Cultural Blending // Vietnamese Culture

by Madison Boudoin, Staff Writer Many refugees of the Vietnam War found themselves in the Bayou Region of Southern Louisiana, surrounded by rich Cajun culture and opportunities for work. The journey across the world was tough and risky, but it is greatly appreciated by the young Vietnamese generation living on the bayou today. “It makes me feel grateful that I have the opportunity for a proper education and to pursue a career of my choice instead of having limited options,” says Tri Tran of Houma, whose family traveled from Vietnam to America. Refugees were limited to specific careers in America due to a language barrier and a lack of education. There were only a few options to choose from. Unlike his father, Tri has the resources to choose any career path that he wants. Tri’s father left Vietnam after the war, when the North began taking over the South. According to Tri, his father’s dream— a dream that was shared among fellow Vietnamese refugees— was to create a better life for himself and for his future family in the land of the free. Thanks to his father’s escape from Vietnam, Tri is now pursuing a degree in business administration at Nicholls State University. Tri says that the refugees came to America on over-crowded ships. Many did not survive the voyage. Disease and illness spread quickly aboard the ships because of the cramped living conditions. Other refugees were caught in dangerous storms and pirate attacks that left them dead according to the CBS Digital Archives. Brandy Vo, of Houma, says that her parents sacrificed a lot to come to America. “It makes me sad to think about the sacrifices that my family made to get here. They traveled across the world to a new location to make sure their future generations— my generation— would have a better life,” says Vo. The Vietnamese searched for jobs upon their arrival in America. Groups of refugees fled to the Bayou Region for job opportunities, as they had very little money and clothing. Refugees generally only spoke Vietnamese, so it was important to find work that did not require the English language. Many discovered careers in fishing, shrimping, and crabbing in the bayou’s seafood industry. This was also the best career choice for refugees who wanted to make a decent amount of money without needing an American education. “The reason why a lot of refugees chose this type of profession is because they didn’t really need to talk to get the job done. A lot of body language was used instead. They simply watched the Americans do the work, and learned the profession from them in that way,” says Vo. Vo learned Vietnamese from her parents as her first language. She didn’t learn English until she started Kindergarten. This made it difficult for her to fit in with the other children. “I got teased a lot. Thankfully they had a program at my school called ESL— English Second Language— and this was how I learned to speak English,” says Vo. Vo’s parents know very little English to this day. Her father is part of a fishing crew, and her mother works in a seafood packaging factory. Neither job requires fluency in English. According to Vo, Vietnamese families contribute to the seafood industry of the Bayou Region, which is an industry that will never go out of style in Southern Louisiana— an area known for so many authentic Cajun seafood dishes. Not only are the Vietnamese helping to keep the traditional Cajun culture alive through careers in the seafood industry, but they are also striving to preserve their own culture and traditions of Vietnam. Vo says that Vietnamese communities are smaller on the bayou than in other areas of Louisiana, and they tend to stick to the traditional ways of the Vietnamese culture. This includes practicing Buddhism. Chua Chan Nguyen is a Buddhist temple located in Houma, Louisiana. The temple serves as a place of worship for the Vietnamese communities in the area. People also gather at the temple to celebrate the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, the most important traditional celebration of the Vietnamese culture according to Vo. “The Vietnamese community on the bayou remains very old-fashioned. A lot of Vietnamese still cook the same traditional food that was cooked in Vietnam,” says Vy Truong, a student at Nicholls State University. Truong says that a few Vietnamese people on the bayou are slowly starting to break away from the traditional ways, but most are staying true to their culture.

