The Great Storm Timeline

Isle Dernière’s THE GREAT STORM of 1856 Friday, August 8 2 Days Before High waves and higer than usual tides. Saturday, August 9 1 Day Before Marshes around the island were submerged, animals were unsettled and The Star had difficulty sailing down the Atchafalaya through Four League Bay into Caillou Bay. Sunday, August 10 Morning Storm Day The Star, having difficulty navigating, continued to the island to help those they could. Sunday, August 10 4 pm Storm Day The winds shifted and the waves battered the drowning island throughout the night. Monday, August 11 1 Day After Nothing was left on the island. Tuesday, August 12 2 Days After Last Island Hurricane dissipated over southwestern Mississippi Figured no one on mainland knew survivors were stranded Resort guest, John Davis set out on a sailboat to the mainland Davis arrived the Brashear City Hotel before dawn reporting that Last Island had been swept away by a storm Help dispatched in all directions to announce calamity & crippled conditions of survivors Wednesday, August 13 3 Days After Help arrived from Brashear City (Morgan City) Wednesday, August 20 10 Days After Pirates looted valuables. click to the right for a full, detailed timeline of the Great Storm of 1856

The Great Storm

By Michael Gros Brand & Visual Editor The four Muggah brothers were riding high at the opening of the 1856 summer season on Isle Dernière. In February of that year, a deal was struck with investors from the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans to improve the hotel. Construction was set to begin at the end of the season and the goal was to construct the largest hotel in North America. The new and improved hotel would be capable of hosting 1,250 guests, have a new 320-foot by 60-foot dining room and 1,250 feet of double-decker galleries overlooking the Gulf of Mexico and the surrounding bay. By the beginning of August, with just one month to go before the season expired and people went back to their lives on the mainland, the island’s population grew to 400 residents, all vying to soak up the last remaining days of summer. Among the 200 guests staying at the hotel were Mrs. Laura Sims and her husband. Mrs. Sims had overcome a serious illness which then caused her to be diagnosed with dropsical. “The physicians who attended me recommended surf bathing.” she said in an 1895 letter to the Shreveport Times, “They thought Last Island the best place for me, as it had notoriety as a health resort, we were nothing loth to go.” On Friday, the 8th of August, guests began to notice the breeze shift and start coming from the North East. As people were walking back to their homes, they noticed an overabundance of seabirds taking shelter in the islands dense forest behind the summer cottages. Also, that night, the frogs and cicadas had fallen silent leaving the island eerily silent. One visitor, Captain Jimmy of the yacht Atlantic, noticed the higher than usual tide and brought his concerns to Thomas H. Ellis, a captain and son of a wealthy Terrebonne Parish sugar farmer. With his 40 years of experience as a sailor, he feared Isle Dernière would be in severe danger within 48 hours. Saturday morning was like any other Saturday. Fishing and hunting, surf bathing and riding were the norms. The steamer Star, helmed by Captain Smith made a scheduled run to Morgan’s Railroad, modern-day Morgan City, and would make a quick turnaround for the