson Collection

Camp Activities

aynsley andras staff writer Prisoners of war engaged in a variety of recreational and creative activities during their time in captivity. From playing soccer and card games to painting and woodworking, these activities offered the prisoners both physical and mental respite. For most of the day, the prisoners of war worked in fields and were occasionally allowed to enjoy recreational activities. Everet Hallback, whose father worked as a mechanic while the POW camps were in South Louisiana, says the prisoners enjoyed playing with the stray dogs while waiting for transportation back to the camps. And some liked to play various card games once they got back to the camps. Glenn Falgoust, a journalist who researched the Donaldsonville POW camps, says, “They played soccer, had a little sports field, and a dance hall.” “They played soccer, had a little sports field, and a dance hall.” Glenn falgoust In addition, some prisoners painted. Linda Theriot, an executive at The Houma Regional Military Museum, says a Houma camp prisoner, Otto Webber, painted multiple paintings, including a self portrait with his son. Some prisoners were interested in woodworking and masonry. “Sometimes there were training walls, like along a ditch or steps up to a house or up a hill,” says Brian Davis, executive director for the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation, about the Ruston camp. “Some of them were laid out by prisoners who would do work details out in the community at the time as well.” However, not all activities were physical like playing sports. Some of the activities were there to help the prisoners spiritually or mentally. A few camps allowed Catholic Mass for prisoners. In addition, Theriot says some prisoners may have been taught by teachers employed by their employer’s families — like the Matherne family who employed POWs from one of the Houma camps. The Thibodaux camp’s POW soccer team. Photo Credit: Nicholls Archives Italian POWs attending mass in New Orleans. Alvin Pop Clary and William Bill Bernsten, in a Camp Ruston baseball uniform, at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: Louisiana Tech University Camp Ruston Collection Houma POW Portrait Artist: Otto Weber An interview with Dan Davis about the portrait of his mother Portrait of Peggy Toups painted by German POW Otto Weber in 1944 at the Houma camp. Photo Credit: The Regional Military Museum Art at the Camps A painting from a photo by Otto Weber who was a German POW in the Houma camp. Photo Credit: The Regional Military Museum A drawing of German P.O.W. Camp Como done by Puelli at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection Sketch drawn by a German POW of the PeeWee Falcon House in Donaldsonville. Photo Credit: Glenn Falgoust A model with “Gott Mit Uns” on it, made by German prisoners of war at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Drawing made by Prisoners of war interned at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Drawing of a destroyer done by a prisoner of war interned at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Drawing of a horse and sleigh done by a prisoner of war interned at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Drawing of a Mercedes Benz done by a prisoner of war interned at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection Drawing of a ship at sea by a prisoner of war interned at WWII P.O.W. Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. German P.O.W. constructed replica of the Rhine Castle. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Model castle made by the P.O.W.s at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Photograph of an Amphitheater constructed by German prisoners of war at Camp Ruston. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection.

Eating at Camp

kade bergeron features editor During World War II, over 2,000 prisoners of war were confined in Louisiana’s Bayou Region, where they faced unfamiliar climates, terrain, and conditions. Yet, one aspect of normalcy remained — their food. Camps had dining halls, sometimes called “mess halls,” that were primarily used for dining and communicating. These spaces served as a common area for all residents of the camps to gather, according to an article in the Mississippi History Now. “Food was not a complaint for the prisoners. In fact, most of the food was prepared by German cooks with ingredients furnished by the U.S. Army.” The U.S. government provided ingredients that aligned with the typical nutritional standards of the 1940s era. Protein, grains, and vegetables were staples of the diet, as were some occasional forms of dairy, such as milk for coffee and butter for bread, according to Mississippi History Now. Although these rations were supplied throughout the camps in the Bayou Region, they also were able to get local food from the locals. “[Plantation owners] would take [prisoners] to their houses and feed them and treat them with some sweets, which was a rarity back in those days as it was rationed,” says Linda Theriot, secretary at the Houma Regional Military Museum. “[Plantation owners] would take [prisoners] to their houses and feed them and treat them with some sweets, which was a rarity back in those days as it was rationed.” Linda Theriot Due to the war efforts, supplies were limited, so the government provided nutritional rations based on availability. The meals were of the same variety that the military received, according to Mississippi History Now. Depending on the camp location and the amenities associated with that camp, some prisoners of war received higher-quality ingredients compared to prisoners at other local camps. The late Dr. Guy R. Jones was the primary physician who was responsible for monitoring the health of German prisoners of war at the Lockport/Valentine POW Camp. Jones said the prisoners received meals that were much better quality than those of the local Lockport residents, according to an article published by the Louisiana Historical Association. The war efforts put a strain on residents obtaining goods, but for the POW camp residents, the supplies administered by the U.S. government eased this burden. Some say that the prisoners were better off in terms of food quality (and quantity) than citizens who were rationing to support the American troops, according to the Louisiana Historical Association. In addition, the prisoners’ contact and work for local industries gave them access to other foods. “Working the farmland probably gave prisoners [the ability] to earn food on top of [the] wages set by the U.S. government,” says April Cortez, North Thibodaux resident, and native of the POW camp area. “The food supplied to the camps was just the beginning… The prisoners got additional food from the locals and the landowners for their work.” Daily German P.O.W.s breakfasts consisted of cereal (corn flakes), toast with jam, eggs, and coffee. Photo Credit: Garrett Weisiger Daily German P.O.W. lunches consisted of pork roast, carrots, and potato salad. Photo Credit: Garrett Weisiger Daily German P.O.W. dinners consisted of meatloaf, bread, and milk. Photo Credit: Garrett Weisiger

