A Gas Leak // The Evacuation of Grand Bayou

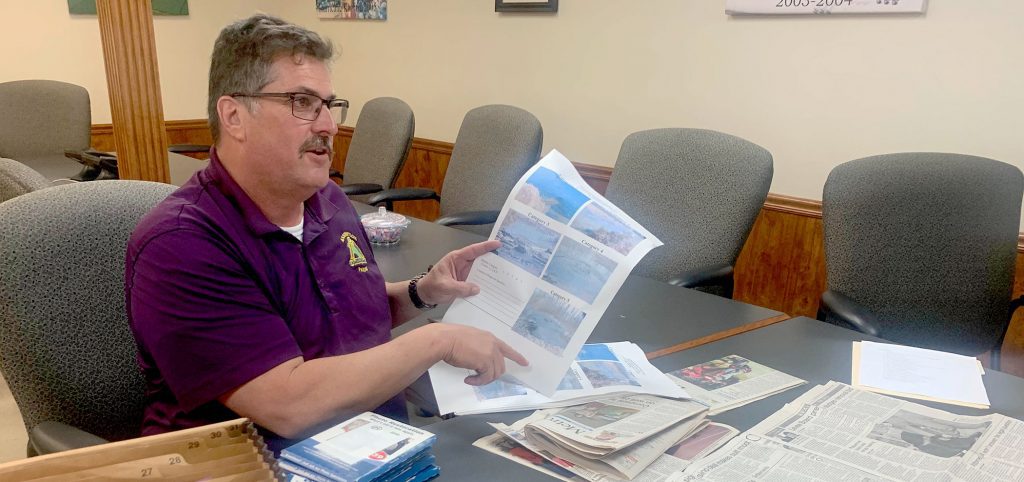

By Emilee Theriot, Staff Writer Christmas is a time to spend with loved ones, a time of giving and a time to make new memories, but for John Boudreaux and the Grand Bayou community, Christmas of 2003 was anything but festive. As the director of the Office of Emergency Preparedness for Assumption Parish, Boudreaux was the person who received emergency calls for the parish. So to get a call about a brine leak from Dow Chemical, which had been operating in the area since 1956, was normal. Except it was Christmas Eve. And when he got to the Grand Bayou Dow Chemical facility, water was jetting 20 feet into the air. “It sounded like a jet engine. It was an ‘oh shit’ moment,” Boudreaux says. Company representatives first thought it was a brine leak and later deemed it a natural gas leak, Boudreaux says. Natural gas has no smell, so it is difficult for the average person to know if they are in danger and it’s hard to know what’s causing the leak. But Dow Chemical did note that Gulf South had natural gas pipelines in the area. Boudreaux says he met with Vernon Self, a Gulf South representative, at the site and asked about the cause and the extent of the gas leak. Without an explanation from Self, Boudreaux eventually left the site and instructed Gulf South to call if it got worse. On Christmas morning, Self called, and Boudreaux returned to the site. Boudreaux’s phone rang again, this time it was Nolan Blanchard, a Grand Bayou resident, calling to say the ground in and around his yard was bubbling. Boudreaux immediately rushed to Blanchard’s home with his air monitoring equipment, and he picked up a slight hint of a lower explosive limit on the monitor. “This ain’t good,” Boudreaux says he thought to himself. Boudreaux then called Marty Triche, the president of the Assumption Parish police jury, to inform him that residents needed to evacuate. Boudreaux said he knew it would not be a popular decision, but the safety of the public was his number one concern. “It was the toughest decision I ever had to make,” Boudreaux says. Residents were told late Christmas afternoon they had four hours to evacuate. Residents were also notified that Louisiana Highway 70 would be closed at 10 p.m. Arrangements were made to house the residents at a local hotel near the Sunshine Bridge. Twenty-eight residents evacuated to the local hotel. Tracy Scioneaux, 30 at the time of the gas leak, says she was celebrating Christmas with her family at her mother’s house when a volunteer firefighter friend told them they were planning to evacuate the residents of Grand Bayou. “My mom always told us something’s going to happen here.” Scioneaux says. “We had to pack up all our food and bring our presents we had just opened and some that we didn’t.” The evacuation lasted 52 days. Scioneaux says the days were hectic at first. Gulf South plugged rigs into the salt cavern and dug them into the water aquifer to allow gas to escape and reduce the pressure. Gulf South found a crack in a casing that went down to the salt cavern, causing too much pressure. Boudreaux says he kept the public informed the best he could. At one point there were five state agencies on site: Department of National Resources, Department of Environmental Quality, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Louisiana State Police and the governor’s office. On the local level, there were representatives of the sheriff’s office, OEP and the fire department. Gulf South, Dow Chemical and the various rig companies were also on site. Boudreaux and company officials briefed the evacuees every evening at the hotel. Scioneaux says Gulf South officials did their best to answer their concerns. Boudreaux adds that while friction between company officials and public officials rose, they all continued to work together to resolve the situation and accommodate the public. A public meeting was scheduled for Jan. 13, 2004, at the No Problem Raceway lounge. The crowd was so large, makeshift bleachers were erected outside to accommodate the several hundred people that showed up. Public officials also followed up with fliers updating the progress throughout the ordeal. “They did a really good job on taking care of the people,” Scioneaux says. “They took responsibility.” Gulf South paid for the evacuees’ food and lodging at the hotel. After a period of time it was agreed by Gulf South and the evacuees that Gulf South would start paying an allowance rather than pay the hotel bill, giving evacuees an option of where to stay. Scioneaux’s family rented a house in Napoleonville with her brother’s family. Gulf South also paid for people to clean the evacuees’ homes prior to moving back. After moving back to their homes, Scioneaux and her husband, along with all the other Grand Bayou residents, were approached by Gulf South to purchase their home and land. “The older people didn’t want to leave, but eventually, everyone sold their houses and moved from Grand Bayou,” Scioneaux says. “It was a change of life.” “We don’t blame the companies because without companies we wouldn’t have a livelihood,” she continues. “But, it was disheartening knowing that on Christmas Day that happened in 2003 and my mom died in 2005, so toward the end of her life this is what we had to go through.” Natural Gas Vent Vent well installed in Grand Bayou to vent the gas from under the property. The Assumption Pioneer, February 19, 2004 The Assumption Pioneer, February 19, 2004