second round of guests. By evening, the much-anticipated ball at the Muggah hotel was underway. While a storm was raging outside, guests danced and drank wine to ease their concerns about the storm. Captain Dave Muggah, the youngest of the brothers Muggah, assured guests. That they were experiencing the worst of the storm and assured his guests that wine and music would ease their minds. “If the storm doesn’t blow over by morning,” he said to his anxious guests, “no fear, the steamer Star will soon arrive to take you all back to the mainland.” Little did Captain Muggah know, the Star had been blown off course. Colonel W.W. Pugh states in his memoirs that “all our cares vanished as we danced. Little were thinking of the sad changes which a few hours would bring about. I recall with sadness the skill and taste of the old German; whose violin furnished the exquisite music, which charmed so many. Our party broke up after midnight, and the exhausted crowd sought their couches fortunately ignorant to the fate which awaited in a few short hours.” On Sunday morning, the. Star docked safely back on the mainland, however, Captain Smith insisted that he return to Isle Dernière to save as many lives as he could. Riding with him was Thomas Ellis. By early afternoon, the brunt of the hurricane was upon the island. Walls of storm surge engulfed the island from the Gulf and Calliou Bay. By 2 o’clock, the first floor of all structures were engulfed with water and by 3 o’clock, the wind gusts began to rip apart the cottages on the island. Within seconds, a tidal wave smashed the maritime forest on the west end of the island. As the hotel took on water, guests scrambled to the second floor to escape the storm surge. As they clung together, the second floor began to wobble and buckle from the wind. A welcomed sight was the smokestacks and lanterns of the Star. Island resident Michael Schlatre walked through blinding rain to the hotel to watch the steamer dock safely. Shortly after, his slave found him to report that his home was gone. Thomas Eilis stood on the bow of the Star to survey the island. To his horror, no structure was standing. Captain Smith and Ellis began to lift survivors into the hull, who had formed a human chain to pass people safely to the ship. According to guest Dr. Thomas Kramer, the last person in the chain was a slave girl. She was lost as the hotel gave way. Around 4, the winds died down. Mrs. Sims said “By this time I was almost dead. Looking up we saw not more than 100 yards from us the hull of the Star, a stranded wreck, chimney gone, cabin cutaway, and one of the large side wheels lying upon the deck.” If it weren’t for the brave Capt. Smith, who saw her and her husband and roped them to safety, they would have perished. Just as the winds calmed, they reared their ugliness, this time changing direction as the eye moved over the island. For the rest of the night, wind, rain and waves battered the drowning island. The following morning, all was quiet. The Star had taken the place of the hotel. Except for the remaining people on the steamer, only one cow, one horse, and a few sheep survived. By Tuesday, a resort guest named John Davis made his way to the Brashear City Hotel to alert people that Isle Dernière had been washed away. As South Louisiana awoke to the news of the island, many other communities faced the same disaster. The village of Abbeville was flattened and sugar cane fields