Vacation Like a Local

by Lexcie Lewis, Special Sections Editor When summertime rolls around, locals head to their home away from home, Grand Isle. Louisiana isn’t known for having many beaches so whether it’s fishing, camping or just laying out by the water, the small island of less than 800 residents is the ultimate Cajun getaway. “I love coming here because even with a large family, everyone can be together the entire vacation unlike at a resort, says Elsie Dabie who has been visiting the island for over 20 years. “You can finally put your phones down and just enjoy each other’s company.” Grand Isle is a family friendly vacation spot where all the locals go. Large groups or families can rent a camp, which is just a house that’s on stilts to avoid flooding. While many local families own their own camps, others rent them out to locals and tourists. Camps can range from a two bedroom to an eight-bedroom house, which is perfect for large families. “I ended up coming for vacation and staying permanently,” says Ronnie Sampey, a Grand Isle resident of more than 35 years. “I eventually built my own camp and I rent it out during the summer.” Golf carts can also be rented and be used as the main vehicle. Grand Isle passed an ordinance in 2014 allowing people to drive golf carts on the road as a vehicle. Grand Isle Tourism Commissioner Louise Lafont says they’ve wanted to allow golf carts on the roads for a long time. “It’s hard for families, especially with small children to get from one place to another. Having golf carts makes it easier for families to load up the kids and go. The beach is across the street so you don’t have to lug your stuff back and forth.” Lafont says her main goal is to make everyone feel welcomed. She’s not originally from Grand Isle she grew up in Caminada, a town next to Grand Isle. She slowly fell in love with the island and is now a permanent resident. She says that she has a special place in her heart for every visitor, especially the “snowbirds,” or what locals call people from colder northern states that visit Grand Isle and become locals themselves. Twenty-three percent of the population was once a tourist that has since decided to stay. “No matter where you’re from you’re like family to me,” she says. “I’m going to treat you that way and I never forget a face.” Louise makes sure that having each guest that comes on the island sign a guestbook. This allows her to meet each guest personally and keep in touch with them beyond their stay. If a guest needs anything even just someone to talk to she’s right there. “My life is forever changed by these people.” She says. “I have friends from as far as Canada that have influenced me and made me love this job even more. Grand Isle is much more than just an island, it’s home to people for hundreds of years, people who have lived off the land and water, raising their families and creating a unique culture together. Grand Isle Tour Sources: Louise Lafont, Grand Isle Tourist Commissioner gave the history, traditions, and status of Grand Isle through an interview Welcome Louise Lafont, Tourist Commissioner, is preparing for Grand Isle to be considered for the Cleanest City. Mr. Norris, a resident, cleans the beaches year round. Bon Jour Walking into the Grand Isle Commissioner’s office, this is the first thing you see. Reflecting the attitude locals have towards all visitors. Drink the Wild Air, Swim in the Sea The guestbook, logging visitors from California to Canada. The Dome The butterfly dome is a safe haven for butterflies, with a donation box by the entrance for visitors to contribute. Coast Guard Station At the end of the Island is a Coast Guard Base. State Park Camping at Grand Isle State Park is a great alternative to renting a camp, it’s the cheapest way to vacation on the island, it offers clean bathrooms, and a starry sky at night. Pirate’s Cove Landing Gated communities are a frequent site. A Sneak Peak Looking through the gate, there are expensive boats and million dollar camps that are only occupied half the year on average. Blue Moon Over Grand Isle Renting out camps is a common practice for those who don’t stay year round. Beach Apartments An alternative to renting a camp. Hurricane Hole Restaurant The fancy restaurant on the island. Hurricane Hole Hotel The camp feel, with hotel amenities. Presidential Palace You and 20 of your closest friends will have a presidential experience. A Boat Riding Bayside Driftwood Throughout history, Grand Isle residents have carved their initials into pieces of driftwood they want to claim. Others then know not to disturb the driftwood and that it’s already spoken for. What’s Left Some never rebuilt after Katrina hit. Island Mardi Gras Stored busses and floats for Mardi Gras is an ever present reminder of the attitude of locals have- laissez les bon temps rouler. Beach Access There are 19 public points of entry to the beach up and down the island. Watching Birds Birdwatching is a common activity, with the Grand Isle Migration Celebration in April. Jetties In an attempt to prevent erosion, rock jetties have been placed off the coast. It has been successful so far as it has changed the current, and planning has begun to place them all the way up the island.

