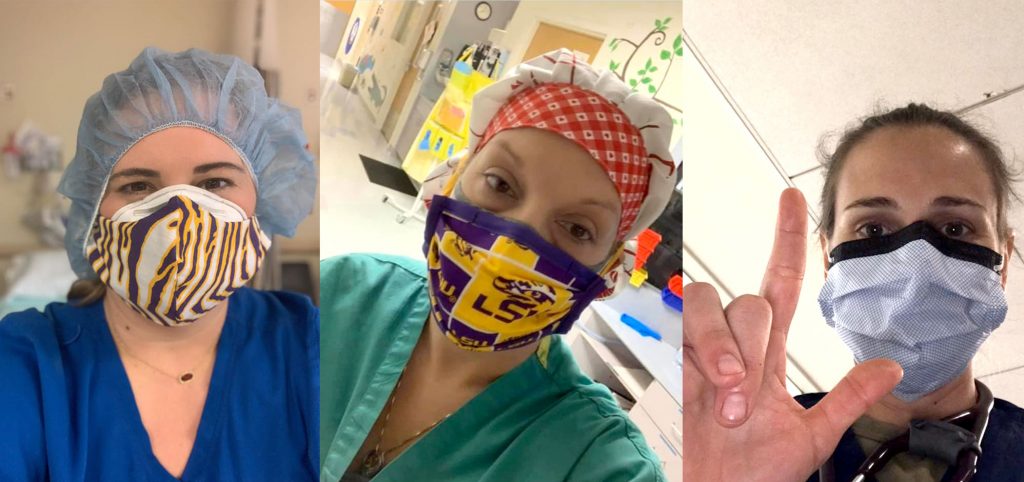

The Frontlines // COVID-19

Clelie Hebert Deployed to a field hospital in New York City with the US Army during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ashley Breland Nurse at Children’s Hospital New Orleans Aimee Breland Barrois Nurse at Ochsner Medical Center By Shaun Breaux, Features Editor Like most communities across the globe during the COVID-19 pandemic, the former community of Grand Bayou has come together to help fight the novel virus. From descendants fighting on the front lines as healthcare workers to those praying nightly together for them and the world, the tight-knit community that started in Grand Bayou has come together for this common cause. One of the ways they keep in touch is through social media, specifically a Rousseau Family Facebook group. Angela Diez, a Rousseau family member, posted on Facebook a list of the family healthcare professionals on the frontlines on the fight against the coronavirus. Children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of this Grand Bayou family make up a long list of warriors the family prays for. “O Holy Spirit, we thank you for the advancements that have led to improving the health of so many,” a prayer posted with the names reads. “We beg you to inspire new breakthroughs in overcoming the coronavirus and all serious flu viruses. Protect, we pray, health care professionals from the illnesses they are treating, and make them instruments of your healing. Amen.” Jessica Rousseau Baye, a Grand Bayou native, says one thing everyone carried with them when they left Grand Bayou was faith. “Everyone had strong faith,” Baye says. “I guess they just taught us how to be compassionate.” Another thing that remains consistent with the people of Grand Bayou is their nostalgia for the past. Some of their fondest memories are the simplest ones where they were just together. Betty Crochet Breland, Grand Bayou native, says her favorite tradition is the Rousseau family reunions where all the cousins would get together and tell stories. Now, however, in these unprecedented times, Breland says they are doing the best they can to stay connected. “Even though I may need a little help with all the technology side, I know my family is just a phone call away,” she says. Breland moved away from Grand Bayou at a young age but still says she always stayed connected with the people who taught her not just how to live, but how to enjoy life. Breland says, “Nothing changed then and it won’t change now.” on the frontlines Healthcare FRANCES “BELLE” ROUSSEAU CROCHET FAMILY Adam Ducoing, great-grandson Aimee Barrois, great-granddaughter Amber Sevin, wife of great-grandson Amelia Breland, wife of great-grandson Ashley Breland, great-granddaughter Brandon Treadaway, great-grandson Brooke Vincent, great-granddaughter Clelie Hebert, great-granddaughter David Katz, husband of great-granddaughter Dawn Hamblett, granddaughter Jennifer Ducoing, granddaughter John Dugas, grandson Kara Sims, great-granddaughter Kelly Arnold, great-granddaughter Kristin Russo, great-granddaughter Kurt Dugas, grandson Lauri Crochet, great-granddaughter Madeline Ducoing, great-granddaughter Mary Voisin, wife of grandson Tralles Rhodes, husband of granddaughter HAZEL ROUSSEAU AUCOIN FAMILY Alicia Grisaffe, granddaughter Candi Aucoin-Vendur, granddaughter Cynthia P. Grisaffe, wife of grandson Maci Alane Breaux, great-granddaughter Nell Naquin, daughter HAROLD “PICOU” ROUSSEAU FAMILY Allison Barbin, granddaughter Bert Blanchard, grandson ALMA ROUSSEAU LANDRY FAMILY Brandi Landry, granddaughter Cachet Mitchel, granddaughter Chad Landry, grandson Desiree Fairley, granddaughter Rebel Reavis, granddaughter ADDIE “DODD” ROUSSEAU FAMILY Kristi R Politz, great-granddaughter ICY “NICE” ROUSSEAU LEBLANC FAMILY Chelsie Dinino, great-granddaughter Holly Gaudet, granddaughter ELDA “SIS” ROUSSEAU GUILLOT FAMILY Tammy Henderson, granddaughter EARL ROUSSEAU FAMILY Jennifer Rousseau, wife of grandson Jessica Rousseau, wife of grandson OTHER FAMILY Terri Migliori, wife of great-nephew of Adele Dupre Rousseau and 2nd great-nephew of Marcellin Rousseau first responders ADDIE “DODD” ROUSSEAU FAMILY Tony Boudreaux, husband of granddaughter ALMA ROUSSEAU LANDRY FAMILY Dwayne LeBlanc, husband of granddaughter Jason Giroir, husband of granddaughter ELDA “SIS” ROUSSEAU GUILLOT FAMILY Tim Henderson, grandson Tyler Henderson, great-grandson