An Island Timeline

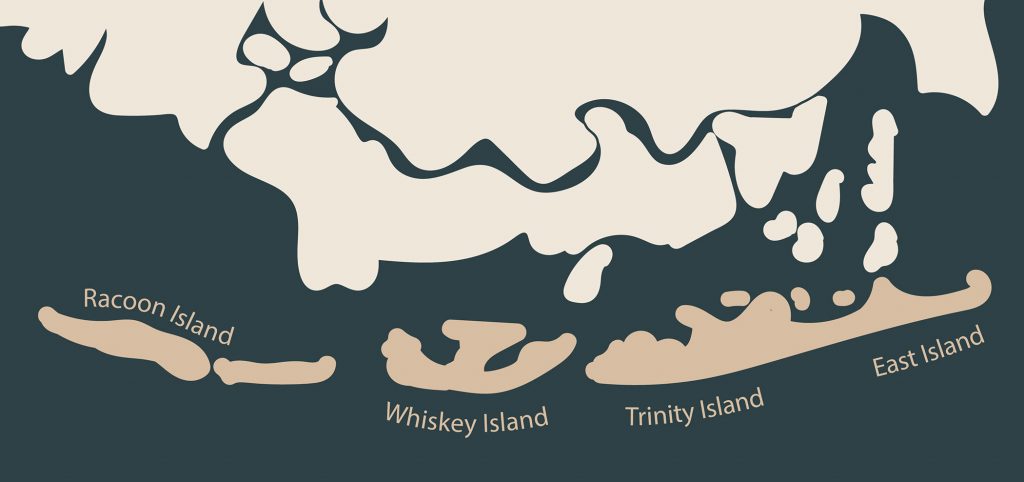

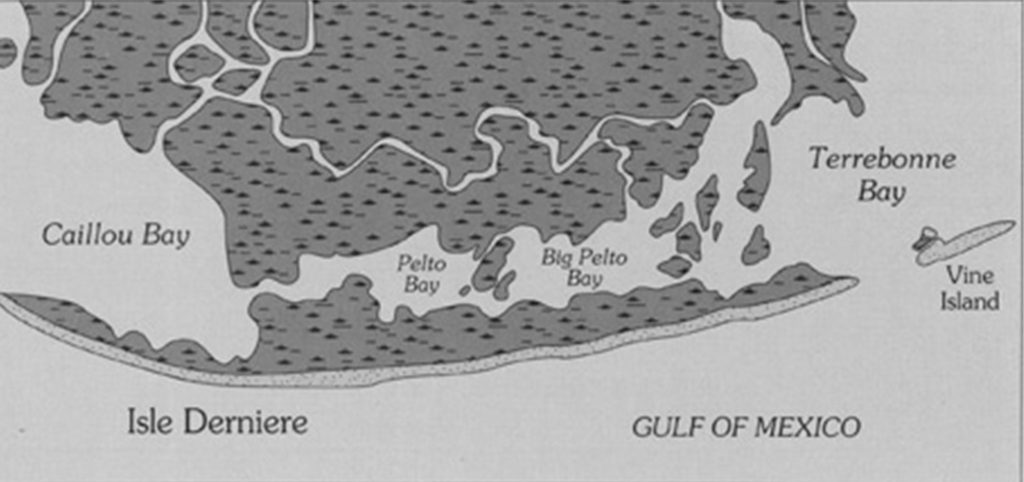

a timeline Isle Dernière 1800 Untamed Land A raw, natural island oasis 1830s Rustic Getaway Small fishing huts existed on the island. 1840s Land Purchased Developers began to purchase land from the US government. 1848 Resort Established The four Muggah brothers along with financers from St. Mary Parish developed the Ocean House Hotel. 1856 Bigger Plans Plans were made by the four Muggah Brothers, along with the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans, to begin construction for a bigger, more elaborate hotel dubbed the Tradewinds Hotel after the summer season in 1856. August 10, 1856 The Great Storm A category 4 hurricane destroyed the entire island, breaking it into four islands — Racoon, Whiskey, Trinity and East. Today Protected Wildlife Area Most of the islands is protected for sea birds and other wildlife.

The Island Today

By Kia Singleton Photo Editor After the 1856 hurricane that destroyed the resort of Isle Derniere, all that was left on the island were seabirds. Over time, the remainder of the island was separated into five smaller islands known as the Isle Dernieres Barrier Islands. These barrier islands are Wine Island, East Island, Whiskey Island, Raccoon Island, and Trinity Island. Now owned by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, the islands are mostly protected space for waterbird nesting. But a portion of Trinity Island, the island farthest east of the Isles Dernieres chain, is accessible for public use. People can picnic, fish, camp overnight, and bird watch in permitted areas, according to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. While the activities on the island are restricted, the waters surrounding the barrier island refuge are a popular recreational fishing destination. Mr. Lance Schouest, also known as Captain Coon, is a Tour and Fishing Guide at the Tradewinds of Cocodrie, which is a marina and lodge northeast of the Isle Dernieres Barrier Island Refuge. During a phone interview, Schouest said, “It’s a pleasure to see people catching fish and seeing the enjoyment on their faces, and that makes getting up at 4:30 in the morning to work in the heat worth it.” He also explained that he takes all his customers to areas where the fish are most active. He said, “The fish are always biting.” Trinity Island has more human activity than any of the other barrier islands. On Trinity Island, people can travel by foot or by bicycle. The use of ATVs or other vehicles with engines or electric motors are not allowed on the island. Firearms, fireworks, and explosives in the public area are not allowed. To utilize the public area, a visitor must have a portable