Generational Perspectives

By Dylan Mcelroy, video editor The United Houma Nation is a tribe of Native Americans from South Louisiana fighting for their culture. Fighting to stay above water both metaphorically and physically. But why is their culture vanishing? Below are members of the community from different ages and areas. Listen to their stories of their everyday […]

Logo Symbolism

Environmental Threats

“Our people are having to leave because of land loss. A lot of them are not doing better for it.” – Thomas Dardar

Modern Migration

Many Houma families migrated to northern parishes such as Orleans and Jefferson Parishes in the 1940s-1960s for new educational and job opportunities. As the oil industry became a more valuable career option for them, many of these families migrated back to southern Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes in cities like Isle de Jean Charles and Dulac. […]

Modern Culture

By robbie trosclair, staff writer The United Houma Nation has an important and unique way of life. The culture they have been developing for hundreds of years has not been forgotten by them and instead has been cleverly adapted to and retaught in ways that match modern times. Areas like traditional jewelry, basket weaving, fishing […]

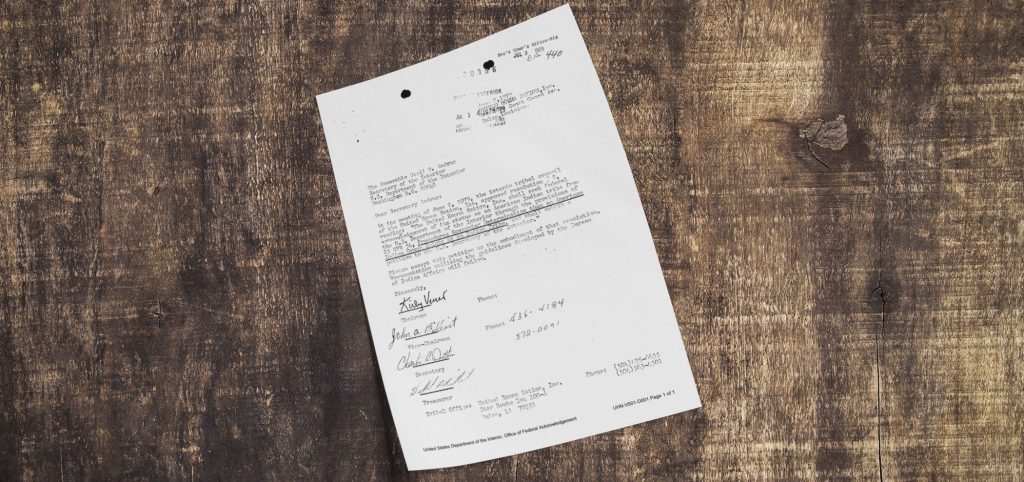

Seeking Federal Recognition

By Jade Williams, features editor The United Houma Nation is a tribe with over 19,000 members who have been recognized by the state of Louisiana, but have been fighting for years to get federal recognition. “We’ve been fighting for federal recognition for over 40 years. I don’t exactly know how long it could take, but […]

Membership

By brody gannon, staff writer Membership in the United Houma Nation is more than a title. It means more than the information printed on a tribal roll card. Becoming a member of the United Houma Nation is difficult, however. In 2014,tribal rolls were closed to all applicants over the age of five and the enrollment […]