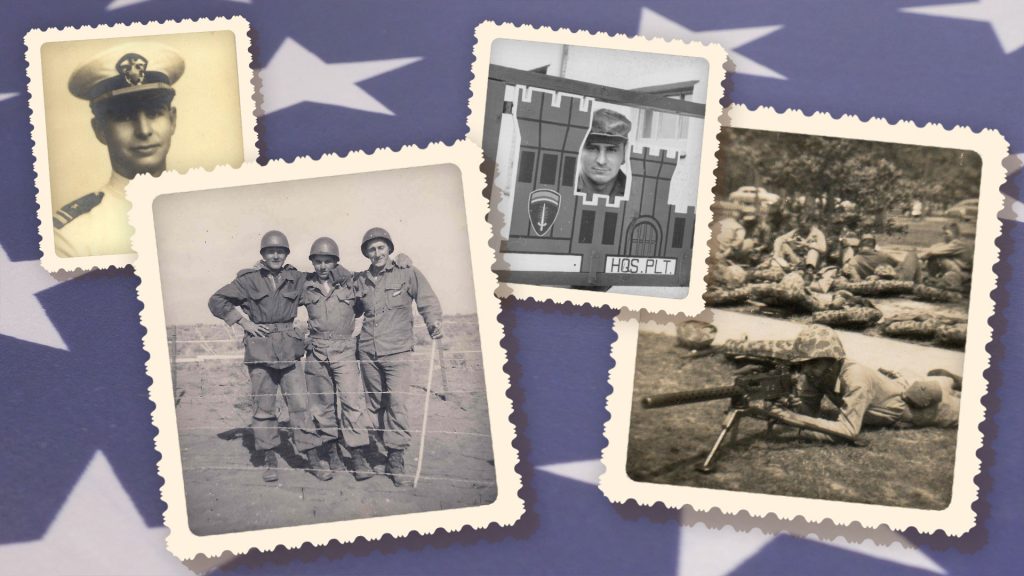

Service // In the Military

Ronald Paul Schexnydre Soldiers Boze Crochet Marine Corps training, early 1950s Clelie Hebert US Army nurse Boze Crochet One of the wild horses Boze caught while doing maneuvers with the Marines on an island near Puerto Rico. Melvin Daigle Melvin Daigle in France Landry Henry LaBarre Like all communities, members of the Grand Bayou community answered the call to serve in the U.S. MILITARY. From the world wars and beyond, the people of Grand Bayou and their descendants have served in the armed forces. World War II army air corps Earl P. Rousseau Son of Adele Dupré and Marcellin Rousseau, Earl Pierre Rousseau was a master sergeant in the US Army Air Corps during World War II. He was the top turret gunner in a B25 Mitchell and stationed in the Philippines for most of his service during the war. While he was away, he’d write to his mother, signing his letters with love, B-25 Mitchell was a medium bomber that was used by many Allied air forces in every theater of World War II. army Harold “Picou” Rousseau Another son of Adele Dupré and Marcellin Rousseau, Harold “Picou” Rousseau served as a corporal in the Army. He served in the 363rd Army Engineers in Iran during World War II. Harold also wrote letters to his mother, like the one pictured, signing it “lots of love to you,”

