Keyja Washington

Thibodaux, Louisiana Stayed with Family What has been the hardest part for you living through and after Ida? During the storm, I wasn’t sure if we were going to die. We heard the whistling of the wind, our windows were uncovered, and there were constant reports of damages. My younger siblings kept asking if we would die and I couldn’t give them a concrete answer. I just couldn’t. The hardest thing after the storm was losing power and internet. Just the world we live in, it’s hard to be so dependent on technology and electricity and not have it. It was hard to find out things going on. We had to use a radio. We also were struggling with our generator going in and out. It was also hard because I was in a house with a lot of people and we were all hot, bored, and miserable. It was hard to get what we needed. Just hard dealing with losing our house completely. And the rain after was so bad and it was hard to get help for that and to get people to come help with those damages. It was hard to deal with damages in general. My mom’s house wasn’t severely damaged, but still had roof leaks. What do you think is the biggest loss from Ida? The biggest loss from Ida has been the severe damages my grandma’s house now has. Also, being forced to live with other family members until the house can be fixed is a big loss. Listen

Jonathan Ricks

Hester, Louisiana Stayed What has been the hardest part for you living through and after Ida? We must have moved around five times while waiting for power to come back. Dad is on the older side and needs to do dialysis. He has a machine that lets him do that at home, but it needs power. For the first three days we were just trying to figure out how to keep him alive. Fortunately, my older brother got power at his house, so we were all able to crash there. What do you think is the biggest loss from Ida? For our family, it was our pecan tree. That thing was around before I was. The parts of roofing that are missing, the vehicles that were damaged, and all the mold can be fixed. A 60 foot pecan tree, however, is a bit harder to replace. Listen

Troy Dupont

New Orleans, Louisiana Stayed with Grandmother What do you think is the biggest loss from Ida? In my opinion the biggest loss from Ida was the down the bayou communities that were impacted the most. Not only did some of my friends lose their homes, but their stories were also uncovered by the national media. Listen

Emily Avet

Chauvin, Louisiana Evacuated to Houma, Louisiana What has been the hardest part for you living through and after Ida? The hardest part after Ida is not being able to go home; not being able to stay in my own home. What do you think is the biggest loss from Ida? The biggest loss is everyone losing their homes..the places we grew up in. Most impactful experience The most impactful experience I’ve had was helping at Ward 7 everyday; helping everyone in need . It was crazy to see how many other states donated to us. They gave us so much stuff from tissues, toilet paper, and napkins to feminine products and soaps and baby necessities, and so many can goods. Listen

Austin Avet

Houma, Louisiana Stayed What has been the hardest part for you living through and after Ida? There we so many homes that could’ve been saved if insurance companies would’ve worked more quickly and I think it correlates with the lack of media coverage for how slow everything is moving to help these people What do you think is the biggest loss from Ida? I believe the biggest loss from Ida would just be the amount of homes overall completely destroyed and the lack of help and media coverage as well as the lengthy process in which many people have to go through to fix or find new homes Listen

Alan Knight

Houma, Louisiana Evacuated to Toledo Bend, Louisiana What has been the hardest part for you living through and after Ida? Our people who will not rebuild or return. What do you think is the biggest loss from Ida? I think we will have lost many old but dangerous trees. As a result of an increased awareness of the dangers of water oaks, we will continue to have those trees disappear near homes. Listen

Jenna Beber

Reserve, Louisiana Evacuated to Morton, Mississippi What has been the hardest part for you living through and after Ida? The hardest part for me was knowing my friends and family were back home and there was nothing I could do to help them until the storm was over and the roads opened back up. The hardest part after was catching up with homework and trying to stay ahead in school and not fall behind in classes. What do you think is the biggest loss from Ida? For me, the biggest loss was my car. It’s getting fixed right now in the shop, but it did take damage from Ida. Listen