Moving On // Staying Connected

By Wil Rhodes, Staff Writer Though Grand Bayou was once a thriving community, over time, its residents moved away. The reasons, like better jobs, were many, with the last remaining families forced to relocate in the early 2000s due to salt dome mining. “There was just no work for the girls,” says David Schexnayder, whose grandparents and parents were residents of Grand Bayou. “My mom and one of her sisters left Grand Bayou and moved to Baton Rouge for work.” Most of Grand Bayou’s jobs were either in the salt mines or water activities, so many residents moved away for jobs in agriculture. Betty Breland’s parents were from Grand Bayou initially but moved to Bayou Corne. When Breland was six years old, her family had to relocate to Houma because her father got a farming job. “My dad was an overseer on a plantation, so that is why we left the area,” Breland says. Residents say they knew that their beloved community was beginning to die because of all the people leaving for jobs elsewhere around the state. “It was hard to make a living in Grand Bayou, there just were not many jobs in the community,” Breland says. Yet while people moved away, they would visit often. “My parents would always go back and visit, and mostly everybody stayed in the same spot,” says Schexnayder. Nell Naquin, a former Grand Bayou resident, now resides in New Orleans and says moving from Grand Bayou to New Orleans was not that difficult because she could still visit. But as former residents moved farther away and developed lives of their own, getting back to visit became harder. “Growing up, I would always go back and visit my cousins frequently,” says Breland, who moved away from Grand Bayou at an early age and eventually settling in Belle Chase. “It was just hard for me to get back and visit after I got married and moved to Belle Chase.” And now that it’s all gone, Breland says she misses things like crawfish boils. “Many people were scattered throughout the area at first, so it was just the little things like that I wish I was still able to do.” a grand (bayou) reunion 1956 ROUSSEAU FAMILY REUNION 2017 ROUSSEAU REUNION 1972 ROUSSEAU REUNION 1984 ROUSSEAU REUNION 1984 ROUSSEAU REUNION Tante Belle’s family 2018 ROUSSEAU FAMILY REUNION THE GRAND BAYOU GIRLS A 2016 picture of a group of ladies from Grand Bayou who got together periodically for lunch.

