Night Out // Bayou Night Life

by Brandy Dunbar, staff videographer

Cultural Blending // Vietnamese Culture

by Madison Boudoin, Staff Writer Many refugees of the Vietnam War found themselves in the Bayou Region of Southern Louisiana, surrounded by rich Cajun culture and opportunities for work. The journey across the world was tough and risky, but it is greatly appreciated by the young Vietnamese generation living on the bayou today. “It makes me feel grateful that I have the opportunity for a proper education and to pursue a career of my choice instead of having limited options,” says Tri Tran of Houma, whose family traveled from Vietnam to America. Refugees were limited to specific careers in America due to a language barrier and a lack of education. There were only a few options to choose from. Unlike his father, Tri has the resources to choose any career path that he wants. Tri’s father left Vietnam after the war, when the North began taking over the South. According to Tri, his father’s dream— a dream that was shared among fellow Vietnamese refugees— was to create a better life for himself and for his future family in the land of the free. Thanks to his father’s escape from Vietnam, Tri is now pursuing a degree in business administration at Nicholls State University. Tri says that the refugees came to America on over-crowded ships. Many did not survive the voyage. Disease and illness spread quickly aboard the ships because of the cramped living conditions. Other refugees were caught in dangerous storms and pirate attacks that left them dead according to the CBS Digital Archives. Brandy Vo, of Houma, says that her parents sacrificed a lot to come to America. “It makes me sad to think about the sacrifices that my family made to get here. They traveled across the world to a new location to make sure their future generations— my generation— would have a better life,” says Vo. The Vietnamese searched for jobs upon their arrival in America. Groups of refugees fled to the Bayou Region for job opportunities, as they had very little money and clothing. Refugees generally only spoke Vietnamese, so it was important to find work that did not require the English language. Many discovered careers in fishing, shrimping, and crabbing in the bayou’s seafood industry. This was also the best career choice for refugees who wanted to make a decent amount of money without needing an American education. “The reason why a lot of refugees chose this type of profession is because they didn’t really need to talk to get the job done. A lot of body language was used instead. They simply watched the Americans do the work, and learned the profession from them in that way,” says Vo. Vo learned Vietnamese from her parents as her first language. She didn’t learn English until she started Kindergarten. This made it difficult for her to fit in with the other children. “I got teased a lot. Thankfully they had a program at my school called ESL— English Second Language— and this was how I learned to speak English,” says Vo. Vo’s parents know very little English to this day. Her father is part of a fishing crew, and her mother works in a seafood packaging factory. Neither job requires fluency in English. According to Vo, Vietnamese families contribute to the seafood industry of the Bayou Region, which is an industry that will never go out of style in Southern Louisiana— an area known for so many authentic Cajun seafood dishes. Not only are the Vietnamese helping to keep the traditional Cajun culture alive through careers in the seafood industry, but they are also striving to preserve their own culture and traditions of Vietnam. Vo says that Vietnamese communities are smaller on the bayou than in other areas of Louisiana, and they tend to stick to the traditional ways of the Vietnamese culture. This includes practicing Buddhism. Chua Chan Nguyen is a Buddhist temple located in Houma, Louisiana. The temple serves as a place of worship for the Vietnamese communities in the area. People also gather at the temple to celebrate the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, the most important traditional celebration of the Vietnamese culture according to Vo. “The Vietnamese community on the bayou remains very old-fashioned. A lot of Vietnamese still cook the same traditional food that was cooked in Vietnam,” says Vy Truong, a student at Nicholls State University. Truong says that a few Vietnamese people on the bayou are slowly starting to break away from the traditional ways, but most are staying true to their culture.

