The Houma’s Migration

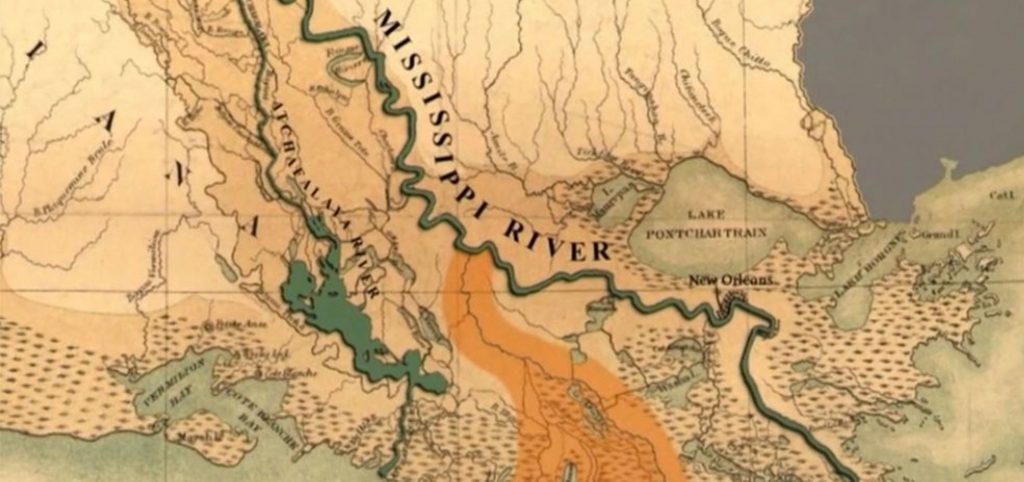

Family in a thatch palmetto camp. The Indigenous people of the delta House found near the New Orleans area. The Houma stayed alongside waterways while migrating for fertile soil and as a source of transportation. Houma Village in Baton Rouge 1699 Timeline of migration and first contact with western explorers. Image by Michael Dardar showing […]

The Houma People

By Jade Williams, features editor The native peoples who lived in North America are varied and plentiful. Just in Louisiana, tribes like the Chitimacha, Coushatta, Jena Band Choctaw were the first to make this land home. These tribes have an enormous amount of history. The tribe that eventually settled in the Bayou Region is the […]