Growing Up // Childhood

JAY CROCHET with his billy goat and cart. STEVE ROUSSEAU LAWRENCE DUPRE Mamere’s brother with his children Wilamenia and Pat. WAYNE AUCOIN CAMILLE REAVIS AND BETTY BRELAND By Devin Griffin, Staff Writer Of all the things that went into living in Grand Bayou, the children that were lucky enough to grow up there knew what made it so special. In the close-knit community, kids of all ages grew up with adventures like crawfishing, swimming, climbing trees and, most importantly, growing up with family and room to explore. “Growing up in Grand Bayou was very different than even growing up five miles up the road in Paincourtville and so very different from the big city of Napoleonville,” says Loretta Rousseau Lirette, who grew up in Grand Bayou. “During the summer in Grand Bayou, we swam in the bayou, took afternoon boat rides in the bayou, made up so many games, read books, and were very often ‘bored.’ But we did have FUN, FUN, FUN.” In times of high water, she and her siblings would sit on the front porch and try to catch crawfish right outside their house.Clarence “Bud” Rousseau says he also spent his childhood crawfishing. “As a kid, we ate crawfish, but we also made money crawfishing.” Rousseau says they used to sell crawfish for 6 cents a pound. Behind his house, there were crawfish everywhere for Rousseau and his cousin to catch. “We would go and as fast as I could catch them, he would haul the sacks to the front of the street,” Rousseau says. “We would sell as much as we could sell in a day, six, seven sacks for like $3 a sack.” Greg Leblanc, another Grand Bayou native, says he would go fishing with his parents and help run the trawl lines during the day, and at night he would run around the porch knocking down lightning bugs. “And we would all swim in the bayou all the time,” Leblanc says. June Dupre Bouchereau, who grew up in Grand Bayou, says, “The adults never wanted us to go in the bayou by ourselves. There were no problems with alligators, but there were snakes. Whenever someone saw a snake they would just yell snake and we would all kick our legs, then it swam away,” But still, Bouchereau says the children spent a lot of their time swimming in the bayou, swinging from ropes hanging off tree branches tied in big knots, standing on tire tubes or tractor tubes and playing in paddle boats. “No matter the age, whether a few years older or a few years younger would all go to the big oak tree in someone’s backyard.” Bouchereau says.“I can remember being so little that I couldn’t wait till I could get this branch that stuck out enough to swing off the rope into the bayou. It was just so much fun.” While the outdoors was the landscape of childhood, the close-knit community was the heart. “There was a lady, everyone called her Aunt Lou, but she wasn’t everybody’s aunt,” says Nell Aucoin Naquin, who also grew up in Grand Bayou. “She was someone related to all of us like third, fourth, firth cousin whatever, but we all called her Aunt Lou.” Aunt Lou was really Lousie Dupré, Howard Dupré’s sister, says Jessica Rousseau Baye, Grand Bayou native. Lousie Dupré was a widow at a young age with four children and a waitress her entire life to provide for her family. Baye says when the tugboat operators would pass by down the bayou, Dupré made them draw out a pocket in the bayou side to make miniature levees, leaving a bench for the parents to watch their children swim in the bayou. “And we all learned how to swim in Aunt Lou’s pocket,” Leblanc says. Dupré taught each child in Grand Bayou how to swim, and when they could by themselves, she gave them a coloring book and colors. “I don’t know how she did it because she was so poor. That same lady gave everybody in Grand Bayou a big peppermint stick for Christmas,” Baye says. “She was such a free spirit and she loved to sing. We were all at Aunt Lou’s all the time.” Naquin says Dupré always managed something fun for all the neighborhood kids to do. Despite the grown-ups raising an eyebrow here or there, the kids absolutely loved her. “When things got boring, we could go to Aunt Lou’s and find something to do. She would have something for us to play with,” Naquin says. “There was always excitement there.” in her own words ICY ROUSSEAU LEBLANC Previous Next Denis, Kelly and Scott Naquin Carole Landry Bullock and Betty Crochet Breland Cousins Rickie Voisin David Hymel and Susan Hutchinson JAY CROCHET Loretta Rousseau Lirette Cousins Go-cart Dwight Breland and Joel Dugas Ginger Guillot Roussel Buddy LeBlanc Carole Landry Bullock and Camille Reavis Wanda Rousseau, Joy Rousseau, Michael Keith Whalen and Susan Whalen Farley Lynn Crochet Aguillard and Betty Crochet Breland