Louisiana Camps

jacob levron staff videographer The Place Bar served as the dining hall for the POW Camp in North Thibodaux. Photo Credit: Jacob Levron, staff photographer The POW camp in Valentine, Louisiana, in 1943. Photo Credit: Nicholls Archive The Thibodaux camp’s POW soccer team. Photo Credit: Nicholls Archives Tents at the North Thibodaux POW camp. Photo Credit: Nicholls State Archives, Litt Martin Collection Scrip, a form of currency valid only within the camp, paid to German POWs at the camp in Ruston, Louisiana. The Shreveport Journal March 16, 1979 other coverage Camp Ruston by Louisiana Public Broadcasting https://youtu.be/EjcbeKd4Y2s?si=zd_1HD2O4bP70Slu Most Endangered Places: Camp Ruston by Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation https://youtu.be/vyS2VH9LoUw?si=2-0xu0Bo1ul2QBdR Thousands of German POWs in Acadiana During WWII The German P.O.W Camp at Camp Polk, Louisiana

Bayou Region Camps

aynsley andras staff writer More than 12,000 prisoners of war (POW) were sent to Louisiana during World War II, with 2,073 sent to camps in the Bayou Region to live in the communities and work the local industries. “You take a soldier out of the war to ship him 5,000 miles away,” says Glenn Falgoust, local historian and Vacherie native. “He’s as scared of what’s going on to him as the people sitting in their homes around Donaldsonville are of him. So it’s a mutual scenario.” “You take a soldier out of the war to ship him 5,000 miles away — He’s as scared of what’s going on to him as the people sitting in their homes around Donaldsonville are of him.” Glenn Falgoust Between 1942-1945, more than 425,000 prisoners of war were sent to over 700 camps throughout the United States, mostly located in the South and Southwest, according to the National Park Service. In the Bayou Region, POWs were housed in areas to help with local industry like sugar cane. “They [local men] just left the territory for like four years, so these sugarcane plantations were in trouble,” says Falgoust. “With no labor, you can’t produce a crop. So here comes the big question about the POWs, what to do with them.” Several camps were located in the Bayou Region including Donaldsonville, Thibodaux, Houma and Montegut. The Thibodaux camp, located in north Thibodaux on Coulon Road, housed 485 prisoners. Donaldsonville hosted one of the biggest camps in South Louisiana at the Donaldsonville State Fair Grounds, housing about one thousand prisoners, says Falgoust. The Houma camps came later because of a War Department rule preventing camps within 150 miles of any coast, according to the book Hard Scrabble to Hallelujah Legacies of Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana by Christopher E. Cencac Sr. and Claire Domangue Holler. But Louiaiana’s senators got the rule changed so prisoners could work in the sugarcane fields. The first camp in Houma was located near North Woodlawn Plantation house on Woodlawn Ranch Road and the second was on West Main Street between Boykin Street and Wolfe Parkway near Terrebonne High School. The prisoners ranged from 16-50 years of age, and life in the camps was strict, Falgoust says. The prisoners were not allowed anything relating to the war once they were captured. They were, however, allowed to write letters to their families. The POWs would work six days a week at farms and would start their days at 4 a.m. Prisoners in the Thibodaux, Houma, and Donaldsonville camps worked mostly in the sugarcane fields. Depending on the location of the camps, the prisoners would work on planting trees, shrubs, cotton, rice, and sugar. The local farmers were responsible for transporting their prisoner workers. Falgoust says the policy was that prisoners who did not work did not get to eat. Some of the prisoners of war got close to the families at the sugarcane farms where they worked. Some would even feed the prisoners. “I do know they were very hungry,” says Linda Theriot, an executive at Houma Regional Military Museum. “They didn’t get a lot of food. The owners of the plantation and the neighbors would invite them in to eat. These prisoners of war were not per se criminals for the community. They were criminals only for war.” Blimp at the Houma Naval Air Station where the German POWs were employed during WWII. Photo Credit: Regional Military Museum Hospital and kitchen at the Thibodaux POW campsite. Photo Credit: Evert Halbach Collection and Nicholls Archives & Special Collections Blimp base at the Houma Naval Air Station where the German POWs were employed during WWII. Photo Credit: Regional Military Museum German POWs walking at the Thibodaux campsite. Photo Credit: Evert Halbach Collection and Nicholls Archives & Special Collections Blimp base barracks at the Houma Naval Air Station where German POWs were employed to plant trees during WWII. Photo Credit: Regional Military Museum Thibodaux German POW campsite. Photo Credit: Evert Halbach Collection and Nicholls Archives & Special Collections Deflated blimp at the Houma Naval Air Station where the German POWs were employed during WWII. Photo Credit: Regional Military Museum Prisoner tents at the Thibodaux campsite. Photo Credit: Evert Halbach Collection and Nicholls Archives & Special Collections Sketch drawn by a German POW of the PeeWee Falcon House in Donaldsonville. Photo Credit: Glenn Falgoust

