Emma Mille Duperier

Survived 1837 – 1936 Plaquemine, Louisiana Background Zoe Emma Mille was born in Plaquemine, Iberville Parish, Louisiana on October 10, 1837, to sugar planter and French native Pierre Thomas Mille and his wife, Marie Pauline Dupuy. Job/Occupation None. Why On The Island Her family owned a summer cottage and spent summers vacationing at Isle Dernière. Storm Experience Emma was struck in the head by a piece of timber as her home collapsed and blew away. She fell asleep floating, resting on the same piece of timber that struck her head. When she awoke, she was on the sand, naked and badly injured surrounded by the dead and entangled in debris. Some slaves nearby recognized her as Thomas Mille’s daughter, so they found Richard, her father’s servant, in the hull of the Star. Hurt and weak, Richard carried Emma back to the boat so she could receive medical attention. Dr. Alfred Duperier sewed up a big gash on her head and left side. She then learned that her brother, Homer, his wife, Althee, and their baby were dead; her guest, maid, and parents were also lost. Interesting Fact Emma and Dr. Alfred Duperier, who cared for her injuries from the storm, fell in love and married just months later in December 8, 1856. She was also the last survivor of the Great Storm of 1856 to die. Memory “After our house gave away, there was no human voice. I drifted in that black swell all night clinging to the very piece of the house that had fallen on my head. Logs struck against me with the force of battering rams. It was then I heard Altea call, ‘Mamma. Look at Mamma.’ And there was my mother standing on wreckage. Someone was throwing her a rope. This was my imagination, of course. A vision. For I was paralyzed and totally alone in the gulf. You may think it strange, but I felt no fear. It never occurred to me that any of us could be killed. It was then I fell asleep with my face and chest on that piece of timber.”