The Lost Bayou: Hurricane Ida

By Dex Duet & Mikaela Chiasson-Knight, Features Editor & Managing Editor Hurricane Ida, one of the costliest tropical cyclones on record, left a path of destruction from the Gulf Coast to the Northeastern United States, but it hit the Bayou Region of Southeast Louisiana first and hardest. “The only word I can use to describe it was terrifying,” says Houma resident Austin Avet. “The wind was so incredible that I could never tell if something was going to hit my house or if my roof would tear apart.” “The wind was so incredible that I could never tell if something was going to hit my house or if my roof would tear apart.” On August 29, the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina that decimated the Mississippi Gulf Coast and flooded New Orleans, this Category 4 storm destroyed the Bayou Region from Grand Isle to north of Lake Pontchartrain. With sustained winds of 150 mph, Ida tied Hurricane Laura in 2020 and the 1856 Last Island hurricane as the strongest storm to hit Louisiana, according to NOAA data. With the first alerts starting just three days before the Sunday landfall, meteorologists and public officials started warning of a very destructive hurricane and issuing mandatory evacuations for most parishes in Southeast Louisiana. “The reality is this part of the Louisiana coastline went many years without a major storm impact (Betsy 1965) so this was new for many people,” says Meteorologist Zack Fradella with Fox 8 in New Orleans. Ida was just shy of a Category 5 storm spanning from Port Fourchon to New Orleans, according to The Weather Channel. Port Fourchon, a local powerhouse for the oil industry, clocked winds of 228 mph and storm surge of more than 12 feet on one of their docked ships. The hardest-hit areas were the southern parishes: Terrebonne, Lafourche, and Jefferson. The eye of the storm passed right over eastern Terrebonne, while the worst part of the storm (the eastern eyewall) passed over northern Lafourche, devastating the community. Terrebonne Parish Police Officer Travis Theriot says he was on duty for hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Gustave and Ike and Ida was worse. “Twenty three years in law enforcement and that was the scaredest I’ve ever been in a storm,” he says. While some residents heeded the warnings and evacuated, many others, like Avet chose to stay. “I would never stay for another major hurricane because regardless of what the weather professionals say, you can never be sure how strong it can be until you experience it first hand,” says the Houma resident. Choctaw resident Aggie Thibodaux says the crisis became more apparent after the storm. “It all got worse when the storm ended and I found out that my friends were hiding in their attics,” says Thibodaux. After ploughing through Louisiana, Ida then turned north and tore through much of the South; even making its way to the Northeastern United States. The lingering power of the storm caused flash flooding in New Jersey where, according to Reuters.com, Ida claimed the lives of 50 people. For Southeast Louisiana, the storm has not passed. Even more than a month later, many residents are still without power and some are even living in tents next to their uninhabitable homes. Many people are still dealing with displacement, being out of work and struggling with insurance or FEMA claims, says Martin Folse, host of HTV Houma. “I’ve covered storms since 1985 and I’ve never quite seen a storm like this,” he says. “A lot of people are having a lot of struggle, but the vast majority aren’t struggling with the rebuilding as much as they’re being mistreated by their insurance companies and FEMA. That has been the most difficult thing in terms of recovery.” This semester’s Lost Bayou community truly chose itself. The entire region lost so much in this intense and deadly hurricane. Since our hometowns were brutally impacted; it is only right that we tell these stories: the stories of the storm, the stories of loss and the stories of recovery and resiliency. Our stories.

Generational Perspectives

By Dylan Mcelroy, video editor The United Houma Nation is a tribe of Native Americans from South Louisiana fighting for their culture. Fighting to stay above water both metaphorically and physically. But why is their culture vanishing? Below are members of the community from different ages and areas. Listen to their stories of their everyday life as a Houma Native American. Generational Perspectives Chad Pierre 47 from Grand Caillou Connie Fields 45 from Golden Meadow Kacie Fields 22 from Cut Off Kalob Pierre 17 from Houma Virginia Fitch 72 from Grand Caillou