Always Together // St. Elizabeth Cemetery

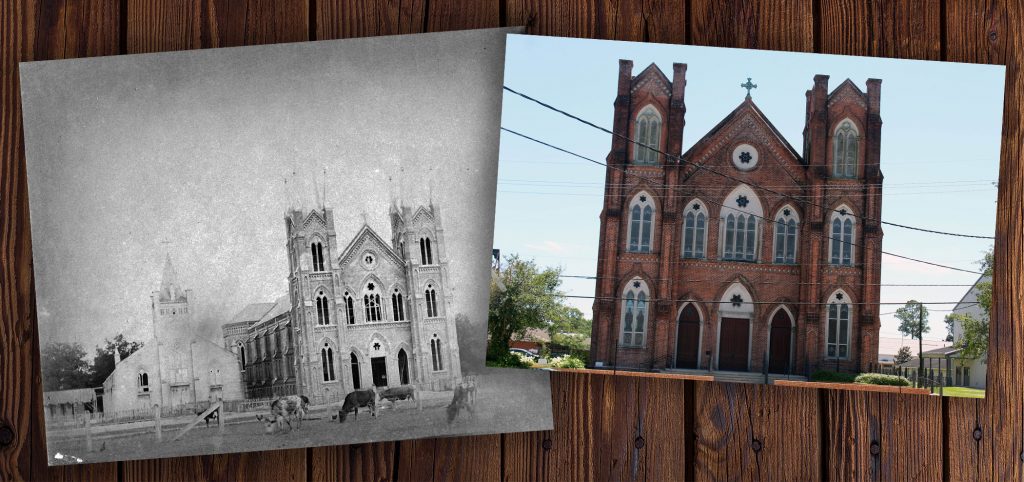

Grand Bayou // Then and Now

Adele “Mamere” Rousseau’s House Grand Bayou St. Elizabeth Church Paincourtville

Living On // Traditions

By Wes Rhodes, Staff Writer People who grew up living in Grand Bayou say it will always have a special place in their hearts. While the small community is no longer habitable for residents, the people of Grand Bayou left behind traditions that still keep the spirit of Grand Bayou alive today. An early Grand Bayou tradition was promoting the love and appreciation between family and friends. Grand Bayou was a small, close-knit community, and the vast majority of the people that lived there were related, says former Grand Bayou resident David Rousseau. Rousseau now lives in Plattenville, La., which is seven miles away from Grand Bayou. He says he recalls a time where everyone in Grand Bayou felt like family. “I remember being able to walk a short distance and being able to be at one my aunt’s or uncle’s houses or someone who was related to me in some type of way,” Rousseau says. “I feel like small, family-orientated communities aren’t very common anymore.” He says those strong family ties that were instilled in him as a child is something he still carries with him. “Family is important to me. I live on the same street as two of my sisters, so we are always getting our families together for things like crawfish boils and LSU football games.” Rousseau says this tradition of family gatherings reminds him of Grand Bayou, and he believes it is something that will get passed down to the next generation. Another tradition that remains with some people who lived in Grand Bayou is food. Nicki Boudreaux, whose family is from Grand Bayou, says the tradition of cooking her late grandmother Mabel Hebert Rousseau’s special dishes is something that not only keeps the memory of Grand Bayou alive, but the memory of her grandmother alive as well. “To me, my grandmother is Grand Bayou. We still talk about the things that MawMaw cooked,” Boudreaux says. So cooking the things she cooked or trying to cook the things she cooked is how Grand Bayou still lives on for me.” Boudreaux says she has her grandmother’s spaghetti and vegetable soup recipes down packed, but she stays away from trying to bake her grandmother’s famous pineapple upside-down cake. “Baking is not my thing, I never tried the upside-down pineapple cake because no one that has tried has been successful.” Boudreaux says like any real Cajun, the tradition that will always live on is food. Some traditions are started by families, while other traditions are created by circumstances. There was no sign of the internet in the 1960s when former Grand Bayou resident Clarence “Bud” Rousseau was growing up; however, he says back in those days he did not need it. Rousseau says there was enough to do outside to preoccupy his time almost every day. “I liked being outside as a kid growing up in Grand Bayou. My cousin and I would go catch crawfish or just go to the bayou and fish for hours at a time when school was out,” Bud says. Bud now lives in Thibodaux, La., and owns a camper and a boat. He says he still tries to get out as much as he can. “I’m much older now so I can’t take the boat out as much as I want, but when I do get the chance to put it in the water it always reminds me of fishing in Grand Bayou.” For Greg Leblanc, Grand Bayou native, the best tradition is picking turtle eggs. He says he used to go down to the bayou side to pick turtle eggs and still continues this fun activity with his grandkids. “Ever since they were two or three years old, I would still pick turtle eggs with them and hatch them,” LeBlanc says. “Had to show them how we did things in the olden days.”