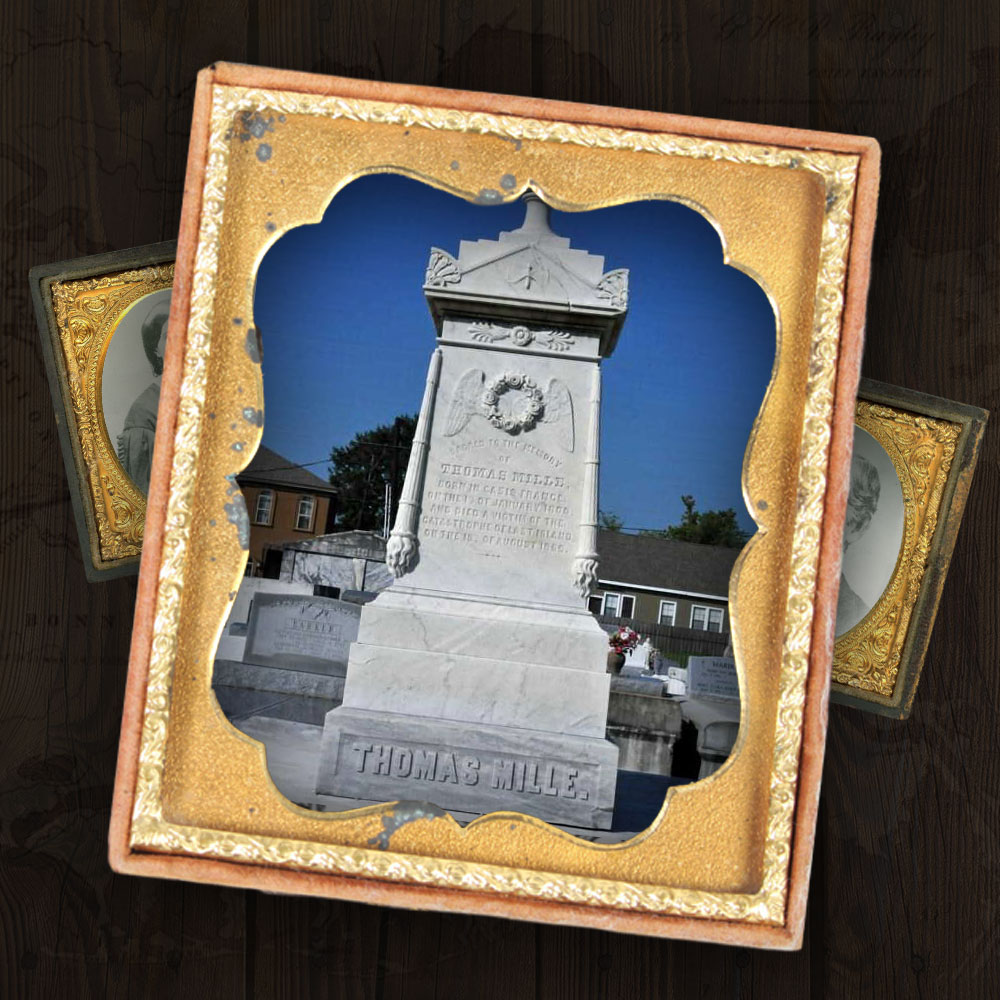

Thomas Mille

Died 1800 – 1856 Plaquemine, Louisiana Background Born on January 11, 1800, in Cassis, Bouches-du-Rhône, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, France. He married Pauline Dupuy in Saint Gabriel, Louisiana. Job/Occupation Sugar plantation owner. Why On The Island Owned a summer cottage and vacationed at Isle Dernière with his family. Storm Experience Sugar planter Thomas Mille’s slaves fled their timber shack as it began to blow apart, and they ran to Mille’s house. One slave, Richard, tried to convince Mille to move his family and slaves into a stable built with sturdy, deeply driven pilings. Mille refused. Mille’s slave Richard hid out in the stable, the only building the storm didn’t level. After the storm, he was missing and presumed dead, but Michael Schlatre and Thomas Mille were separated from the others on the Last Island and were able to reach New Orleans after five days on a makeshift raft. They were found by Captain Charles W. Brien’s crew, who loaded the men onto Brien’s boat and took them back to his home. Mille died four days after he was taken to safety. Interesting Fact Mille was rescued by a passing ship five days after the storm, but died two days later due to dehydration and starvation.