waste disposal container for human waste. This means there are no restrooms on the island. No one can disturb, injure, or collect plants and animals. Fishing from boats is allowed as well as wade fishing in surf areas. Boat traffic is allowed in open waters, like gulfs or bays, and within the California Canal. However, no boat traffic is allowed in any other man-made or natural waterways that extend into the inside of the island. Boat traffic is also not allowed in land-locked open waters or wetlands. Captain Paul Titus created a GPS tool with coordinates for fishing spots near these barrier islands. These spots are called waypoints. According to an article from LouisianaSportsman.com, “Captain Paul’s Fishing Edge of GPS Waypoints of the Cocodrie-Dulac area is located from Point au Fer Island, Four League Bay to the east of Cocodrie from the Gulf of Mexico by Isle Dernieres to Lake De Cade by Bayou DuLarge.” This is the southern part of Terrebonne Parish. A location between Whiskey and Raccoon Islands is known for being a great fishing spot; the coordinates are 29 degrees 02.9948’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 52.7825’ W. Longitude. There is also a U.S. Geological Survey Benchmark for “Coon Point”. At one time, this was western part of Raccoon Island. The coordinates for Coon Point are 29 degrees 03.5490’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 57.6655 W. Longitude. Between Trinity and East Islands is a waypoint with deeper waters than any other locations in the area. The coordinates are 29 degrees 03.7278’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 41.5423’ W. Longitude. A location known as “Horseshoe Reef” is said to be a popular summer destination. It is in the northwest part of Trinity Island, which is east of Whiskey Pass. The mouth of the cove at Horseshoe Reef coordinates are about 29 degrees 03.395’ N. Latitude and 90 degrees 44.521’ W. Longitude. Trinity and Raccoons Islands are more accessible than Whiskey, East, and Wine Islands because of the bird habitats, the designated public areas, and the abundance of fish. Most of these areas are occupied simply by fishermen. If someone would want to spend time on the barrier islands, filing the correct paperwork with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries is imperative. a little Island Fun Check out the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries for more information on access to Isles Dernières. More Information Island Activities birding picnicking fishing camping PODCAST Dr. Quenton Fontenot, professor and head of Biological Sciences at Nicholls State University, discusses the barrier islands today. Garde Voir Ci · Season 3, Episode 4 – Isle Dernière Today with Dr. Quenton Fontenot