Memories // Telling Stories

https://gardevoirci.nicholls.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/gb_stories.mp4 By Chakyra Butler, Staff Writer The people of Grand Bayou say they will always have special memories of the place they once called home, some of these memories being unique to bayou life. Grand Bayou native Nell Aucoin Naquin says one of her greatest memories was when resident Ramona Talbot was bitten by a snake. Naquin was a sophomore in high school, and they would play croquet together on Talbot’s lawn. “She would normally always beat me,” Naquin says, “But for once I was ahead of her, I was beating her, and all of a sudden I heard her scream.” Naquin says she remembers watching on TV people that got bitten by snakes had to get their skin cut with a knife, with someone having to suck out the blood in order to get rid of the poison. “I was so afraid I was gonna have to do that,” Naquin says. She says Talbot’s mother was not home at the time, so they both walked to Naquin’s house and brought her to the doctor, who gave Talbot a tetanus shot and said the snake that bit her was not poisonous. “That scared the bejeebies out of me,” Naquin says. Although Naquin says that experience may not be her best memory—that would be having fun in the bayou with the kids—it is a memory that is everlasting. David Schexnaydre visited Grand Bayou often, and says he remembers a story his mother told him. Schexnaydre says his uncle Picou went with a man to Morgan City on a type of raft to pick up supplies for the stores in Grand Bayou and Bayou Corne. When they got back to the landing in Grand Bayou, revenuers, government officials who enforce laws prohibiting the illegal distillation or bootlegging of alcohol, were waiting for them. “It wasn’t groceries they went get, it was moonshine liquor,” Schexnaydre says. Schexnaydre says he remembers his mother telling him the revenuers started shooting, and everyone, including his uncle Picou, tried jumping into the bayou. “Uncle Picou jumped in the bayou, and he had high top boots on, and I think mama said they had steel toes in the boots,” Schexnaydre says. He says his uncle swam to the other side of the bayou and hid in the lilies all day until the next night. “I believe that’s the way the story went,” Schexnaydre says. Another story Schexnaydre says he remembers being told was when he and his two eldest brothers, Ronald and Barry—the latter nicknamed Tede—were playing on his uncle Dodd’s front yard. “Tede tried to climb up on Uncle Dodd’s big live oak tree not knowing that there was a mink trap in the fork of the tree,” Schexnaydre says. Schexnaydre says when Tede climbed up, the trap caught his hand and he could not move. “My older brother Ronald ran into the house and said, ‘Mama. Mama. Come quick, Mama. Tede’s in a coon trap, in a rat trap, in a possum trap, in some kind of trap come quick, Mama,’” Schexnaydre says. Since then, Schexnaydre says when they visited their uncle’s house, the first thing his uncle would do was hoot and say, “Tede’s in a coon trap.” grand bayou STORYTELLERS UNCLE PICOU NELL AUCOIN NAQUIN DAVID SCHEXNAYDRE