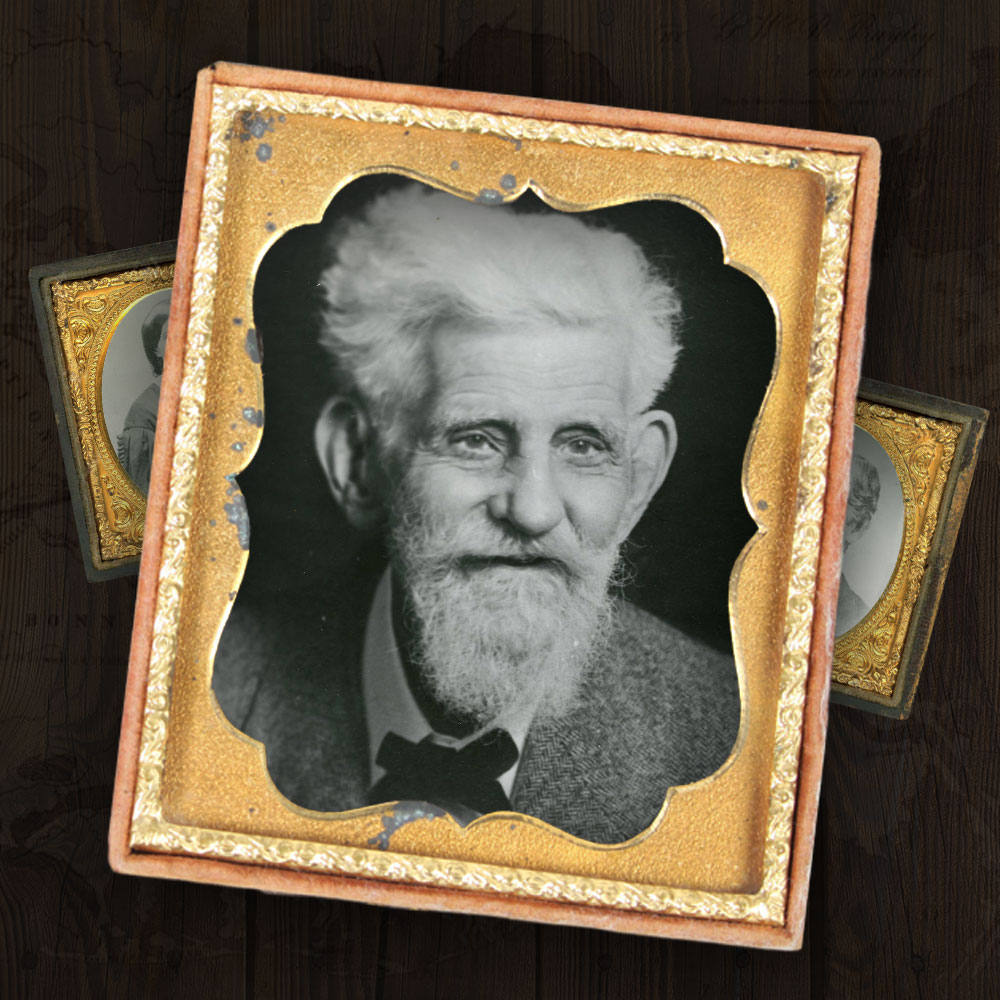

Capt. Abraham Smith

Survived 1831 – 1890 Born in Proctorville, Ohio Background Born in 1831 at Quaker Bottom near Proctorville, Ohio. He assisted his father on his farm until he was 17 when he accepted an offer of a captain on a merchant vessel to go to sea. Job/Occupation Captain of the steamer The Star that made a round trip three times a week to Isle Dernière. Why On The Island Abraham came to Louisiana in 1854 and was placed in command of the steamer Texas, engaged in lower coast trade. In 1856 he became captain of The Star, which connected the Opelousas Railroad and plied through waters of St. Mary Parish, the Atchafalaya, Four League and Caillou Bays to Last Island. Storm Experience Capt. Smith battled the winds and guided the Star through the storm all Saturday night to get to back near the Louisiana mainland in Caillou Bay on Sunday (the day the storm hit). “Sunday morning, crew on The Star, a steamboat ferry, debated whether to turn back inland after losing its bearing in the storm, “but Captain Abraham Smith, concerned about the fate of those left on the island, insisted on returning amid the hurricane – a decision that saved many lives.” Guests formed a human chain arm-to-arm from the hotel to The Star to reach shelter on the steamboat. Captain Smith moved all passengers into the cargo hull beneath the cabin Monday morning and The Star wedged into the earth in the place of Muggah’s Hotel. The Star’s top decks were ripped off, but the hull stayed afloat and saved 160 people. Pirates swarmed the island to search through the carnage looting for valuables and when they attempted to get on board the wreck from The Star, Capt. Smith prevented it. Interesting Fact Capt. Smith was a hero twice in his life. After becoming a captain again, in 1876, he saved all 40 passengers aboard the Minnie Avery when the boat hit a snag and sank in the Atchafalaya bay. He was reported to be 6 feet 6 inches tall. The average height, according to Time was 5 feet 10 inches for an American male in the 1800s.