Island’s Long-Battled Ownership

By Payton Suire Managing Editor Eight years before Last Island was destroyed by a hurricane, the Voisin family began a land dispute that wouldn’t end for almost two centuries. In 1848, people began to question who owned Last Island when the State Land Office began selling tracts of land on Isle Derniere. Jean Joseph, J.J., Voisin, son of an eighteenth century French immigrant, confronted the purchasers, Thomas Maskell and James Wafford insisting that his family owned the island, which had been in the family for 70 years, by a 1788 Spanish land grant. In the Public Land Claims, it says “a Juan Voisin, una pequeña ysla, vulgarmente llamada L’Isle Longue . . .” (“to Jean Voisin, a small island, commonly called L’Isle Longue . . .”). The claim describes the location of Isle Longue as “situated in the Lake of Barrataria, adjoining (or contiguous to) on one side Last Island, and on the other, fronting the island called Wine Island.” On July 1, 1833, J.J. Voisin submitted documentation for claims on two tracts of land: Pointe-à-la-Hache and Isle Longue. A neighbor, Charles Carel, someone well-acquainted with the island, made an affidavit, “it has always been in his [Voisin’s] possession or in that of those who held it for him,” The 1788 order of survey and testimony supported Voisin’s two claims. In 1835, Voisin made another claim to the land when the U.S. Congress enacted legislation confirming the original grant, according to Public Land Claims Number 4533. In November of 1837, Gilmore F. Connely, a deputy surveyor, contracted with the State Land Office to survey portions of Terrebonne Parish, including “all the islands on the coast.” Four years passed before the surveys were certified, and two years later in 1844, the State Land Office added a second annotation to the west end plat. Last Island was for sale, according to the Last Island Survey Plats. The increased demand for land on the island corresponds to the “discovery” of the island’s sandy, white beaches. By 1846, steamboats and sailboats regularly took visitors to the island. Some began constructing cottages or summer homes along the beach. Last Island’s popularity spread, and on April 8, 1848, St. Mary Parish sugar planter, Thomas Maskell, purchased 160 acres for about $200, worth about $6,600 today, according to the Bethany Bultman Papers about Isle Derniere. On July 13, 1848, James Wafford purchased 53 acres west of Maskell. When confronted by Voisin, one purchaser, Alexander Pope Field, used a military warrant to claim his 100 acres and a Louisiana Surveyor, Gen. R. W. Boyd for a ruling. Boyd explained that in his office’s survey of Last Island, there was no survey or knowledge of Isle Longue. In the Public Land Claims, Voisin’s lawyer, F.C. Laville, questioned when he could expect to receive his patent but went months without reply. Boyd finally replied stating an island named Isle Longue “has not yet been surveyed.” This explanation failed to impress Laville who explained the name of Isle Longue had changed over time to L’Isle Derniere or Last Island, but the argument failed. The dispute intensified when Voisin moved his family to Last Island in 1849. In 1854, Wafford’s attorney filed suit in Houma to evict Voisin from his property and assess the damages from his actions. On November 28, 1854, Voisin’s attorneys filed a civil suit countering the claims of Wafford declaring Voisin to be the “true and lawful owner” of an island “wrongfully” called Last Island. They presented three documents: the 1788 Order of Survey, the Register’s recommendations, and the 1835 Act of Confirmation and asked for 3,000 dollars in damages, about 93,000 dollars today. As the chaos and contradictions ensued, the 1855 court calendar came to a close with each side eager for a winter break from court proceedings. The judge announced the case would resume in 1856 — the year the Last Island Hurricane hit. “Within weeks, the slow-moving trial would be upstaged by another slow-moving presence, a large counter-clockwise cloud formation stirring in the eastern Gulf ofMexico. A huge storm was inching slowly toward Louisiana’s central coast,” according to The National Hurricane Center (NHC) the Atlantic Hurricane Database Reanalysis Project. “After the storm, I think he just lost interest in it,” said Jeanette Voisin, a descendant ofJ.J., in an article by Houma Today, who is fighting for the land rights. “Everyone died out there. No one wanted to go back.” According to the book “Last Days of Last Island,” South Louisianians lost interest in the ownership of Last Island in the storm’s aftermath. The entire village was washed away in one afternoon leaving the trial to end gradually. In 1859, a judge postponed the case indefinitely due to the parish being invaded by the North as the Civil War ensued. After the Civil War, the dispute was reopened one final time, but most of the litigants and witnesses were dead, old, sick or weak. The judge placed the trial on a “dead docket” constituting neither a dismissal nor termination of the case in which it can be reinstated at any time. The file of documents, testimonials, and maps would remain untouched for generations. Flashforward to 1988, James Voisin was gathering information for the Voisin family tree when he found a spotted, faded brown pocket folder with a file titled “Jean Joseph Voisin versus James Wafford, et al.” He recalled a story his father, Everett Voisin, told him. During the ’50s and ’60s, Everett Voisin operated crew boats in the Atchafalaya River Basin when a coworker showed him an offshore drilling map with the name “Voisin” penciled along a small island situated in the middle of Isles Dernieres. Everett never pursued the information. Who Owned Last Island? Solving a Centuries-Old Louisiana Puzzle. Twenty-five years later, James Voisin shared the story with the rest of the family, which, after months of discussion, decided to engage an attorney. In late 1989, Lexington attorney Tim Hatton wrote to the Bureau of Land Management on behalf of the Voisins. “Jean