Natural Resources // Grand Bayou’s Salt Domes

By Emilee Theriot, Staff Writer In addition to a bounty of fish, animals and plant life above ground, the earth beneath Grand Bayou is rich with natural resources like salt domes, natural gas and oil. “Wherever you have a salt dome, somewhere along the line there is oil and gas,” Jerry Rousseau, a Grand Bayou resident, says. The first salt dome in Assumption Parish, which became known as the Napoleonville Salt Dome, was discovered in September of 1926, according to a 1927 article in The Assumption Pioneer. The largest of the 68 salt domes discovered in Louisiana, the Napoleonville Salt Dome was about one mile by three miles. It began at 700 feet below the surface and went to a depth of 30,000 feet. Dow Chemical began purchasing the land above and around the salt dome in 1956, according to the conveyance records at the Assumption Parish Clerk of Court office. The company purchased 103 acres from Schwing Lumber, a large landowner in the area, and 169 acres from the Leblanc family as well as several hundred acres from dozens of families. Each act of sale included language that the sellers reserved a five-cent-per-ton royalty from the sale of the salt removed from the dome. Dow wanted the salt domes to use the brine in making plastics in their chemical plants along the Mississippi River, Rousseau says. To mine the salt, the company drilled a well in Grand Bayou and pumped hot, fresh water into the salt dome, which eroded the salt from the dome, says John Boudreaux, the director of the Office of Emergency Preparedness for Assumption Parish. The mixture of the fresh and saltwater created a solution called brine. A second well was drilled from above ground and entered the new salt cavern to retrieve the brine. The brine was pumped out of the salt cavern into above-ground storage tanks. Once above ground, the brine was shipped by truck to the Dow Chemical plant in the nearby city of Plaquemine in Iberville Parish. The plastics produced using the brine were shipped from the plant along the Mississippi River to various other plants throughout the United States. The plants would then use the various plastics to make consumer products like toys, paint and appliances. This system worked for many years. But as salt was removed from the dome,it left an empty cavern within the salt dome, Boudreaux says. And a typical cavern is the size of 50 Mercedes Benz Superdomes — underneath homes and communities. Then in the 1960s and 1970s, various oil companies leased the caverns from Dow Chemical to store oil and gas. With the dome so big, Dow allowed Texas Brine to begin extracting brine from the Napoleonville Salt Dome in the 1960s. Rousseau’s father was the first employee at the Texas Brine Grand Bayou facility. “My dad’s job was to make sure the plant was run correctly,” Rousseau says. “Trucks would come in and pump the brine into the tanks and bring them where they needed to go.” Now, most of the brine is transported via pipeline. Brine continues to be removed from the salt dome and delivered to chemical plants along the Mississippi River in Taft, Geismer, Gramercy and Plaquemine. The more brine removed allows for more oil and gas to be stored. Today, there are over 60 caverns located in the Napoleonville Salt Dome. Boudreaux says a few more permits are pending to develop more caverns in the Napoleonville Salt Dome.

David Rousseau

Current Hometown: Plattenville Favorite Thing to Do Hunt and fish. Favorite Memory The close knit communities and family lifestyle. Most Missed I miss being so close to the outdoors. Grand Bayou Traditions I’m still best friends with my childhood friend, and we still have breakfast on the weekends near Grand Bayou. I’m still best friends with my childhood friend, and we still have breakfast on the weekends near Grand Bayou.