Richard

Survived unknown – unknown Plaquemine, Louisiana Background Unknown Job/Occupation A slave of the Thomas Mille family. Why On The Island Came with the Mille family as a slave to serve while they were on the island. Storm Experience Richard tried to convince Mille to move his family and slaves into a stable building with sturdy, deeply driven pilings. But Mille refused. According to Smithsonian Magazine, “Richard hid out in the stable, the only building the storm didn’t level. Emma Mille, the planter’s 18-year-old daughter, was one of several survivors who grabbed pieces of wood as they were swept out to sea, then held on until the storm shifted and cast them back onto the island. Richard found Emma on the beach, deeply wounded, and brought her to Alfred Duperier, a doctor who had survived the storm by tying himself to an armoire and floating on it for 20 hours.” Interesting Fact Richard brought his owner’s daughter, Emma, who was badly injured in the storm to a doctor. While treating her for her injuries, the 30-year-old widower, Dr. Alfred Duperier, and Emma fell in love and married that December.

John Muggah

Died 1812 – 1856 Saint Martinville, Louisiana Background Son of James Milne Muggah, a Scottish immigrant, and Julianna Robbins. The family, including sons John, Henry and David R. lived in Patterson in St. Mary Parish. John was married to Mary A. Patterson and had two sons, Edward and Frances. Job/Occupation Muggah was a businessman/merchant. He owned The Star steamship and the Muggah Hotel. Why On The Island John owned a summer home and, along with his brothers, owned the hotel and steamship. Storm Experience John, his wife, their two sons and five servants all died in the storm. Specifics are unknown. Interesting Fact John, along with his brothers, partnered with a consortium of other planters and bankers to triple the size of the Muggah Hotel. Construction was set to begin at the close of the 1856 summer season.

Cyprien August Barrilleaux

Died 1825 – 1856 Plattenville, Louisiana Background Son of Francois Barrilleau from France. C.A. was living with his father and siblings in Assumption Parish in 1850 where his father’s real estate was worth $35,000 in 1850 ($1.17 million in 2020 dollars), according to the 1850 US Census. Job/Occupation Justice of the Peace. Storm Experience In a newspaper clipping from 1856, it said “Mr. C.A. Barrilleaux particularly distinguished himself at this time, and finally fell a victim to his bravery and resolution. He had rescued nearly all of Mr. Pugh’s family, and went back to render assistance to that of Mr. Beatty, when the exertion proved too much for him, and he sank with a lady whom he had in his arms endeavoring to save, and they rose no more, all attempts to reach them proving utterly fruitless.” Legacy Barrilleaux’s wife, Pauline, was 5 months pregnant when he died. His son, Cyprian Arthur Barrilleaux was born in December of 1856.