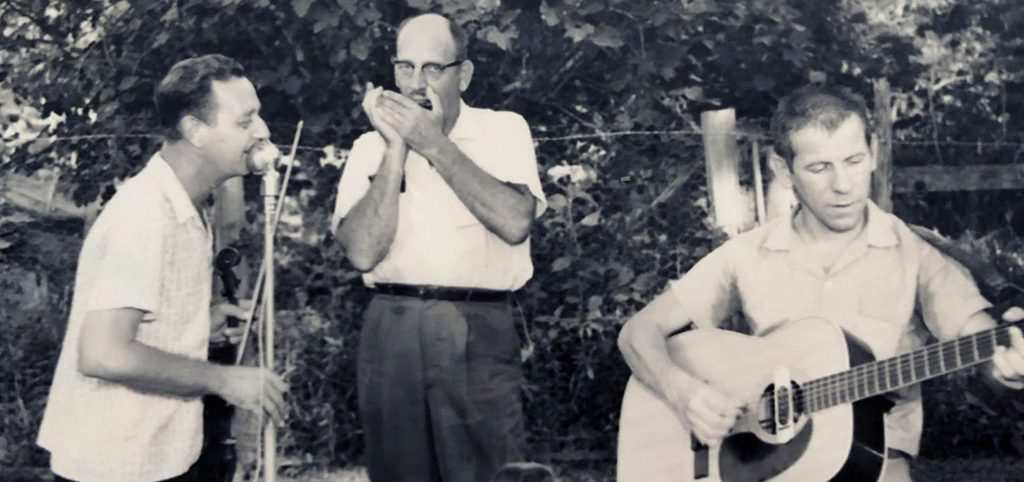

Passin’ A Good Time // Entertainment

By Shaun Breaux, Features Editor When the people of Grand Bayou were not playing or swimming in the bayou, they would often have big neighborhood visits. While there wasn’t anything fancy to do in Grand Bayou, residents say they would find their own entertainment. “Whether it was playing cards or other games or just watching other people do the stuff, we always laissez les bon temps rouler (let the good times roll),” says Grant Gautreaux, a Grand Bayou native. At these popular house parties, people played games like Pedro, a sneaky card game, to Bourré, a trump or trick talking game. “Nothing more friendlier than a pedro winner,” says Barry Schexnaydre, who visited family in Grand Bayou frequently. While the rules varied from parish to parish, finding a South Louisiana native that doesn’t know how to play these games is the exception, says Schexnaydre. Before house parties became the main source of entertainment in Grand Bayou, a fais do do was the place to be. The name fais do do is referred to as a party where traditional Cajun dance is performed. The phrase literally means “to make sleep” and derives from the children going to bed before the party could begin. Street dances associated with festivals are also sometimes called fais-dodo in Cajun culture. Jessica Rousseau Baye, Grand Bayou native, says that when they went out, they would go to Pierre Part or Donaldsonville. “That was, you know, the places where they had bands and music,” Baye says. “We weren’t sheltered from that part, at that age.” Although former Grand Bayou residents say they now find it hard to recall memories of when dance halls in Grand Bayou did exist. The Bon Chance Club was introduced in the 1930s. Bon chance means “good luck” or “good courage,” making The Bon Chance Dance Club the center of entertainment in Grand Bayou at the time. “That would have been way before my time, but yeah there was a little dance hall and they would have dances. My daddy, Howard Dupré Jr, used to play sometimes. He would have a guitar and a harmonica around his neck, play them both at the same time and then sing. I don’t know how he did it all at one time,” says Joey Dupré, Grand Bayou native. Dance halls in Grand Bayou and throughout southern Louisiana flourished well after the early years. A flyer from the Assumption Pioneer in 1976 says, “Deep in your heart, don’t you prefer dancing at the old Gear Room (150 years of dancing pleasure). Music by Herman Couple and his boys every Saturday 9 p.m. to 1 p.m. and Sunday 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. Free dance every Sunday except holidays and free supper at the Hulla Hoop every Tuesday.” The bottom of the flyer read, “Hwy 69, Grand Bayou.” GAMES DANCING CRAWFISH BOIL BIRTHDAY PARTY Grandfather Howard’s Birthday Party CARD GAMES HAZEL ROUSSEAU AUCOIN AND KELLY NAQUIN ANDERSON Playing Scrabble A GRAND BAYOU PARTY

Talkin’ // Speech in Grand Bayou

Every community has its own way of speaking, from phrases to mannerisms to nicknames. But throw in some French Acadians in a protected rural environment, and the culture is ripe for speech that is hard for outsiders to understand!

The Center of Faith // St. Elizabeth

By Chakyra Butler, Staff Writer In Paincourtville, about five miles away from Grand Bayou, stands a brick, Gothic-style Catholic church with twin towers. St. Elizabeth Church has been the religious center of the area, including Grand Bayou, for more than 100 years. “It is still just so special,” says Jessica Rousseau Baye, a Grand Bayou native. “It’s a huge, beautiful church in a very very small community. There are so many of those in Louisiana, but ours is special.” For some residents, the church’s physical appearance makes it stand out. “It is gorgeous,” says Jerry Rousseau, 81, a Grand Bayou native who has been attending St. Elizabeth Church since he was a baby and was even baptized there. “It’s a Gothic-style church. All paintings on the ceilings and all that.” He says the church has not changed much since he was a child, except for the altar being changed. Almost everything else, like the seats, are the same and, he says with a smile, the seats are still uncomfortable. At one time, churchgoers paid for their own pews. Families often paid 25 cents to “own” a pew, designating that spot in the church as their assigned seats. Rousseau says he remembers his family owning a pew on the left side of the church. Now, Rousseau says visitors sit wherever they want. While the physical structure is memorable, parishioners say it’s the life lessons that mean the most. “When I go in that church, I just see all my family there,” says Betty Crochet Breland, who was born and raised in Grand Bayou. “I see all the Grand Bayou people.” Breland and Baye’s shared grandmother, Adele Rousseau, was the bride in the first officiated marriage held in St. Elizabeth. Breland says St. Elizabeth was the center of the surrounding towns. Grand Bayou, Bayou Corne, and the church brings back memories of communities coming together to worship. “It’s always going to be a part of our lives,” Baye says. “It’s never gonna go away.” People who have moved away from the area still travel back to St. Elizabeth to have Mass and bury family members. Baye says she now goes to St. John the Evangelist in Thibodaux, but she and her family still go to St. Elizabeth for special events. And as Baye told the last of her grandchildren who attended St. Elizabeth School: “No matter where you go, you are never gonna find another school and church like this in your entire life. You will always have this memory, and it’s beautiful.” Charles Hebert’s first communion at St. Elizabeth. The painted ceiling at St. Elizabeth. Janet Daigle and Perry Blanchard’s wedding at St. Elizabeth. Addie Rousseau and Mabel Hebert’s wedding certificate from their wedding at St. Elizabeth. Hazel and Ellen Aucoin at Ellen’s confirmation. Olga Rousseau’s baptismal record from her baptism at St. Elizabeth. CONFIRMATION First cousins making their confirmation together. From left: Dale (Hazel), Jessica (Picou), Clyde R (Alma), Katherine (Nice), Uggy (Roy), Cookie (Alma) The St. Elizabeth altar. Second Communion