Jason Blanchard

Current Hometown: Houma Favorite Thing to Do Anything having to do with outside; shooting my pellet gun, crawfishing, playing in the woods. Favorite Memory Watching my grandfather work under an oak tree, washing cars, fixing a lawn mower, building a BBQ pit. All this was done on a Saturday morning. Most Missed I miss the people and families and how close everybody was. Grand Bayou Traditions My treatment of others and compassion and ability to see people for who they really are is something that I learned in Grand Bayou and that shaped me the most. [My favorite thing to do was] anything having to do with outside; shooting my pellet gun, crawfishing, playing in the woods.

Jerry Rousseau

Current Hometown: Paincourtville Rousseau was born in Grand Bayou and lived there for 19 years. Favorite Thing to Do Fish, hunt and swim. Favorite Memory It was a quiet, family-oriented place where you didn’t even have to lock your doors. No one would ever bother you or ever try to steal from you. Most Missed Seeing all the people that lived there and all of the small family owned businesses including his grandfather’s store, moss ginn, dance hall and casino. Grand Bayou Traditions It was the place I grew up in and always loved. It made me a friendly and more family-oriented person. It was a quiet, family-oriented place where you didn’t even have to lock your doors. No one would ever bother you or ever try to steal from you.

Joy Rousseau Banta

Current Hometown: Paincourtville Favorite Thing to Do Ride in a boat and fish. Favorite Memory My house was the go-to house, and my family had a shed that my friends and I would play in all day; as well as riding in a boat and fishing by rowboat. Most Missed I miss the community and the people. In my mind, I cand go down in the street and tell you where everyone stays. Grand Bayou Traditions We still get together as a family on Sundays I miss the community and the people. In my mind, I cand go down in the street and tell you where everyone stays.

Randy “Wop” Rousseau

Current Hometown: Belle River Rousseau was born in Grand Bayou. He moved away at 19, but moved back in 1991 and lived there until he was permanently evacuated in 2011. Favorite Thing to Do Being in the bayous before the alligators — there’s a lot of alligators in the water now that they didn’t have back then. Favorite Memory Probably playing football in the yard with the two other guys that lived there that were my age. That’s about it. There was just three of us and we played football in the yard and rode dirt bikes and stuff like that. We could ride dirt bikes in the yard, go crawling across the little bayou and go into the woods It was pretty cool. Most Missed You had room. You didn’t have any borders, you didn’t have any limits, you could go out and ride bikes and whatever. You could go through a neighbor’s yard. We had acres of land. We just had a lot of room. Grand Bayou Traditions There weren’t any rules or restrictions. You pretty much knew when you had to be home, you knew what you had to do, you knew when you did wrong. It was pretty good. We had good friends, had good neighbors, family all around, and we didn’t get in a lot of trouble because there was not really nothing to get into any trouble about. Evacuation Experience We had been evacuated in 2003 — actually Christmas Day of 2003 — for two months. We were told to leave, not knowing when we’d go back, if we’d go back- and one thing that bothers me particularly about that episode was that it was Christmas day and I had a lot of family at my house because I had a big house and everybody came over there. we had brunch, and the whole day’s events. In 2011 we were out permanently, but that was another incident with Texas Brine- so two completely separate incidents. You had room. You didn’t have any borders; you didn’t have any limits.