Bayou Sleeps // Unique Places to Stay

By Cullen Diebold, staff videographer

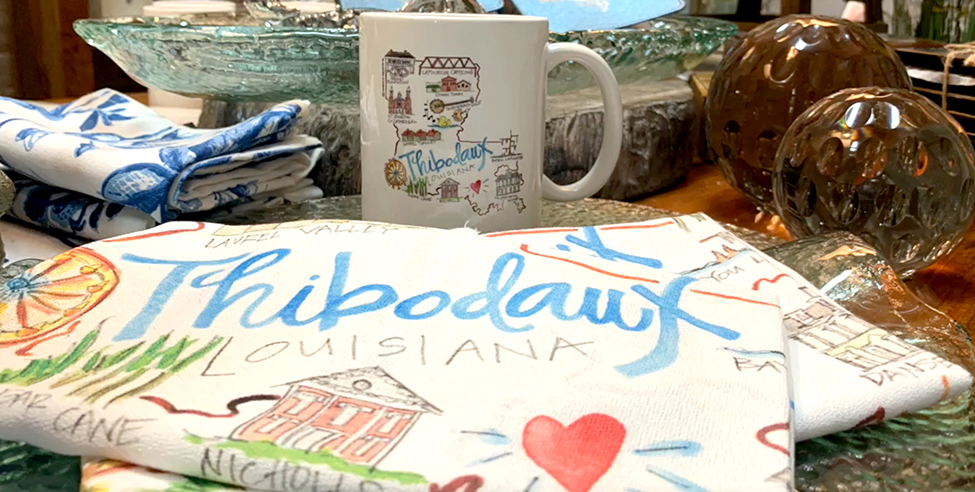

Bayou Souvenirs // Unique Gifts

by Brandy Dunbar, staff videographer

Up The Bayou vs. Down The Bayou

Making Music // Recording Studio

by Ashlyn Verda, staff writer Hidden in the quaint suburbs of Houma, Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions serves as an essential recording studio for musicians in the Bayou Region. Pershing Wells— a professional guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter from Bayou Black— owns Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions, where he works with local songwriters to develop their music into tunes that are ready for the radio. “I’m the guy they come to locally,” says Wells. “I’ve produced about 75 albums and more than 1200 songs.” Since the studio’s opening in 2002, Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions has helped professional musicians with producing and recording their songs. The studio also offers guidance with the mastering and arranging of songs. “When you arrange a song, you’re basically taking all the musical elements and reordering them and changing the sounds you hear in order to create a unique experience,” says John St. Marie, a musician, conductor, and educator at Nicholls State University. Wells says he enjoys the process of figuring out where he can take a song. However, he’s cautious about repeating arrangements for different clients. One of his main goals is to discover the different ways he can capture the uniqueness and originality of a song. To find that originality, Wells likes to hear clients perform their song with just an acoustic guitar and their voice. While listening, he’ll usually find a tempo that matches the song. “I think I have a very good talent for hearing what they are trying to do—the feel of the song,” says Wells. After hearing the barebones version of a song, Wells begins arranging and composing the rest of the instrumentals. Although he creates most of the instrumentals digitally, Wells sometimes brings professional musicians and session players. These musicians are usually keyboardists, guitarists, violinists, fiddle players, and steel guitar players from the Bayou Region. “My favorite thing is watching a client listen to their song after it comes to life for the first time,” says Wells. “I’ve seen some tears and I’ve seen some beautiful smiles. Nothing beats it.” Most of Wells’ clients are local. Veteran singer, songwriter, and bassist Tim Dusenbery worked with Wells on his 2004 record Kingdom Come. “It’s been a desire of mine to express myself through music,” says Dusenbery. “I heard great things and decided to team with Pershing to complete the album. The recording process went smoothly and I don’t know how I would have done it without him.” Wells began playing music at 14-years-old, when his eldest brother Bill brought home a Sears Magnatone guitar. He started playing by ear and developed the skill quickly. After jumping between a couple local bands, Wells moved to Colorado and became a full-time musician. “Like everybody else, I was hopeful that some break would happen. I took it as a five year musical sabbatical, during which I continued to hone my musicianship,” says Wells. Wells eventually moved back to Louisiana to start a family. Locals knew him at the time as a guitar player, rather than a producer. After taking a year off from playing music, he joined the Country Sunshine Band. From the 80s to the mid 90s, Wells featured as a session guitarist in dozens of local “Swamp Pop” singles and albums. He also performed multiple times at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. While working as the chief engineer at Houma’s Apple Tracks Recording Studio, Wells released his first CDs as a producer. At Apple Tracks, Wells taught himself how to professionally record and produce music. After being laid off from Apple Tracks, Wells began recording with his brother, which evolved into recording a full album. From that point forward, Wells received a steady flow of calls from clients asking for help on their albums and songs. The influx of requests made Wells realize that he didn’t have time for a day job. By 2005, he had a waiting list of clients and was able to place his recording studio next to his home. By helping local artist with their careers, Wells has contributed to keeping cajun, zydeco, and swamp-pop music styles alive in the Bayou Region. Some local favorites Wells has worked with include Don Rich, Joe Barry, Southern Cross, and Tab Benoit. The music by these musicians and other local legends can be found at Fabregas Music Store in Houma. These days, Wells, in addition to recording and producing for local artists, still finds time to tour and play live with his friends. Visitors to the Bayou Region can catch him at seasonal festivals, The Balcony Bar, and On The Canal Bar, where he regularly plays. Even though Wells has become successful enough to move away from Houma, he’s decided to stay. “A lot of people ask me how come I don’t go to Nashville,” Wells says. “I’m content here. I feel that I’m a resource that is needed in this area.” For more information regarding Digital Sac-a-Lait Productions, contact Pershing Wells at http://www.pershingwells.com/digital_sac_a_lait_productions.htm.

