An Island Timeline

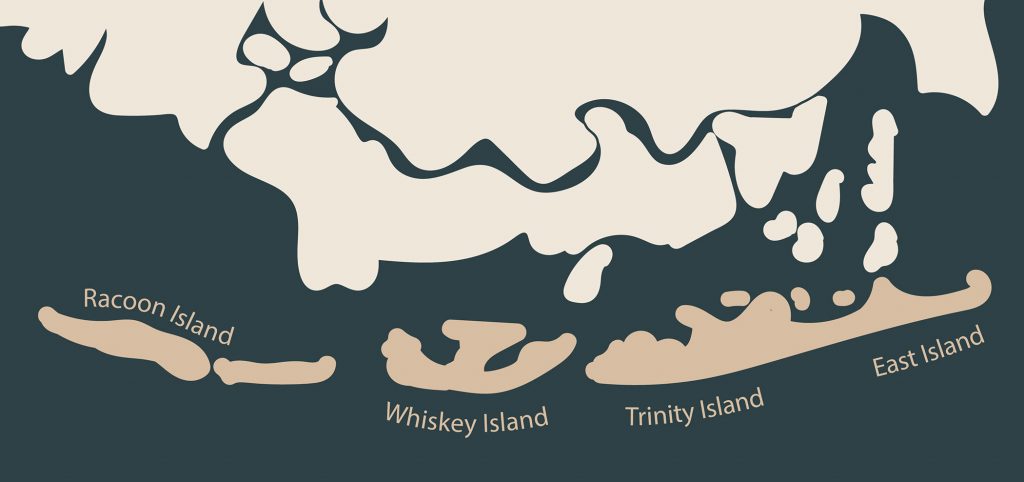

a timeline Isle Dernière 1800 Untamed Land A raw, natural island oasis 1830s Rustic Getaway Small fishing huts existed on the island. 1840s Land Purchased Developers began to purchase land from the US government. 1848 Resort Established The four Muggah brothers along with financers from St. Mary Parish developed the Ocean House Hotel. 1856 Bigger Plans Plans were made by the four Muggah Brothers, along with the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans, to begin construction for a bigger, more elaborate hotel dubbed the Tradewinds Hotel after the summer season in 1856. August 10, 1856 The Great Storm A category 4 hurricane destroyed the entire island, breaking it into four islands — Racoon, Whiskey, Trinity and East. Today Protected Wildlife Area Most of the islands is protected for sea birds and other wildlife.