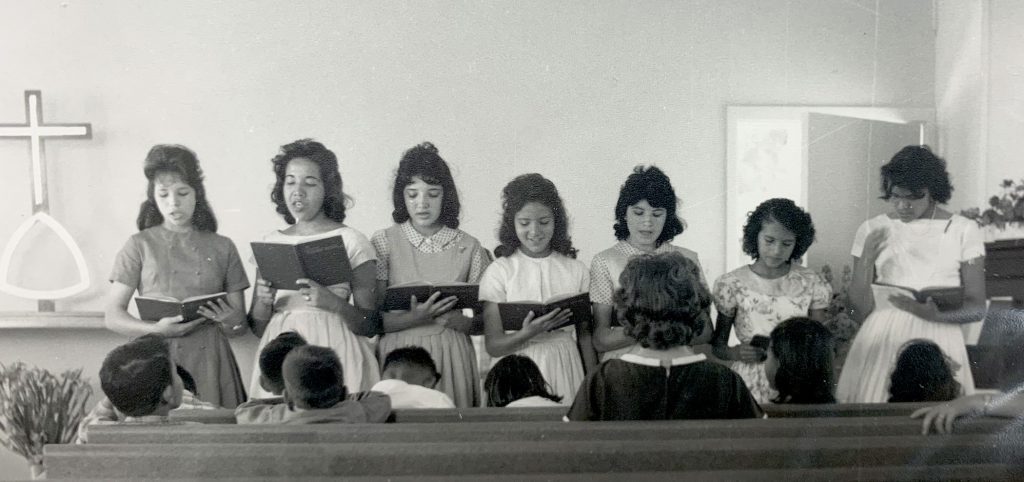

A Religious Spirit

By hannah orgeron, staff writer While the United Houma Nation’s traditional religious practices have mostly been lost over time due to the integration of Catholicism and Protestantism, religion is still an integral part of their lives today. Micheal Dardar, UHN historian, says the Catholic and Methodist religious practices were brought to the people by religious leaders and church groups starting schools. When the Indigenous people could not attend school, many Catholic and Methodist church communities fought to give them an education. When the Native Americans would attend the Catholic and Methodist schools, the teachers within the schools were teaching their religion and the citizens began adopting it. Father Paul Du Ru was the first person to start a Catholic Church within the Baton Rouge area. “Paul Du Ru stayed in the tribe ever since Catholics stayed in the tribe and he is especially relevant in the Grand Caillou community,” Dardar says. Ann Bolton of the Diocese of Baton Rouge, says Du Ru was the first person to hold a Catholic mass in that territory. According to the Native Heritage Project website, in the 1700s, Du Ru travelled with Iberville and instructed the Houma Natives to build the first Catholic church, St. Paul’s, in the Mississippi Valley in Bayou Goula, Louisiana in Iberville Parish. Du Ru eventually left to go back to Canada, but the teachings of Catholicism stayed with the Native people, who continued practicing Catholicism, passing the faith down from one generation to the next and replacing the old traditions. Helen Duplantis, a United Houma Nation citizen who works at the Southdown Plantation, says religion is very important in the area. “I grew up in a Catholic Church,” Duplantis says. “It was dominant in our area and we had a segregated church along the bayou. Our parents wouldn’t attend, but they made sure that we would.” Duplantis says her parents were more traditional and hadn’t fully adopted the Catholic religion, but wanted to make sure that the children got opportunities to go to church and have a sense of religion that was going along with their schooling. In the Dulac and Dularge areas, the Methodist communities started to evolve into larger groups. The religious leaders of the Methodist church noticed there was not a school system in place, so several started schools that evolved into a community center. The schools were employed by religious leaders who taught Methodists practices. As the children went to school, they started to adopt the Methodist religion into their lives. “Today a lot of people aren’t in the Catholic church, they are Methodist now and following the Methodist church,” Duplantis says. The Methodist religion was introduced by Rev. Anatole Martin in 1912, according to the document labeled Clanton Chapel. Anatole traveled across the bayou in a canoe to Bayou la Butte where a community of Houma families lived. This area no longer exists because in the 1930’s everyone started to move closer to the Dulac Mission Center. In order to be closer to the schools and the church community. The citizens of Dulac needed a place to hold services because they were taking place within residents’ small homes. According to another document from the United Houma Nation Archives, when Clanton met with the teacher of the Dulac Mission Center to see the work that was taking place, she and her husband decided to donate money to build the chapel. In 1936, the chapel opened and it served to fill the spiritual, social and physical needs of the people. Although previous generations had more traditional spiritual practices, the newer generations have adopted the beliefs and practices of non-natives, leading to the practice of modern day religions. PODCAST Tribal member Corine Paulk talks about religion and the United Houma Nation. Garde Voir Ci · Season 4, Episode 4 – Religion with Corine Paulk before and after clanton chapel in pictures The Dulac Indian Mission School helped give the Southeastern Louisiana Native Americans the education they deserve. Miss Ella Hooper and Mrs. George Deforest were sent to complete mission work with the Native American community in Dulac. They soon became concerned that none of the children were in school. Wanting to help in any way they could, they came together and organized a school for the community. For the first year they were holding classes in a dance hall, and then in April 1933, Miss Hooper purchased a plantation house that would soon become the Dulac Mission School. This school was a part of the four church-related schools in the area at that time. Although the schools were Methodists, they were still open to anyone regardless of their religious beliefs. (LSU) Miss Bessie Williams, an employee at the MacDonnells Methodist Center, reached out to her former Sunday school teacher, Mrs. Mattie Clanton, and mentioned that she felt the Houmas in Dulac needed a church building to have religious services. Mrs. Clanton and her husband wasted no time and donated the money that was needed for the chapel. The Chapel was named Clanton Chapel in the dedication of them in 1936. (Houma Chamber) Shortly after Miss Ella Hooper obtained her college degree in rural education at the Louisiana State Normal School, she had taken on a position at Terrebonne’s Cedar Grove School. She soon came to the conclusion that she wanted something different. She and fellow Methodist, Loura White traveled to the lower bayou communities in hopes to spread the Methodist faith. Once she made it there, she realized that there were bigger issues that needed to be taken care of. Hooper knew right away that establishing schools was the greatest need of the Cajuns and the Houmas. (J. Daniel d’Oney) In October 1919, the missionaries purchased a home that contained acres of property that would soon become the center of educational activity in Houma, this school. The Houmas main religion at the time was Catholicism; however, they soon realized they may have to convert to another religion if they wanted to receive an education. A hurricane