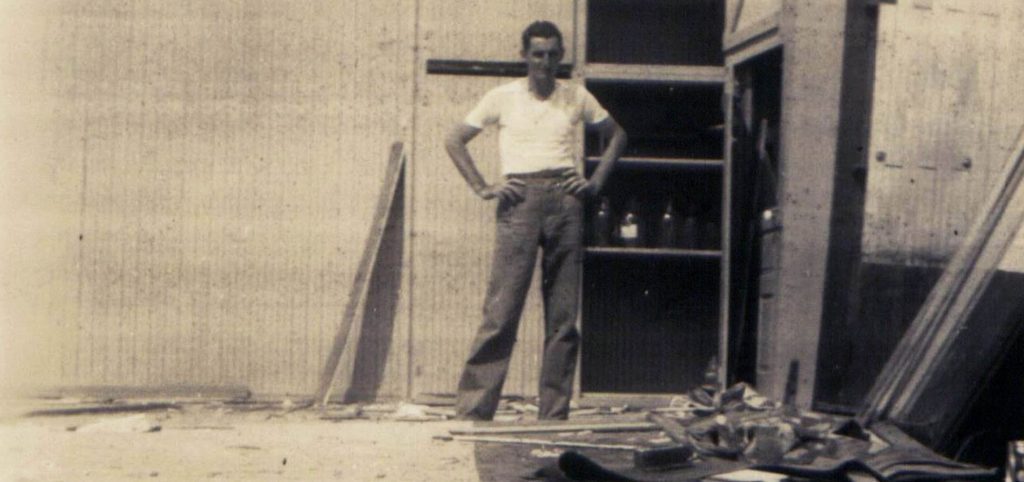

Work // Making a Living

By Emilee Theriot, Staff Writer Grand Bayou was once the home to a thriving business community including a saw mill, a cotton gin, a broom factory, a moss gin, a country store, a dance hall and a barber shop, according to the Assumption Pioneer and documents written by former resident Hazel Aucoin. Growing up, Aucoin says she remembers the men doing mostly swamp work. They cut cypress and floated it down the bayou. They dredged canals, so the men could get to work cutting the cypress trees. They used cypress to make crossties, roofing shingles and cistern staves. Some men worked at a dry dock where boats and barges were built and repaired, while other men did carpentry, picked moss for the moss gin or worked for the sugar factory. People hunted and fished, made gardens and milked their own cows. “In those days moss was in everything, car seats, mattresses, etc.” says Jerry Rousseau, who grew up in Grand Bayou. “The moss business dried up because something better was developed.” Rousseau’s grandfather ran the moss gin that operated in Grand Bayou, where Rousseau said he remembers playing in the early 1940s, once it was abandoned. The first bridge over Grand Bayou was named La pon Ford, meaning Ford’s Bridge, after the man who built it. Aucoin says there were no gravel or paved roads, only dirt roads. Businesses and the community used waterways for transportation. In 1953, Aucoin’s husband died at a young age, leaving her with four children to raise. One of Hazel’s children, Nell Naquin said to support her family, her mother sewed and cut men’s hair. She also made wedding dresses and prom dresses. “Every Friday men would show up from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m, to get their hair cut in the family kitchen,” Naquin says. Dirt roads turned to gravel roads and ultimately paved roads. Grand Bayou’s businesses and workforce changed from cypress cutting and moss picking to retail and other industry. By the 1940s and 1950s, Grand Bayou consisted of a grocery store, gas station, Priscilla’s restaurant, wholesale seafood business and trucking companies, says June Dupre Bouchereau, a former resident. Dupre’s family owned and operated the Howard J. Dupre Jr. Grocery Store and gas station. The store carried general merchandise like fresh fruit, beans, kerosene, canned goods, meats, soft drinks, beer, bread, brooms and more. Residents also worked in businesses outside of Grand Bayou. Bouchereau and some of her friends commuted to Donaldsonville to work at B. Lemann & Bros. Department Store. Some of the Grand Bayou men worked offshore while others worked at chemical plants along the Mississippi River. Sugar cane farming was a common business in and around Grand Bayou. Bouchereau says her Dupré family store—next to the family home—had a porch in front where men would gather. “It had double front doors with a cash register to the right of where you walked in. There were great big counters to the left and big shelves in the middle, in the back were more shelves and a back door with wooden steps,” Bouchereau says. In 1954, her father, with help from the community, built a larger store on the other side of their house. “At Grand Bayou, everybody kind of helped each other build boats and houses,” Bouchereau says. Tracy Scioneaux, who lived in Grand Bayou from the 1970s to the early 2000s, says her family also owned businesses. Her grandparents, Youman “Buck” and Maggie Albarado, owned and operated the Buck’s Inn restaurant, a popular eatery that closed in the early 1970s. Her father, Edward Scioneaux, operated a number of businesses to support his family of nine. The family had a trucking company, the Three Way Mobile gas station, and also grew and harvested sugar cane. All seven children worked in one or more of the family