The Island Today

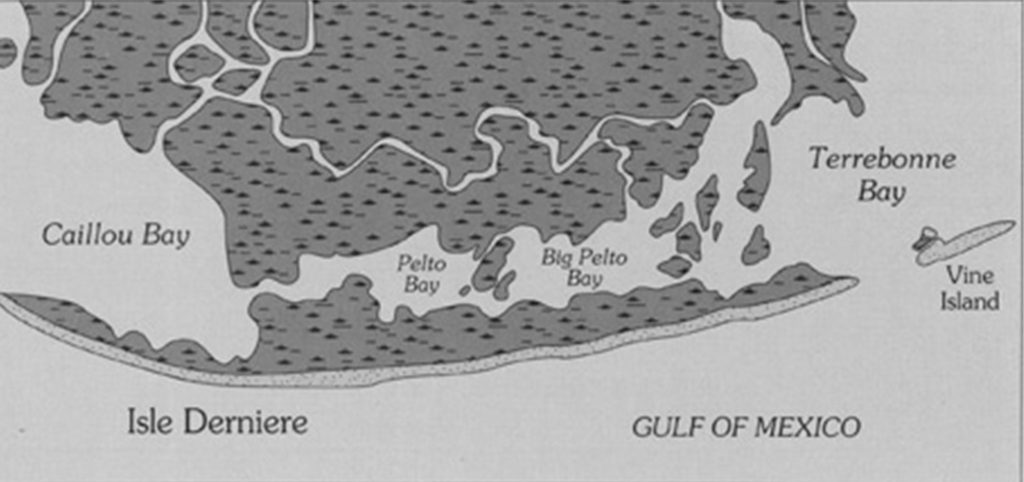

By Kia Singleton Photo Editor After the 1856 hurricane that destroyed the resort of Isle Derniere, all that was left on the island were seabirds. Over time, the remainder of the island was separated into five smaller islands known as the Isle Dernieres Barrier Islands. These barrier islands are Wine Island, East Island, Whiskey Island, Raccoon Island, and Trinity Island. Now owned by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, the islands are mostly protected space for waterbird nesting. But a portion of Trinity Island, the island farthest east of the Isles Dernieres chain, is accessible for public use. People can picnic, fish, camp overnight, and bird watch in permitted areas, according to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. While the activities on the island are restricted, the waters surrounding the barrier island refuge are a popular recreational fishing destination. Mr. Lance Schouest, also known as Captain Coon, is a Tour and Fishing Guide at the Tradewinds of Cocodrie, which is a marina and lodge northeast of the Isle Dernieres Barrier Island Refuge. During a phone interview, Schouest said, “It’s a pleasure to see people catching fish and seeing the enjoyment on their faces, and that makes getting up at 4:30 in the morning to work in the heat worth it.” He also explained that he takes all his customers to areas where the fish are most active. He said, “The fish are always biting.” Trinity Island has more human activity than any of the other barrier islands. On Trinity Island, people can travel by foot or by bicycle. The use of ATVs or other vehicles with engines or electric motors are not allowed on the island. Firearms, fireworks, and explosives in the public area are not allowed. To utilize the public area, a visitor must have a portable waste disposal container for human waste. This means there are no restrooms on the island. No one can disturb, injure, or collect plants and animals. Fishing from boats is allowed as well as wade fishing in surf areas. Boat traffic is allowed in open waters, like gulfs or bays, and within the California Canal. However, no boat traffic is allowed in any other man-made or natural waterways that extend into the inside of the island. Boat traffic is also not allowed in land-locked open waters or wetlands. Captain Paul Titus created a GPS tool with coordinates for fishing spots near these barrier islands. These spots are called waypoints. According to an article from LouisianaSportsman.com, “Captain Paul’s Fishing Edge of GPS Waypoints of the Cocodrie-Dulac area is located from Point au Fer Island, Four League Bay to the east of Cocodrie from the Gulf of Mexico by Isle Dernieres to Lake De Cade by Bayou DuLarge.” This is the southern part of Terrebonne Parish. A location between Whiskey and Raccoon Islands is known for being a great fishing spot; the coordinates are 29 degrees 02.9948’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 52.7825’ W. Longitude. There is also a U.S. Geological Survey Benchmark for “Coon Point”. At one time, this was western part of Raccoon Island. The coordinates for Coon Point are 29 degrees 03.5490’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 57.6655 W. Longitude. Between Trinity and East Islands is a waypoint with deeper waters than any other locations in the area. The coordinates are 29 degrees 03.7278’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 41.5423’ W. Longitude. A location known as “Horseshoe Reef” is said to be a popular summer destination. It is in the northwest part of Trinity Island, which is east of Whiskey Pass. The mouth of the cove at Horseshoe Reef coordinates are about 29 degrees 03.395’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 44.521’ W. Longitude. Trinity and Raccoons Islands are more accessible than Whiskey, East, and Wine Islands because of the bird habitats, the designated public areas, and the abundance of fish. Most of these areas are occupied simply by fishermen. If someone would want to spend time on the barrier islands, filing the correct paperwork with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries is imperative. a little Island Fun Check out the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries for more information on access to Isles Dernières. More Information Island Activities birding picnicking fishing camping PODCAST Dr. Quenton Fontenot, professor and head of Biological Sciences at Nicholls State University, discusses the barrier islands today. Garde Voir Ci · Season 3, Episode 4 – Isle Dernière Today with Dr. Quenton Fontenot