Bayou Sleeps // Unique Places to Stay

By Cullen Diebold, staff videographer

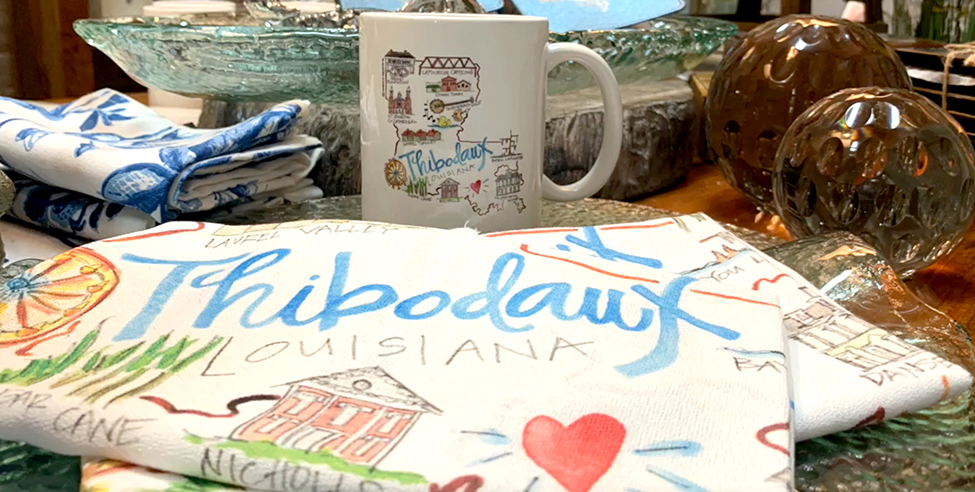

Bayou Souvenirs // Unique Gifts

by Brandy Dunbar, staff videographer

Bayou Lore // Hauntings

by Ashlyn Verda, staff writer Louisiana’s Bayou Region is rich in haunted history. Over generations, locals have passed down dark tales from the bayou, including legendary haunted swamps and plantation ghost stories. As time passes, and stories become more and more embedded in Cajun culture, the line between fact and folklore begins to blur. One of the most famous hauntings of the Bayou Region is known by students and faculty at Nicholls State University in Thibodaux. Ellender Hall, one of the student residence halls on campus, is known for its strange occurrences. According to Megan Henshaw, the assistant hall director, residents claim the dormitory is haunted by Helen Ellender helerself. A portrait hangs in the entrance of the lobby and students say her eyes follow you. Henshaw is also the resident assistant on the sixth floor. She says students have reported lights turning on and off, objects moving on their own, footsteps, and scratching noises. “Some say it’s the ghost of a student who died there in the 1970s,” says Henshaw. “It’s rumored that she fell to her death by jumping out of her sixth-floor window.” Although many students treat this story as fact, The Nicholls Worth reported that there is no record of anyone’s death or suicide in Ellender Hall. Not far from Nicholls is the Laurel Valley Plantation and Historic Village. The village contains cabins that can be seen from the road, and is said to be haunted by apparitions dressed in old-fashioned clothing. Visitors have also captured unexplained “floating lights” in their photos, according to volunteer worker Johnny Thibodaux. Locals are the first to experience these unexplained events. Sometimes, just by taking a shortcut on the way home. Devil’s Swamp, in Schriever, is appropriately named. An old train track runs across the road, allegedly haunted by the ghosts of buried slaves from Acadia Plantation, as well as the ghosts of people murdered or killed on the railroad tracks. When cars park or stop over the tracks, they reportedly begin to violently shake. There have also been claims of stalled cars, windows fogging, and handprints appearing on the windows. Ducros Plantation is also located in Schriever. The property is now privately owned by Richard Bourgeois and Angela Cheramine, who have restored the home. Dating back to 1802, no unusual deaths have been reported, but locals have passed on its ghoulish tale. “It’s not certain, but there is said to have been a young child who accidentally drowned in a nearby well and listeners can hear cries,” says Cheramine. Cheramie says the most common activity reported is inexplicable sounds. When they were restoring the house, carpenters claimed to hear footsteps from the main hall. Richard himself has heard a strange dragging noise on the upper gallery. Some supernatural experiences happen a little too close to home for locals. Coteau Road, located in Houma, is known by locals for having apparitions that wander the fields at night. More common sightings happen around metal sheds that can be seen from the road. The metal sheds and surrounding property belong to the grandfather of Houma resident Glynn Prestenbach. The road is very curvy in some areas and Prestenbach says many people have been injured or killed. Over the years, he has helped repair fences up and down Coteau Road, but has never seen anything unusual. “We have lived on Coteau road all my life and I will be the first to say it is haunted,” says Amber Bourgeois. “I have witnessed a man, a little boy, and a lady walking across the street. It doesn’t scare me though, they don’t seem to mess with anyone.” Located near the bottom of Houma and isolated from civilization, a historic ridge lies southwest of Bayou Dularge near Lake Decade. Mauvais Bois Ridge, is the source of nightmares that have been passed down by generations of United Houma Nation families. Mauvais Bois, named after a French term for “bad woods,” has been haunted since Vincent Gombi, Jean Lafitte’s battle companion, discovered the ridge. According to Nicholls State University Louisiana History Professor, Steve Michot, Gombi was trying to find a route near the Mississippi River during the Battle of New Orleans. “American Indians living on the ridge helped Gombi sink a British ship called the Josephine,” says Michot. “They cut down cypress trees from the woods so a barricade could be formed and the British could not cross Bayou Penchant.” To this day, it is said that the dead rise from the sunken Josephine and continue to linger over the land. Further down the bayou lies Bayou Sale Road, a long, curvy, and deserted road connecting Dulac to Cocodrie. Also known as LA-57, it is rumored to be one of the most haunted places in Southern Louisiana. Locals are familiar with the stories of a man on the side of the road looking for a ride. According to the locals, when cars slows down to pick him up, he either disappears or the driver notices that he is somehow transparent. The legend also claims that if a driver stops to pick up the ghost, they will receive treasures and good luck in return. “Ever since I was little, I’ve heard strange stories about Bayou Sale Road. I’ve traveled down the road many times and personally, I haven’t seen any ghost,” says Houma native Kate Planchet. “But it is a dangerous place and I get a bad feeling when I have to drive it by myself.” Local legends about hauntings are often passed down from generation to generation and have become a part of the Bayou Region culture. Although it has become difficult to determine folklore from fact, there is no denying that locals are interested in the unexplained. Many of these locations can be accessed for free and seen from the road, but simply stopping by and talking to the locals is where the real adventure begins. A dangerous curve in Bayou Sale Road that is surrounded by marshlands. Trees lining the curve of Coteau Road.

