Finding Grand Bayou // Mislabeled Waterways

By Chakyra Butler, Staff Writer With only a few abandoned buildings left in Grand Bayou, it can be a difficult place to find. An internet search for Grand Bayou, Louisiana, pulls up a community in North Louisiana near Shreveport. And when the area is finally found on a map, Google Maps has mislabeled the area’s waterways — once the center of the vibrant community. Online, the waterway along Highway 69, near Highway 70, is labeled as Avoca Island Cutoff. That bayou, along with many other surrounding waterways, are all mislabeled with that same name. Some former residents of Grand Bayou were not even aware of the bayou being incorrectly named. “I don’t know why it’s like that,” says Nicki Boudreaux, whose maternal family is from Grand Bayou. “We talked about calling Google and having them fix it.” Former resident Jerry Rousseau says he did not know Grand Bayou was mislabeled until it was recently brought to his attention. He said the bayou and the canals go to Lake Verret, not the cutoff. “So, Avoca Island is definitely not right there,” Rousseau says. “It’s just mislabeled.” Rousseau says his property, the Hebert property, in Bayou Corne is mislabeled at Assumption Parish Assessor’s Office. The real Avoca Island is located south of Morgan City and off the Intracoastal Waterway in the Morgan City bayous. It’s bay, Avoca Island Cutoff, is more than 40 miles away from Grand Bayou.