Island’s Long-Battled Ownership

By Payton Suire Managing Editor Eight years before Last Island was destroyed by a hurricane, the Voisin family began a land dispute that wouldn’t end for almost two centuries. In 1848, people began to question who owned Last Island when the State Land Office began selling tracts of land on Isle Derniere. Jean Joseph, J.J., Voisin, son of an eighteenth century French immigrant, confronted the purchasers, Thomas Maskell and James Wafford insisting that his family owned the island, which had been in the family for 70 years, by a 1788 Spanish land grant. In the Public Land Claims, it says “a Juan Voisin, una pequeña ysla, vulgarmente llamada L’Isle Longue . . .” (“to Jean Voisin, a small island, commonly called L’Isle Longue . . .”). The claim describes the location of Isle Longue as “situated in the Lake of Barrataria, adjoining (or contiguous to) on one side Last Island, and on the other, fronting the island called Wine Island.” On July 1, 1833, J.J. Voisin submitted documentation for claims on two tracts of land: Pointe-à-la-Hache and Isle Longue. A neighbor, Charles Carel, someone well-acquainted with the island, made an affidavit, “it has always been in his [Voisin’s] possession or in that of those who held it for him,” The 1788 order of survey and testimony supported Voisin’s two claims. In 1835, Voisin made another claim to the land when the U.S. Congress enacted legislation confirming the original grant, according to Public Land Claims Number 4533. In November of 1837, Gilmore F. Connely, a deputy surveyor, contracted with the State Land Office to survey portions of Terrebonne Parish, including “all the islands on the coast.” Four years passed before the surveys were certified, and two years later in 1844, the State Land Office added a second annotation to the west end plat. Last Island was for sale, according to the Last Island Survey Plats. The increased demand for land on the island corresponds to the “discovery” of the island’s sandy, white beaches. By 1846, steamboats and sailboats regularly took visitors to the island. Some began constructing cottages or summer homes along the beach. Last Island’s popularity spread, and on April 8, 1848, St. Mary Parish sugar planter, Thomas Maskell, purchased 160 acres for about $200, worth about $6,600 today, according to the Bethany Bultman Papers about Isle Derniere. On July 13, 1848, James Wafford purchased 53 acres west of Maskell. When confronted by Voisin, one purchaser, Alexander Pope Field, used a military warrant to claim his 100 acres and a Louisiana Surveyor, Gen. R. W. Boyd for a ruling. Boyd explained that in his office’s survey of Last Island, there was no survey or knowledge of Isle Longue. In the Public Land Claims, Voisin’s lawyer, F.C. Laville, questioned when he could expect to receive his patent but went months without reply. Boyd finally replied stating an island named Isle Longue “has not yet been surveyed.” This explanation failed to impress Laville who explained the name of Isle Longue had changed over time to L’Isle Derniere or Last Island, but the argument failed. The dispute intensified when Voisin moved his family to Last Island in 1849. In 1854, Wafford’s attorney filed suit in Houma to evict Voisin from his property and assess the damages from his actions. On November 28, 1854, Voisin’s attorneys filed a civil suit countering the claims of Wafford declaring Voisin to be the “true and lawful owner” of an island “wrongfully” called Last Island. They presented three documents: the 1788 Order of Survey, the Register’s recommendations, and the 1835 Act of Confirmation and asked for 3,000 dollars in damages, about 93,000 dollars today. As the chaos and contradictions ensued, the 1855 court calendar came to a close with each side eager for a winter break from court proceedings. The judge announced the case would resume in 1856 — the year the Last Island Hurricane hit. “Within weeks, the slow-moving trial would be upstaged by another slow-moving presence, a large counter-clockwise cloud formation stirring in the eastern Gulf ofMexico. A huge storm was inching slowly toward Louisiana’s central coast,” according to The National Hurricane Center (NHC) the Atlantic Hurricane Database Reanalysis Project. “After the storm, I think he just lost interest in it,” said Jeanette Voisin, a descendant ofJ.J., in an article by Houma Today, who is fighting for the land rights. “Everyone died out there. No one wanted to go back.” According to the book “Last Days of Last Island,” South Louisianians lost interest in the ownership of Last Island in the storm’s aftermath. The entire village was washed away in one afternoon leaving the trial to end gradually. In 1859, a judge postponed the case indefinitely due to the parish being invaded by the North as the Civil War ensued. After the Civil War, the dispute was reopened one final time, but most of the litigants and witnesses were dead, old, sick or weak. The judge placed the trial on a “dead docket” constituting neither a dismissal nor termination of the case in which it can be reinstated at any time. The file of documents, testimonials, and maps would remain untouched for generations. Flashforward to 1988, James Voisin was gathering information for the Voisin family tree when he found a spotted, faded brown pocket folder with a file titled “Jean Joseph Voisin versus James Wafford, et al.” He recalled a story his father, Everett Voisin, told him. During the ’50s and ’60s, Everett Voisin operated crew boats in the Atchafalaya River Basin when a coworker showed him an offshore drilling map with the name “Voisin” penciled along a small island situated in the middle of Isles Dernieres. Everett never pursued the information. Who Owned Last Island? Solving a Centuries-Old Louisiana Puzzle. Twenty-five years later, James Voisin shared the story with the rest of the family, which, after months of discussion, decided to engage an attorney. In late 1989, Lexington attorney Tim Hatton wrote to the Bureau of Land Management on behalf of the Voisins. “Jean