Dr. Thomas Bryan Pugh

Survived 1853 – 1952 born at Woodlawn Plantation, Napoleonville, Louisiana Background Dr. Thomas Bryan Pugh was born and raised on Woodlawn plantation. His parents, Colonel William Whitmel (W.W.) Pugh (1811 – 1906) and his wife Josephine Nicholls (1820 – 1868), lived at Woodlawn Plantation, “a classical columned, three-stories palace on the bayou,” near Napoleonville, “with 14 lavishly furnished bedrooms,” according to a profile of famous Assumption Parish people. Job/Occupation Dr. Thomas Bryan Pugh was a long-time doctor in Napoleonville. After graduating from the University of Virginia he attended Washington & Lee University, then graduated with a medical degree from Tulane University. Dr. Pugh practiced medicine in Assumption Parish where he served as health officer and was coroner for two terms. He also served as the mayor of Napoleonville for two terms where he was a vestryman of the Episcopal Church and on the directing board of the Bank of Napoleonville. Why On The Island The Pughs had been staying at Muggah’s hotels with Dr. John Carlton Beattie (1808 – 1856, Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court), his wife Mary Foley Beattie, and their two children from Bayou Lafourche. Storm Experience Pugh’s father, Col. W.W. Pugh, speaker of the LA House of Representatives, was on the island the weekend of the storm. He recounted that Friday night the water was angry with very high waves and Saturday the marshes were submerged and cattle on the island were pacing and lowering. Col. Pugh, his wife, and children were washed away from their shelter behind what remained of the Muggah Hotel dining room. They were able to grab the remains of a large cistern. W.W. Pugh wrote, “A ferocious gust of wind was followed by a tremendous cry of agony. Then darkness and lashing of winds. To the risk of being washed off was added the danger of immediate death from planks hurled through the air in all directions. I witnessed one of the Muggah brothers, who owned the hotel, meet his end in this manner. My wife, Josephine, lifted Thomas, our three-year-old son, over her head. The nurse held up Loula, our baby daughter. Finding the nurse frantic with fear, Josephine took Loula in her arms, charging the nurse to get a firm grip on Thomas’s little hand. We were startled to hear a childish voice ring out over the violent crack of thunder and lightning and the roar of the wind [Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep…] It was the last thing we heard before an avalanche of water overtook us. You see, it was the only prayer the little lad knew. Just then a terrific wave rushed over us bearing Loula from Josphine’s arms, while Thomas and his nurse vanished into the sea.” Thomas Ellis found Col. Pugh, Josephine, and their four children hopeless over the fate of Thomas, whom they had not seen since the incident by the cistern. After the storm, the Pughs found one of Dr. Beatty’s slaves on the Star who was at the Muggah Hotel when it began to shutter in the storm, who had saved one of Dr. Beatty’s children and Dr. Thomas Bryan Pugh, who was three years old at the time. The slave had pleaded with Dr. Beatty to follow him to higher ground, and when Beatty refused, he pleaded to take at least one child to safety. Beatty adamantly refused demanding his child to be put down, and that’s when the slave fled the hotel. The entire Beatty family perished, but the slave was able to save a child. During this escape, he had also managed to “pluck Pugh’s three-year-old son, Thomas, from the waves.” W.W. Pugh reveals that he gave the slave a gold watch, which he later proudly exhibited serving as a Reconstruction Era politician. Interesting Fact “The Pugh family’s status as ‘the best people’ was so well known that there was a popular riddle making the round of the Gulf South – ‘Why is Bayou LaFourche like the aisle of a church?’ Answer: ‘Because there are Pughs on both sides.’ “W.W. Pugh was part of the family consortium who owned ‘Allied Plantations,’ eighteen plantations each with close to 1,000 acres, sprawling across the parishes of Assumption, Terrebonne, and Lafourche. By 1860, the ‘Allied Plantations’ annual income is estimated to have been more than six million dollars annually (in today’s dollars).” Memory “My wife, Josephine, lifted Thomas, our three-year-old son, over her head,” wrote Thomas Pugh’s father Col. W.W. Pugh. “The nurse held up Loula, our baby daughter. Finding the nurse frantic with fear, Josephine took Loula in her arms, charging the nurse to get a firm grip on Thomas’s little hand. We were startled to hear a childish voice ring out over the violent crack of thunder and lightning and the roar of the wind [Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep…] It was the last thing we heard before an avalanche of water overtook us. You see, it was the only prayer the little lad knew. Just then a terrific wave rushed over us bearing Loula from Josphine’s arms, while Thomas and his nurse vanished into the sea.”