A Gas Leak // The Evacuation of Grand Bayou

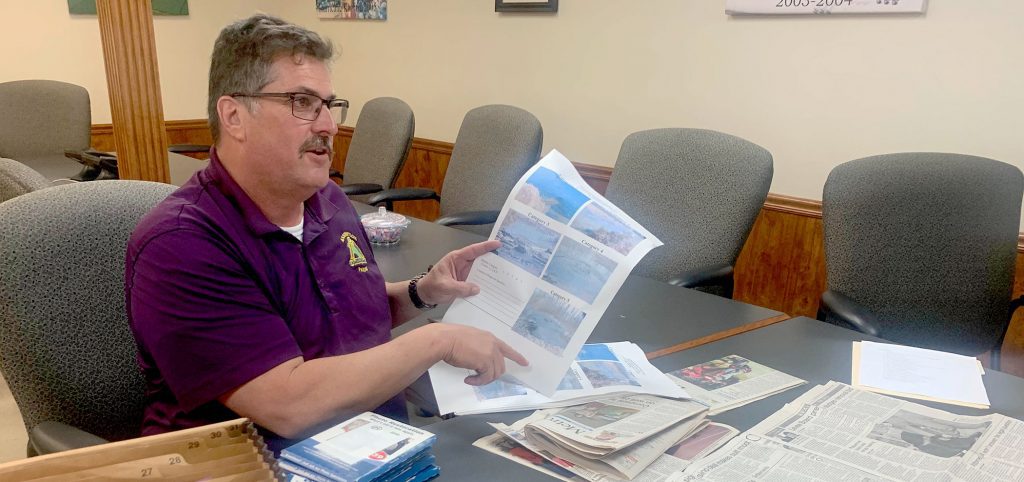

By Emilee Theriot, Staff Writer Christmas is a time to spend with loved ones, a time of giving and a time to make new memories, but for John Boudreaux and the Grand Bayou community, Christmas of 2003 was anything but festive. As the director of the Office of Emergency Preparedness for Assumption Parish, Boudreaux was the person who received emergency calls for the parish. So to get a call about a brine leak from Dow Chemical, which had been operating in the area since 1956, was normal. Except it was Christmas Eve. And when he got to the Grand Bayou Dow Chemical facility, water was jetting 20 feet into the air. “It sounded like a jet engine. It was an ‘oh shit’ moment,” Boudreaux says. Company representatives first thought it was a brine leak and later deemed it a natural gas leak, Boudreaux says. Natural gas has no smell, so it is difficult for the average person to know if they are in danger and it’s hard to know what’s causing the leak. But Dow Chemical did note that Gulf South had natural gas pipelines in the area. Boudreaux says he met with Vernon Self, a Gulf South representative, at the site and asked about the cause and the extent of the gas leak. Without an explanation from Self, Boudreaux eventually left the site and instructed Gulf South to call if it got worse. On Christmas morning, Self called, and Boudreaux returned to the site. Boudreaux’s phone rang again, this time it was Nolan Blanchard, a Grand Bayou resident, calling to say the ground in and around his yard was bubbling. Boudreaux immediately rushed to Blanchard’s home with his air monitoring equipment, and he picked up a slight hint of a lower explosive limit on the monitor. “This ain’t good,” Boudreaux says he thought to himself. Boudreaux then called Marty Triche, the president of the Assumption Parish police jury, to inform him that residents needed to evacuate. Boudreaux said he knew it would not be a popular decision, but the safety of the public was his number one concern. “It was the toughest decision I ever had to make,” Boudreaux says. Residents were told late Christmas afternoon they had four hours to evacuate. Residents were also notified that Louisiana Highway 70 would be closed at 10 p.m. Arrangements were made to house the residents at a local hotel near the Sunshine Bridge. Twenty-eight residents evacuated to the local hotel. Tracy Scioneaux, 30 at the time of the gas leak, says she was celebrating Christmas with her family at her mother’s house when a volunteer firefighter friend told them they were planning to evacuate the residents of Grand Bayou. “My mom always told us something’s going to happen here.” Scioneaux says. “We had to pack up all our food and bring our presents we had just opened and some that we didn’t.” The evacuation lasted 52 days. Scioneaux says the days were hectic at first. Gulf South plugged rigs into the salt cavern and dug them into the water aquifer to allow gas to escape and reduce the pressure. Gulf South found a crack in a casing that went down to the salt cavern, causing too much pressure. Boudreaux says he kept the public informed the best he could. At one point there were five state agencies on site: Department of National Resources, Department of Environmental Quality, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Louisiana State Police and the governor’s office. On the local level, there were representatives of the sheriff’s office, OEP and the fire department. Gulf South, Dow Chemical and the various rig companies were also on site. Boudreaux and company officials briefed the evacuees every evening at the hotel. Scioneaux says Gulf South officials did their best to answer their concerns. Boudreaux adds that while friction between company officials and public officials rose, they all continued to work together to resolve the situation and accommodate the public. A public meeting was scheduled for Jan. 13, 2004, at the No Problem Raceway lounge. The crowd was so large, makeshift bleachers were erected outside to accommodate the several hundred people that showed up. Public officials also followed up with fliers updating the progress throughout the ordeal. “They did a really good job on taking care of the people,” Scioneaux says. “They took responsibility.” Gulf South paid for the evacuees’ food and lodging at the hotel. After a period of time it was agreed by Gulf South and the evacuees that Gulf South would start paying an allowance rather than pay the hotel bill, giving evacuees an option of where to stay. Scioneaux’s family rented a house in Napoleonville with her brother’s family. Gulf South also paid for people to clean the evacuees’ homes prior to moving back. After moving back to their homes, Scioneaux and her husband, along with all the other Grand Bayou residents, were approached by Gulf South to purchase their home and land. “The older people didn’t want to leave, but eventually, everyone sold their houses and moved from Grand Bayou,” Scioneaux says. “It was a change of life.” “We don’t blame the companies because without companies we wouldn’t have a livelihood,” she continues. “But, it was disheartening knowing that on Christmas Day that happened in 2003 and my mom died in 2005, so toward the end of her life this is what we had to go through.” Natural Gas Vent Vent well installed in Grand Bayou to vent the gas from under the property. The Assumption Pioneer, February 19, 2004 The Assumption Pioneer, February 19, 2004

Natural Resources // Grand Bayou’s Salt Domes

By Emilee Theriot, Staff Writer In addition to a bounty of fish, animals and plant life above ground, the earth beneath Grand Bayou is rich with natural resources like salt domes, natural gas and oil. “Wherever you have a salt dome, somewhere along the line there is oil and gas,” Jerry Rousseau, a Grand Bayou resident, says. The first salt dome in Assumption Parish, which became known as the Napoleonville Salt Dome, was discovered in September of 1926, according to a 1927 article in The Assumption Pioneer. The largest of the 68 salt domes discovered in Louisiana, the Napoleonville Salt Dome was about one mile by three miles. It began at 700 feet below the surface and went to a depth of 30,000 feet. Dow Chemical began purchasing the land above and around the salt dome in 1956, according to the conveyance records at the Assumption Parish Clerk of Court office. The company purchased 103 acres from Schwing Lumber, a large landowner in the area, and 169 acres from the Leblanc family as well as several hundred acres from dozens of families. Each act of sale included language that the sellers reserved a five-cent-per-ton royalty from the sale of the salt removed from the dome. Dow wanted the salt domes to use the brine in making plastics in their chemical plants along the Mississippi River, Rousseau says. To mine the salt, the company drilled a well in Grand Bayou and pumped hot, fresh water into the salt dome, which eroded the salt from the dome, says John Boudreaux, the director of the Office of Emergency Preparedness for Assumption Parish. The mixture of the fresh and saltwater created a solution called brine. A second well was drilled from above ground and entered the new salt cavern to retrieve the brine. The brine was pumped out of the salt cavern into above-ground storage tanks. Once above ground, the brine was shipped by truck to the Dow Chemical plant in the nearby city of Plaquemine in Iberville Parish. The plastics produced using the brine were shipped from the plant along the Mississippi River to various other plants throughout the United States. The plants would then use the various plastics to make consumer products like toys, paint and appliances. This system worked for many years. But as salt was removed from the dome,it left an empty cavern within the salt dome, Boudreaux says. And a typical cavern is the size of 50 Mercedes Benz Superdomes — underneath homes and communities. Then in the 1960s and 1970s, various oil companies leased the caverns from Dow Chemical to store oil and gas. With the dome so big, Dow allowed Texas Brine to begin extracting brine from the Napoleonville Salt Dome in the 1960s. Rousseau’s father was the first employee at the Texas Brine Grand Bayou facility. “My dad’s job was to make sure the plant was run correctly,” Rousseau says. “Trucks would come in and pump the brine into the tanks and bring them where they needed to go.” Now, most of the brine is transported via pipeline. Brine continues to be removed from the salt dome and delivered to chemical plants along the Mississippi River in Taft, Geismer, Gramercy and Plaquemine. The more brine removed allows for more oil and gas to be stored. Today, there are over 60 caverns located in the Napoleonville Salt Dome. Boudreaux says a few more permits are pending to develop more caverns in the Napoleonville Salt Dome.