Education // Bayou Way of Learning

By Shaun Breaux, Features Editor Grand Bayou may not have been the biggest or most developed area, but for the people born and raised in this bayouside community, they made it work not only out of necessity, but because they enjoyed their way of life. “Being five miles away from everything, like the grocery store, church and school, we were kind of isolated in our own little beautiful community,” says Jessica Rousseau Baye, Grand Bayou native. “We had a wonderful childhood; we didn’t know that there was anything different to us.” Nell Aucoin Naquin, Grand Bayou native, says that although there may not have been many industrial places in the community, to them, there was a lot around. “I mean there was the great outdoors. The world was ours,” Naquin says. “We got to swim in the bayou everyday, we got to walk in the woods and look at all the animals and the creatures. We got to fish and supply our food from the animals, the land and the bayou. We grew our own food, so there was a lot to do and see.” Grand Bayou’s lone schoolhouse was abandoned in the 1930s. Once roads improved, children were able to travel or be picked up by bus to attend school five miles down the road in the nearby town of Paincourtville. Naquin says that old schoolhouse was where she was born and raised until she was about four years old. “My mom and my dad turned that house into our home. Eventually my momma bought that property and the building, tore the schoolhouse down and used the lumber from the schoolhouse to rebuild the house that I pretty much grew up in,” Naquin says. The children of Grand Bayou during Naquin’s childhood in the late 1950s attended St. Elizabeth’s School in Paincourtville about five miles away. They went to Catholic school until 7th grade and were taught by nuns. Baye says the Catholic foundation was essential for their education. Tuition for Baye and her siblings was $3 per person per month around this same time. Baye says for the four of them, that $12 was hard to come by. She says she remembered her parents struggling during some months, as Baye’s father worked as a small farmer on leased land. “Still, We always had a car, and we always ate well. I never felt poor, but when I became an adult, I knew we had been poor,” Baye says. From there, they attended 8th grade six miles away in Belle Rose and Assumption High in Napoleonville for high school 11 miles away. After high school, Naquin rode the public bus from Grand Bayou to Nicholls State University every day until graduation. Nicholls is located in Thibodaux, around 30 miles from Grand Bayou. Naquin says she knew a lot of Grand Bayou residents, herself included, who would not have been able to get a college degree if the parish would not have sent school busses to pick them up and bring them to Nicholls. She says she rode the school bus for her entire educational career and was thankful for the bus that picked them up every day. The generation before them had more than just a bus ride to endure. Baye says her mother went to school in Belle Rose, but it only went up to 11th grade. After graduation, her mother started teaching in Pierre Part, which she had to get to by boat. “My mother taught second grade with an 11th grade education. She was a very smart lady,” Baye says. Baye’s father only had a fifth grade education, but he continued to teach himself. “During the war, he was always reading Time Magazine and Newsweek Magazine, so he was self-educated. I think that when you’re in the war and you travel to other parts of the world that’s education in itself,” Baye says. The former residents of Grand Bayou talked about their childhood much like other rural communities of the 1950s. Yet unlike those communities, they had the bayou to explore, gaining an entirely different type of education and set of skills. Grand Bayou’s one-room schoolhouse before it closed in the 1930s. Grand Bayou’s one-room school class picture. St. Elizabeth School in Paincourtville about five miles from Grand Bayou. Previous Next

The Families // Settling Along Grand Bayou

Grand Bayou was just a few families with Acadian ancestry that collected together on the bayou. From the lineage of the largest of those families, the Rousseaus and Daigles, to the arrangement of their homes in the community, for those who lived in Grand Bayou, these details shaped everyday life.

The Settlement // How Grand Bayou First Came to Be

By Wes Rhodes, Staff Writer Gustave Joseph de La Barre, or “Gus,” as people called him, was born in 1864, and is considered the patriarch of Grand Bayou according to De La Barre: Life of a French Creole Family in Louisiana. The De la Barre family text says that Gus was a natural leader who could rally men into a business opportunity while joining them in partnership. Gus, the man who helped build Grand Bayou, adhered to the “living” principle. The principle stated that a “living” is not measured in money, but instead is measured in the way a man earns a livelihood, in harmony with family, life and needs. Gus spent his childhood traveling between Assumption Parish and New Orleans before his family settled in Assumption Parish at the age of 9. He did not receive much schooling, but this was not uncommon in the mid to late 1800s. As Gus grew into his teenage years, he taught himself how to read. In the 1880s, the lumber industry began to boom across the country, but especially in Louisiana. According to the Historic Context of the Louisiana Lumber Boom, in 1880 Louisiana was ranked 13th in the United States for the dollar value of its timber product. By 1900, the state was ranked 10th in the nation. The resurgence of the lumber industry prompted Gus, along with his brother Nelson, to start the Louisa Saw Mill in 1887. The De La Barre family text says that in 1891 the Louisa Saw Mill was bringing in enough income for the brothers to purchase a large piece of land to collect cypress tree lumber to haul back to the mill. By 1898, the Assumption Pioneer referred to Gus as, “Gus J. La Barre, the Grand Bayou sawmill king.” This was just the beginning for Gus’s claim to local fame, as he soon followed these accolades up by founding the settlement of Grand Bayou. Early residents of Grand Bayou consisted mostly of the sawmill workers and their families, but there was little in place for leisure. In 1905, Gus requested help from a business associate, Ulysse Hebert, to help create the first establishments in Grand Bayou, including the settlement’s first store. Jerry Rousseau, the grandson of Hebert, says his grandfather’s store was a one-stop shop that residents could go to and get almost anything they needed. “He sold anything and everything at his store,” Rousseau says. “He sold groceries. He sold clothes. He even sold literal iceboxes because back in those days they didn’t have refrigerators.” Hebert then built a dance hall, a casino and a moss gin. According to the De La Barre family text, by 1923 the small town added a bank, a school for children to attend grades one through four and a church, all which Gus de La Barre helped build and fund. Gus died in 1925, but left behind a community. Gustave de La Barre at his desk in Grand Bayou, c. 1910 The Labarre Brothers sawmill on Grand Bayou, c. 1900