POW Camps in the Bayou Region

kade bergeron features editor When most think of World War II, the focus shifts straight to military involvement, Adolf Hitler, the Holocaust, and a war thousands of miles away. But the impact of the war came to the Bayou Region of South Louisiana as prisoners of war were brought into camps to help with local industry while workers fought overseas. “My mother and her cousins used to ride their bikes alongside the camp in Mathews when they were little,” says Wendy Phillips, resident of Raceland. “The prisoners were there, mostly to help pick up sugarcane scraps from the sugarcane company.” “My mother and her cousins used to ride their bikes alongside the camp in Mathews when they were little.” Wendy Phillips Throughout the region, prisoner-of-war (POW) camps were set up to contain the Axis soldiers and assist in labor shortages. In all, Louisiana was home to 52 POW camps throughout the state, according to the National World War II Museum. In the United States as a whole, more than 425,000 prisoners of war were sent to over 700 camps with most located in the South and Southwest, according to the National Park Service. There were multiple reasons for prisoners to be captured and dispersed at the camps. The start of this operation came from Great Britain, which had an abundance of prisoners who were filling up their camp’s space, therefore the United States agreed to take some in, according to the Prisoner of War Labor article in the Nicholls State University archives. Specifically, Louisiana had thousands of men deployed in the war, leaving farms, crops, and agricultural businesses without abundant labor. There were severe shortages of workers for these industries, and this allowed prisoners to be put to work to support and boost the American economy during the war. Prisoners mostly worked in the sugar, rice, and cotton industries, according to the Bayou Stalags article in the Nicholls State University archives. The Bayou Region parishes were home to over six camps including areas such as Thibodaux, Houma, Lockport, Mathews, and Donaldsonville, with a combined total of 2,555 prisoners as of 1945 data associated with the Nicholls State University Archives. The sole industry for the camps of the Bayou Region was sugar. For many current residents of the area, the prisoner-of-war camps along the bayous are completely unknown. Danielle Boudreaux, a resident of North Thibodaux, lives directly across the street from the POW camp location on Coulon Road in Thibodaux. Her home’s location is part of the historical site that housed 482 prisoners on its campus assisting directly in sugar cane production. “The neighborhood’s original two members just recently passed, and most likely the majority of the information regarding the camps went with them as well.” Danielle Boudreaux, who lives nextto the former Thibodaux POW camp location. “For me personally, I know very little about the camps, but I can guarantee there are some in this neighborhood that know nothing about it,” says Danielle Boudreaux, who lives on North 7th Street next door to the Thibodaux POW camp location. “The neighborhood’s original two members just recently passed, and most likely the majority of the information regarding the camps went with them as well.” Currently, the remnants of camps across the region have very little evidence of their past. It is hardly recognizable. The Thibodaux camp is now a residential neighborhood and a John Deere facility. The Lockport camp is a chemical plant, and likewise, the same can be said regarding the other Bayou Region locations. There are traces of families of German descent from World War II here in Southern Louisiana, as well as elderly community members who remember these camps from when they were children. To keep these local stories alive, Garde Voir Ci will unpack the life of the prisoners, the area of the camps, and their impact on the region. POW Camps in the United States during World War II The POW camp in Valentine, Louisiana, in 1943. Photo Credit: Nicholls Archive The Thibodaux camp’s POW soccer team. Photo Credit: Nicholls Archives Tents at the North Thibodaux POW camp. Photo Credit: Nicholls State Archives, Litt Martin Collection Scrip, a form of currency valid only within the camp, paid to German POWs at the camp in Ruston, Louisiana. The Shreveport Journal March 16, 1979 Thibodaux German POW campsite. Photo Credit: Evert Halbach Collection and Nicholls Archives & Special Collections Hospital and kitchen at the Thibodaux POW campsite. Photo Credit: Evert Halbach Collection and Nicholls Archives & Special Collections Portrait of Military employees John Hoffman, Mike Harris, Mary Snelling, and Charles Torrey in front of Camp Headquarters. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Captured German submarine U-505 with escorts. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Aerial view of road outside Ruston Camp. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Camp Ruston’s Christmas Dinner Menu. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection. Grave site of German Soldier Ernst Paul. Photo Credit: LDL/Louisiana Tech University/Camp Ruston Collection.