Fortunes Lost and Stolen

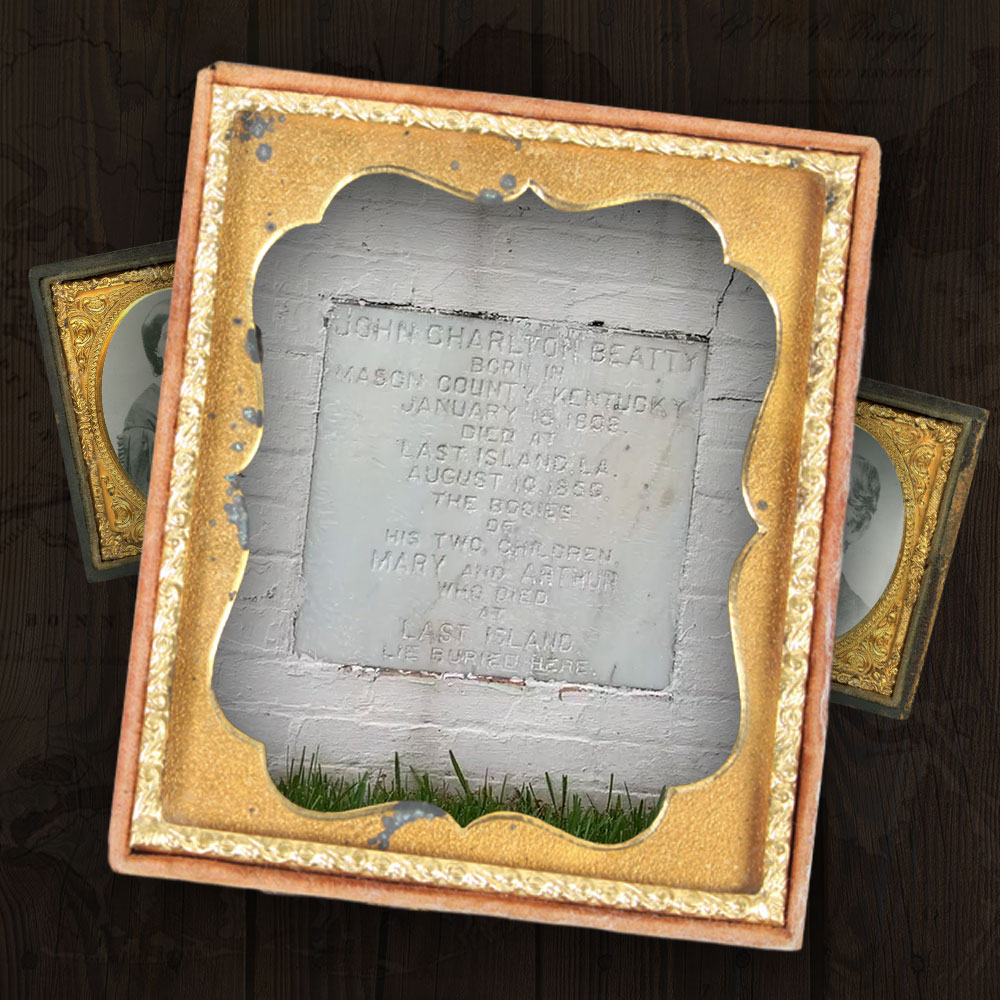

By Kia Singleton Photo Editor The Last Island Hurricane of 1856 is one of the worst storms to hit Louisiana with the impact destroying the whole island and causing over 200 deaths – the majority of the island’s population. Valuables remained scattered on the island, some still in the possession of the rich, powerful vacationers’ or their families’ corpses. Pirates looted anything leftover on the island. The Times-Picayune article in 1856 stated “During Mr. Richard’s absence from his store, a negro, belonging to the Hon. J.C. Beatty, went to purchase some goods, when the clerk observing that the fellow had in his possession a new watch and chain, felt his curiosity- and perhaps his suspicions – excited, and asked the n- to tell him the time.” It was very uncommon for someone like him to flash valuable items during this time. The man mentioned in the newspaper article was found and sent to jail where he confessed to having the watch and chain and that he possessed other valuables hidden away. The article did not mention how he originally got the items in his possession. These valuables were found on the people who had died on the island, according to the 1856 Times-Picayune article. He described where the jewelry was stashed – hidden when “on the way from Last Island up the Bayou Boeuf.” The man had multiple belongings of Mr. Beatty and of others on the island, including: a diamond set, a mosaic set, a coral set, a gold cross and neck chain, a black jet necklace with gold mounting, three hair bracelets, a gold Geneva watch attached to a diamond belt pin, a gold thimble, a locket with hair in it, a breast pin, a small locket with hair, a gentleman’s breast pin, two hundred and ninety dollars in bank bills, and other small items. A letter from Bayou Boeuf printed in The Picayune on August 21, 1856 said, “… They were seen to drag the corpses from the water, rob them, tearing studs from the shirt bosoms of men and ripping the earrings from the ears of ladies. One was actually seen to push the head of a person repeatedly down into the water, as if trying to take from him the speck of life remaining, previous to robbing him.” A woman reported from the wreck of the Star that the pirates surrounded the island in tiny boats from their retreats along the bayous. She said one attempted to board the Star, but Captain Smith refused and prevented his entry. Eight of the looters stood trial aboard the Texas by twelve prominent St. Mary Parish men on August 20th, 1856. The proceedings led to the recovery of Emma Mille’s sister-in-law’s corpse, Mrs. Althea Homer Mille, who they had robbed. Two of the pirates were found guilty and were executed on the western end of the island half an hour before sunrise that day.