Scenic Drives // Louisiana Trails and Byways

by Brandy Dunbar, staff videographer

Bayou Welcome // Cajun Coast Center

by Wes Barnett, staff videographer

Making Music // Recording Studio

by Ashlyn Verda, staff writer Hidden in the quaint suburbs of Houma, Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions serves as an essential recording studio for musicians in the Bayou Region. Pershing Wells— a professional guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter from Bayou Black— owns Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions, where he works with local songwriters to develop their music into tunes that are ready for the radio. “I’m the guy they come to locally,” says Wells. “I’ve produced about 75 albums and more than 1200 songs.” Since the studio’s opening in 2002, Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions has helped professional musicians with producing and recording their songs. The studio also offers guidance with the mastering and arranging of songs. “When you arrange a song, you’re basically taking all the musical elements and reordering them and changing the sounds you hear in order to create a unique experience,” says John St. Marie, a musician, conductor, and educator at Nicholls State University. Wells says he enjoys the process of figuring out where he can take a song. However, he’s cautious about repeating arrangements for different clients. One of his main goals is to discover the different ways he can capture the uniqueness and originality of a song. To find that originality, Wells likes to hear clients perform their song with just an acoustic guitar and their voice. While listening, he’ll usually find a tempo that matches the song. “I think I have a very good talent for hearing what they are trying to do—the feel of the song,” says Wells. After hearing the barebones version of a song, Wells begins arranging and composing the rest of the instrumentals. Although he creates most of the instrumentals digitally, Wells sometimes brings professional musicians and session players. These musicians are usually keyboardists, guitarists, violinists, fiddle players, and steel guitar players from the Bayou Region. “My favorite thing is watching a client listen to their song after it comes to life for the first time,” says Wells. “I’ve seen some tears and I’ve seen some beautiful smiles. Nothing beats it.” Most of Wells’ clients are local. Veteran singer, songwriter, and bassist Tim Dusenbery worked with Wells on his 2004 record Kingdom Come. “It’s been a desire of mine to express myself through music,” says Dusenbery. “I heard great things and decided to team with Pershing to complete the album. The recording process went smoothly and I don’t know how I would have done it without him.” Wells began playing music at 14-years-old, when his eldest brother Bill brought home a Sears Magnatone guitar. He started playing by ear and developed the skill quickly. After jumping between a couple local bands, Wells moved to Colorado and became a full-time musician. “Like everybody else, I was hopeful that some break would happen. I took it as a five year musical sabbatical, during which I continued to hone my musicianship,” says Wells. Wells eventually moved back to Louisiana to start a family. Locals knew him at the time as a guitar player, rather than a producer. After taking a year off from playing music, he joined the Country Sunshine Band. From the 80s to the mid 90s, Wells featured as a session guitarist in dozens of local “Swamp Pop” singles and albums. He also performed multiple times at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. While working as the chief engineer at Houma’s Apple Tracks Recording Studio, Wells released his first CDs as a producer. At Apple Tracks, Wells taught himself how to professionally record and produce music. After being laid off from Apple Tracks, Wells began recording with his brother, which evolved into recording a full album. From that point forward, Wells received a steady flow of calls from clients asking for help on their albums and songs. The influx of requests made Wells realize that he didn’t have time for a day job. By 2005, he had a waiting list of clients and was able to place his recording studio next to his home. By helping local artist with their careers, Wells has contributed to keeping cajun, zydeco, and swamp-pop music styles alive in the Bayou Region. Some local favorites Wells has worked with include Don Rich, Joe Barry, Southern Cross, and Tab Benoit. The music by these musicians and other local legends can be found at Fabregas Music Store in Houma. These days, Wells, in addition to recording and producing for local artists, still finds time to tour and play live with his friends. Visitors to the Bayou Region can catch him at seasonal festivals, The Balcony Bar, and On The Canal Bar, where he regularly plays. Even though Wells has become successful enough to move away from Houma, he’s decided to stay. “A lot of people ask me how come I don’t go to Nashville,” Wells says. “I’m content here. I feel that I’m a resource that is needed in this area.” For more information regarding Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions, contact Pershing Wells at http://www.pershingwells.com/digital_sac_a_lait_productions.htm.

Cajun Eats // Seasonal Eating

by Sam Gruenig, video editor

Kid Scene // Bayou Country Children’s Museum

by Sydney Moxley, staff videographer