businesses. “My parents taught us to work at a young age,” Scioneaux says. She says her fondest memory growing up was going to the fields at the end of grinding and celebrating her dad’s last day of harvesting with her family. Edward Scioneaux sold his sugar cane to a local sugar mill. Jason Blanchard’s grandfather, Morris Daigle, worked at the Lula Sugarcane Factory in Belle Rose, La. for 47 years. “He ran the repair, maintenance and construction at the mill,” Blanchard says. He says his grandpa was an engineer and created a hydraulic lift to quickly connect and disconnect trucks from the cane trailers among other inventions. Grand Bayou has seen a lot of changes over the last one hundred years. Gone are the residents and all the family businesses. The once thriving business community of Grand Bayou consists of one local business, a convenience store on the corner of Louisiana Highway 70 and Highway 69. The sugar cane fields and cotton fields are now the site of the Texas Brine Plant and the Dow Chemical Brine Production and underground storage facility. Addie Rousseau drove crew boats to the oil rigs in Grand Bayou. Howard Dupré Jr. in front of his general store. Scioneaux Trucking Company Morris Daigle, an engineer, with one of his creations at a sugar mill. The Buck Inn

Food // A Family Centerpiece

By Jade Gallaher, Staff Writer Food in Grand Bayou was not only the center of family gatherings but was also a celebration of the land where they lived. “I can remember for years and years, my mom and her sisters would get together every year and would get several sacks of crawfish and make crawfish bisque at one of their houses,” says David Schexnaydre, who visited Grand Bayou often. One of his favorites, crawfish bisque is peeled crawfish tails mixed with onions, garlic, breadcrumbs and various other spices that are then stuffed into the cleaned heads of the crawfish and fried. Brown gravy is poured over the top of them before serving, Schexnayrdre says. Grant Gautreaux, one of the last people born in Grand Bayou whose mother’s family were in the commercial fishing industry, says seafood and crawfish were a staple. “We ate a lot of crawfish in all types of forms, lots of stews, a lot of boiled crawfish, fried crawfish tails and fried fish,” Gautreaux says. “If one of my uncles would go catch a sack or two sacks of crawfish, everyone would sit around to peel them and take home their share of the crawfish.” The people of Grand Bayou may have all lived within the same community, but the meals on every table were different. While most recipes were different variations of the same ingredients, other dishes included corn soup, potato stew and crepes.A lot of the families’ food came from the land they lived on. “You had a lot of native fruit. There were persimmon trees, there were muscadine vines, there were maypops and there were honeysuckles,” says Greg Leblanc, a Grand Bayou native. These fruit trees are indigenous to South Louisiana and have disappeared from many places known to the people of Grand Bayou because of land damage.A lot of Grand Bayou residents grew up watching their parents bring produce from their farms to the table. “My father was a farmer and grew corn. So, he would say, ‘Momma, wanna make corn soup today? I’ll go get a mess of corn, and then we’d make corn soup,” says Jessica Rousseau Baye, who grew up in Grand Bayou. Eating from the earth the majority of the time was not the only thing most of these families had in common, but also that they had meals together. “We always ate together,” Baye says. “Other than breakfast, because we were going to school and catching the bus. Daddy was in the field probably earlier than us. But, on weekends, lunch and supper every night we ate together at a table, and I think that is not done very much except on special occasions.” a few grand bayou Recipes