John Charlton Beatty

John Charlton Beatty Died 1808-1856 ORANGE GROVE PLANTATION, TERREBONNE PARISH Background Beattie and his wife Charlotte Reid were born in Kentucky. Beattie’s ancestors were originally from Scotland, settling in the United States as early as 1690. Job/Occupation John Carlton Beatty was a lawyer and sugar planter. Why On The Island John and his wife Charlotte were vacationing with their two young children. Storm Experience One of Beatty’s slaves on the Star who was at the Muggah Hotel when it began to shutter in the storm, saved one of Beatty’s children and Dr. Thomas Bryan Pugh, who was three years old at the time. The slave had pleaded with Beatty to follow him to higher ground, and when Beatty refused, he pleaded to take at least one child to safety. Beatty adamantly refused demanding his child to be put down, and that’s when the slave fled the hotel. The entire Beatty family perished, but the slave was able to save a child. During this escape, he had also managed to “pluck Pugh’s three-year-old son, Thomas, from the waves.” Interesting Fact Beatty’s son Taylor Beattie was a sugar cane planter, Lafourche Parish Judge, Confederate Army colonel as well as a candidate for governor of Louisiana in 1879 and Congress in 1882. His grandson, Carlton Reid Beattie, was a federal trial judge appointed by President Calvin Coolidge. Memory “My little girl [most probably the 3-year-old Francis Harriet] gave a scream and jumped and caught me around the neck and held fast, as if to choke the life out of me,” Schlatre recalled. Stay on Beatty’s Property Orange Grove Plantation, built for J.C. Beatty and his family in 1840, still exists near Houma, Louisiana. A Cajun cottage on the historic property can be rented through airbnb. airbnb

Rev. Robert Samuel McAllister

Rev. Robert Samuel McAllister Survived 1830 – 1892 Thibodaux, Louisiana Background Born in Abbeville, South Carolina, McAllister was serving as the third minister of the Presbyterian Church in Thibodaux from 1856-1859. Job/Occupation Presbyterian minister. Storm Experience Rev. McAllister left one of the most detailed accounts of the storm: August 10, 1856“On Sunday, Aug. 10, the weather got worse and by noon, it was dark outside with rain coming in torrents. The noon meal was served as usual but there was no talking at the table. “For while we all had a certain measure of misgiving, no one was yet willing to give expression to his fears.” Everyone sat and ate dinner as normal, but they all knew something tragic was going to occur. “At 3 p.m. the wind was howling. Lightning illuminated the sky and thunder rocked the island to its core. He likened it to the sound of distant guns. “We were shut up with no possibility of flight, on a narrow neck of land with two unbounded seas. In a strife of the elements like this, there would have been disaster even in midland; here on this sea-grit sand-bank it would be tame to say that we were in extreme jeopardy.” At this point, the weather was horrific and no one had a way to escape it. McAllister describes it as…”on a narrow neck of land with two unbounded seas…” Then the water stopped rising and stabilized for what Rev. McAllister said seemed like forever. “To my excited imagination it seemed that the elements were sitting in solemn council and engaged in debate as to what should be done with us.” Then the water level started to fall. It was as if “the angel of the waters brought a reprieve from the high court of Heaven, and with a shout which echoed throughout the dark, unfathomed caves of oceans commanded the release of the prisoners.” Interesting Fact In 1862, McAllister traveled two thousand miles in a buggy on a missionary tour of the South. Memory “If we could have been conscious that we were about to die for adherence to some great principle, then we would have been upheld by the thought that we were leaving footprints on the sands of time, for the encouragement of some forlorn and shipwrecked brother. But alas, not one of us was at the post of duty; not a soul on the island had any business there.”

Michael Schlatre

Survived 1819 – 1900 Enterprise Plantation, Plaquemine Background Michael Schlatre was born on April 10, 1819 on Homestead Plantation in Plaquemine, Louisiana. Job/Occupation Michael worked on his father’s sugar plantation; during this time, he learned carpentry work and blacksmithing; later he became the owner of Enterprise Plantation. Why On The Island The Pughs had been staying at Muggah’s hotels with Dr. John Carlton Beattie (1808 – 1856, Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court), his wife Mary Foley Beattie, and their two children from Bayou Lafourche. Storm Experience Schlatre survived the storm, but his wife and 7 children. He, suffering with a broken leg, and Thomas Mille floated for almost a week. “From my injuries I accepted that I would be the first to die,” Schlatre conceded. “Were you ever this near death, dearest reader? My children [seven] flocked around their father, some crying, some quiet, my wife facing the Gulf, the negro women crying, old Hannah with the baby sitting close to me.” Interesting Fact After breaking his leg during the storm, he walked with a limp for the rest of his life. He lost 7 children in the Great Storm and then went on to remarry and have more than 7 children after the storm. Memory “My little girl [most probably the 3-year-old Francis Harriet] gave a scream and jumped and caught me around the neck and held fast, as if to choke the life out of me,” Schlatre recalled.

