Coastal Restoration

By Kelsi Chapman, Podcast Editor

Island Water Quality

By Brittany Chaisson, staff writer Much of Louisiana’s coastal waters are polluted, but Grand Isle’s location at the mouth of the Mississippi River and its human inhabitants make its waters particularly susceptible to contamination. Experts say that agricultural runoff and marine debris are the leading cause of water pollution on Grand Isle’s coast. “The thing […]

Hurricane Ida

By Alaina Pitre, staff writer Being on the front lines of the Gulf of Mexico, hurricane season is especially busy for Grand Isle with evacuation almost always mandatory. While many hurricanes have impacted the island, Category 4 Hurricane Ida was one of the worst to hit Louisiana’s coast and directly hit Grand Isle. The storm […]

Grand Isle’s Hurricane History

grand isle hurricanes 1855-present By Alaina Pitre, staff writer As a barrier island, many storms have hit Grand Isle. The following are a list of major hurricanes, categories 3-5, that have affected the island since 1855. 1855 Category 3 Unnamed Winds: 125mph 1856 Category 4 Last Island hurricane or Great Storm of 1865 Winds: 150 […]

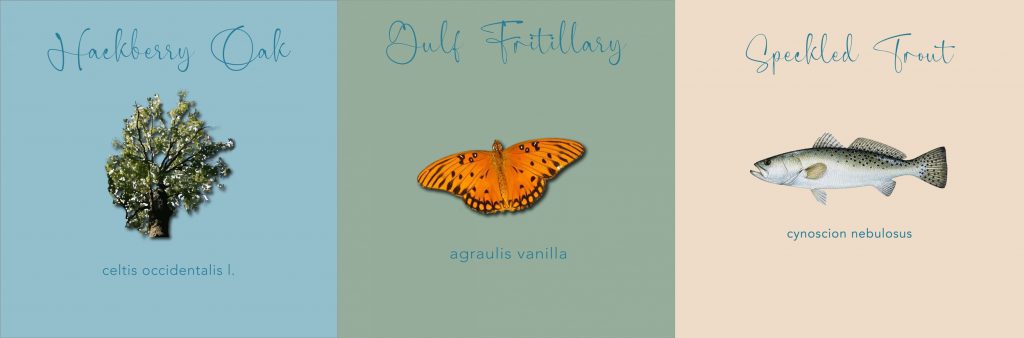

Island Flora & Fauna

by Brittany Chaisson, staff designer

The Island’s Environment

by Alexis Casnave, staff writer While many people enjoy Grand Isle’s natural beauty, it doesn’t exist without threats from factors such as storm damage. The community of Grand Isle works diligently year-round to ensure the island remains alive and well. “The work being done on Grand Isle is through the efforts of the town, the […]

Island Storms in the Media

Gathered by Victoria Savoy, photo editor Hurricane Ida is not the first, nor will it be the last storm to hit Grand Isle. As a barrier island, Grand Isle has been the target of many storms through the years. National and local media have covered these storms, leaving a record to tell the story of […]

Storm Stories

A podcast series about hurricane experiences on Grand Isle.

An Inland Barrier

By Jonathan Eastwood , Features Editor Inland South Louisiana communities like New Orleans owe a lot to barrier islands like Grand Isle. “[If] Grand Isle goes, Bourbon Street’s gonna have eight feet of water,” Grand Isle Mayor David Camardelle says. “It’s coming.” “[If] Grand Isle goes, Bourbon Street’s gonna have eight feet of water. It’s […]