On the Water // Paddle Bayou Lafourche

by Wes Barnett, staff videographer

Sweet Finishes // Cajun Desserts

by Kaitlyn Biri, photo editor

Cajun Food Fails

by Hannah Grigsby, staff photographer

A Different History // Whitney Plantation

by Trevor Johnson, features editor Southern plantations have long been tourist stops for curious travelers from around the world — most offering wedding services, detailed accounts of wealthy slaveholders, and cheap memorabilia. However, Whitney Plantation, located in Wallace, LA, breaks the mold by giving an unflinching look into the lives of its former slaves. “Our mission is to tell the story of the enslaved people,” says Joy Banner, the director of communications at Whitney Plantation. “Other plantations talk about slavery, but we are the only plantation museum with an almost exclusive focus on slavery.” Whitney Plantation stands on a grassy plot of land near a levee of the winding Mississippi River. Visitors can walk the grounds through a guided tour, Whitney’s main attraction. The tour, which has a variety of admission prices, lasts about 90 minutes, and gives visitors the opportunity to explore slave quarters, a church, a historical blacksmith’s workshop, and more. The tour also includes visiting a memorial to the slaves who worked the plantation. “In addition to telling the history of slavery, Whitney Plantation serves as a memorial to the slaves who worked here, which can be a painful subject,” says Sydnee Council, a tour guide at Whitney. “Some people cry. Some people get angry.” Statues of enslaved children, creatively depicted as they would have appeared on the day of the plantation’s emancipation, dot the grounds in various locations, such as sitting in church pews, or perched solemnly on the porch of a slave cabin, their dangling legs forever captured mid-swing. Over the course of the tour, their unblinking gaze forces visitors to confront one of America’s greatest wounds. After the tour, visitors may keep their tour pass. Each tour pass contains a unique account from one of the slaves who worked the plantation. Whitney also offers a free exhibit, which details the general history of slavery in America, inside its main building. Although plantation tourism may seem like a modern affair, plantations have received tourists since the 1800s. “Plantations became a tourist destination as early as the 1830s,” says Stuart Tully, a history professor at Nicholls State University. “There were grand tours going around the South, with visitors from Europe and elsewhere. Even when they were working plantations, there was a small element of tourism.” According to Tully, plantation tourism dipped during the Civil War, and wouldn’t fully return until around the 1930s. The version that returned, with the veneration and reverence of “Southern heritage,” is the version that is most recognizable today. “It came back because of financial necessity, coupled with the lost cause mythos,” says Tully. “The idea that you’re buying into this idea of the Antebellum South, with Spanish moss, and fans, and ladies. That’s when you really start getting into the imagined past. They saw imagining the past as profitable.” Whitney Plantation aims to dispel the “imagined past” of Southern plantation culture, most commonly depicted in the film Gone with the Wind. Although the plantation has stood since 1752, it was bought by John Cummings in 1999, who, according to Banner, began transforming the plantation into the institution it is today. When Cummings bought the plantation, he also received several volumes of research. That research, combined with his reading of slave narratives, inspired Cummings to craft an educational experience focusing on the lives of slaves. After about 15 years of restoration, Whitney Plantation opened its doors to the public as an informative journey through the lives of America’s most forgotten voices. “People want nostalgia,” says Banner. “We don’t do nostalgia at Whitney Plantation. That’s a fantasy. That’s a fairy tale.” For more details about Whitney Plantation and their tour, visit https://www.whitneyplantation.com/.