Still Battling // Salt Dome Legal Case

By Emilee Theriot, Staff Writer On August 3, 2012, a sinkhole developed near the Napoleonville salt dome in Assumption Parish. After the sinkhole emerged, various parties filed lawsuits. Now, with the 8th anniversary of the Napoleonville salt dome sinkhole approaching, the legal battle is not done. “In all of my years working at the First Circuit, I have never experienced so many appeals from one incident,” says Rodd Naquin, the clerk of court for the First Circuit Court of Appeal. The lawsuits were filed by locals and businesses to recover out-of-pocket expenses, loss of profits and loss of business, among other damages. Local governmental entities, like the Assumption Parish Police Jury and the Assumption Parish Sheriff, sued to recover the cost to respond and monitor the sinkhole until the environmental disaster was brought under control. Various pipelines and drilling companies brought separate lawsuits against Texas Brine. In each of the lawsuits, the pipeline companies sought to recover damages to their respective inoperable pipelines due to the alleged negligence of Texas Brine’s operation of a brine production known as the OxyGeismer #3 well (OG3). Texas Brine responded to each lawsuit by asserting claims against various parties, seeking recovery for its own damages in the form of reimbursement expense for environmental response cost, litigation expense and lost profits. According to legal documents, Texas Brine began drilling and operating the OG3 well on property Occidental Chemical Corporation owned in 1982. Texas Brine was the sole operator of the well, which was solution-mined for almost thirty years. Texas Brine’s operation of the well provided brine to a plant owned by Legacy Vulcan Corporation (Vulcan). The OG3 well continued to expand the size of the cavern until it approached the Napoleonville Salt Dome’s western edge. A trial was held in Assumption Parish in the fall of 2017 to determine what caused the sinkhole to form and who, if anyone, was at fault. The evidence presented at trial established that the 2012 sinkhole was caused by three primary factors: the proximity of the OG3 cavern to the edge of the Napoleonville salt dome wall, a leak in the OG3 cavern, the plugging and abandoning of the OG3 well and cavern without continued monitoring of the loss of brine and reduction in pressure in the well and cavern. The trial court found the close proximity of the OG3 cavern to the edge of the Napoleonville salt dome was a substantial factor in causing the sinkhole. The close proximity allowed for the solution mining operations to create a thin cavern wall at the salt dome’s western edge At the time of Texas Brine’s drilling in 1982, Hook Chemical Corporation, now known as Occidental Chemical Corporation, owned the land. Vulcan was the mineral lessee of the salt dome, and Texas Brine was the operator of the well. According to the written reasons of the trial judge, the evidence showed that both Texas Brine and Vulcan knew, before the drilling of the well, that the salt dome’s edge was a serious issue that would require the parties to proceed with caution. With Vulcan and Texas Brine fully aware of the edge of dome concerns, Texas Brine continued to supply brine to Vulcan at an accelerated rate until Vulcan sold its interest in the salt dome to Oxychem in 2005. In its written reasons for judgment, the trial court pointed out in June 2008, Oxychem’s expert recommended that Oxychem terminate mining the OG3 cavern and expressed concerns of environmental risk, including the remote possibility of a sinkhole. Oxychem discussed the expert’s recommendations with Texas Brine and both parties possessed the authority to immediately terminate the OG3 operation. The trial court found both parties placed financial and business interests above environmental concerns. The OG3 well was plugged and abandoned in early June 2011. The trial court noted in its reasons for judgment that both Texas Brine and Oxychem failed to prudently monitor the OG3 well by not assuring that the OG3 well cavern reached pressure equilibrium before plugging and abandoning. The trial court found the evidence showed Texas Brine and Oxychem were equally responsible for the untimely plugging and abandoning of the OG3 cavern and its contribution to causing the Napoleonville salt dome sinkhole. “A common theme of this case is that Oxychem, Texas Brine, and Vulcan each placed their economic interests over environmental and safety concerns,” says Trial Judge Thomas Kliebert, Jr. The warning signs were present for each party; however, each party was affected by the financial implications of their actions. On December 21, 2017, the trial court signed a judgment allocating fault as follows: Oxychem was assigned 50 percent of fault, Texas Brine was assigned 35 percent of fault and Vulcan was assigned 15 percent of fault. The trial court assigned the most fault to Oxychem because the court found Oxychem possessed superior capacity over Texas Brine and Vulcan to prevent the Napoleonville salt dome sinkhole. Texas Brine was allocated a significant percentage of fault for negligently operating the OG3 well/cavern system and Vulcan was assigned the least percentage of fault for its actions in the early stages of the OG3 well. The judgment of the trial court did not end the sinkhole litigation. The parties have appealed the trial court’s ruling. Various appeals are pending at the Louisiana First Circuit Court of Appeal. According to Naquin, the sinkhole incident accounted for 80 appeals and 255 writs. “To put that into perspective, one must understand the First Circuit Court of Appeal hears appeals from 16 parishes. On an average month, we may receive 80 writs from all of the 16 parishes. For the sinkhole incident, we received 255 writs,” says Judge Mitchell Theriot of Lafourche Parish, one of twelve judges that sits on the First Circuit Court of Appeal. A three-judge panel of the court typically hears thirty appeals from all sixteen parishes in one sitting. “This one incident produced eighty appeals. That clearly shows the magnitude and the volume of legal activity this one incident in Assumption

Remembering // Mabel’s House