High Water // A Seasonal Reality

Education // Bayou Way of Learning

By Shaun Breaux, Features Editor Grand Bayou may not have been the biggest or most developed area, but for the people born and raised in this bayouside community, they made it work not only out of necessity, but because they enjoyed their way of life. “Being five miles away from everything, like the grocery store, church and school, we were kind of isolated in our own little beautiful community,” says Jessica Rousseau Baye, Grand Bayou native. “We had a wonderful childhood; we didn’t know that there was anything different to us.” Nell Aucoin Naquin, Grand Bayou native, says that although there may not have been many industrial places in the community, to them, there was a lot around. “I mean there was the great outdoors. The world was ours,” Naquin says. “We got to swim in the bayou everyday, we got to walk in the woods and look at all the animals and the creatures. We got to fish and supply our food from the animals, the land and the bayou. We grew our own food, so there was a lot to do and see.” Grand Bayou’s lone schoolhouse was abandoned in the 1930s. Once roads improved, children were able to travel or be picked up by bus to attend school five miles down the road in the nearby town of Paincourtville. Naquin says that old schoolhouse was where she was born and raised until she was about four years old. “My mom and my dad turned that house into our home. Eventually my momma bought that property and the building, tore the schoolhouse down and used the lumber from the schoolhouse to rebuild the house that I pretty much grew up in,” Naquin says. The children of Grand Bayou during Naquin’s childhood in the late 1950s attended St. Elizabeth’s School in Paincourtville about five miles away. They went to Catholic school until 7th grade and were taught by nuns. Baye says the Catholic foundation was essential for their education. Tuition for Baye and her siblings was $3 per person per month around this same time. Baye says for the four of them, that $12 was hard to come by. She says she remembered her parents struggling during some months, as Baye’s father worked as a small farmer on leased land. “Still, We always had a car, and we always ate well. I never felt poor, but when I became an adult, I knew we had been poor,” Baye says. From there, they attended 8th grade six miles away in Belle Rose and Assumption High in Napoleonville for high school 11 miles away. After high school, Naquin rode the public bus from Grand Bayou to Nicholls State University every day until graduation. Nicholls is located in Thibodaux, around 30 miles from Grand Bayou. Naquin says she knew a lot of Grand Bayou residents, herself included, who would not have been able to get a college degree if the parish would not have sent school busses to pick them up and bring them to Nicholls. She says she rode the school bus for her entire educational career and was thankful for the bus that picked them up every day. The generation before them had more than just a bus ride to endure. Baye says her mother went to school in Belle Rose, but it only went up to 11th grade. After graduation, her mother started teaching in Pierre Part, which she had to get to by boat. “My mother taught second grade with an 11th grade education. She was a very smart lady,” Baye says. Baye’s father only had a fifth grade education, but he continued to teach himself. “During the war, he was always reading Time Magazine and Newsweek Magazine, so he was self-educated. I think that when you’re in the war and you travel to other parts of the world that’s education in itself,” Baye says. The former residents of Grand Bayou talked about their childhood much like other rural communities of the 1950s. Yet unlike those communities, they had the bayou to explore, gaining an entirely different type of education and set of skills. Grand Bayou’s one-room schoolhouse before it closed in the 1930s. Grand Bayou’s one-room school class picture. St. Elizabeth School in Paincourtville about five miles from Grand Bayou. Previous Next