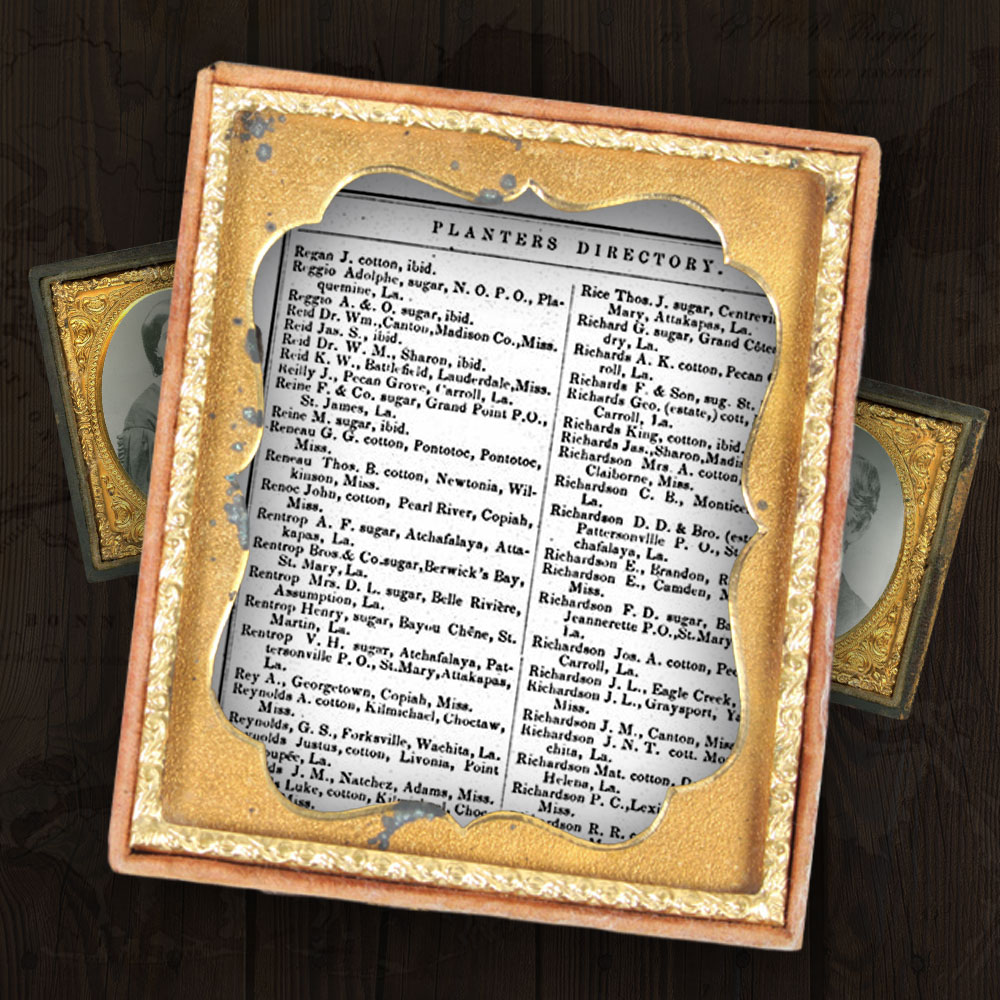

Modeste G. Rentrop

Died 1822 – 1856 Belle Rivière, Louisiana Background After her husband, D.L. Rentrop, died in 1853, Modeste and their daughter Marguerite, born in 1851 who also died in the hurricane, continued their family plantation. Job/Occupation Sugar planter. Storm Experience Unknown. Interesting Fact Her husband, Dorsino Louis (D.L.) Rentrop, died of yellow fever on October 25, 1853, in Berwick’s Bay, Louisiana. Wealth After her death, her landed estate and slaves in Assumption Parish were sold. The slaves sold at an average of $1,157 (about $35,000 today) and her land and stock sold for $50,600 ($1.5 million today).