A Resort is Born

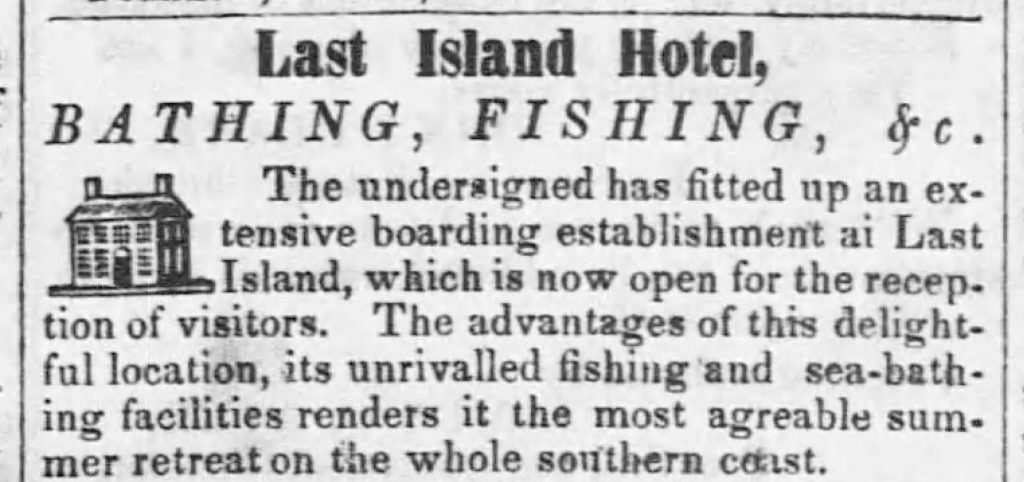

By Michael Gros Brand & Visual Editor “Five years ago Last Island boasted only a few fisherman’s huts – its beach served the useful purpose of drying fishermen’s nets. Today it has a fine hotel, and more than twenty commodions private residences, all occupied during the summer: its beautiful beach, twenty-one miles in length, smooth as a mirror and elastic as a spring-board, teems every evening with people, composed of sober-sided old gentlemen as pedestrians, fast young men and ladies on horseback, and carriages innumerable whirling along at a pace that would astonish the frequenters of the shell road, freighted with the fair daughters of Western Louisiana.” By the 1840s, developers began to purchase land from the US government for $2 an acre, which is about $52 in today’s currency. While planters were building summer homes on the island, there was an outcry for more accommodations than what was already provided. In 1848, the four Muggah brothers along with financers from St. Mary Parish developed the Ocean House Hotel. The goal was to make this the finest summer resort in the south and wanted to rival the summer getaways of places like Newport. A getaway that gave relief from the summer heat as well as yellow fever. The Ocean House Hotel is sometimes known as John Muggah’s Ocean House Hotel, The Muggah’s Hotel, the Last Island Hotel, or, as it was said in an open letter to The Daily Delta, Last Island St. Charles. It was not a grand structure, rather a two-story wooden structure that was said to be of “considerable strength.” There were about 40 rooms, to which one guest said, “Behind the hotel was a dock where island visitors would disembark the Muggah-owned Steamer The Star. The Star would ferry island visitors to and from the mainland, once in the morning and once in the evening. By 1856, the New Orleans/Opelousas railway connected to the Great Western Railway offered people passage to the Algiers station for only $3.50, roughly $100 today, and half fare for children and servants. The hotel included many amenities including a billiard hall, bowling, a carousel and ballroom. However, the place that everyone seemed to gather and enjoy themselves was the restaurant. Upon entering the restaurant, you were greeted by accomplished hostess, Mrs. Pecot. Being on the coast offered a wide variety of fish, terrapin, and shellfish, and Captain Dave Muggah, President of the Last Island Dinner Club, was there to navigate guests through the various seafood options. A bar was kept by Mr. Martin with wine and sangarees. According to Directions For Cookery In Its Various Branches by Miss Leslie, an 1837 cookbook, she describes the sangaree as the following: “Mix in a pitcher or in tumblers one-third of wine, ale or porter, with two-thirds of water either warm or cold. Stir in sufficient loaf-sugar to sweeten, and grate some nutmeg into it.” “The hotel at this place is very well kept; the table generally abounds with every luxury and delicacy within the control of the proprietors, whose extreme attention and politeness to their guests and solicitude for their comforts, contribute to render this a very desirable sojourn during summer.” The Daily Delta, August 20, 1854 By the early 1850s, there was a major outcry for more accommodations on the island. The four Muggah Brothers heard this, and in conjunction with the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans, plans for a bigger, more elaborate hotel dubbed the Tradewinds Hotel were being drafted. Construction was slated to begin after the summer season in 1856. Directly to the west, about several hundred yards was the Last Island Village. In this village, David Muggah also owned a hotel called the Waxota. The village also consisted of several gambling establishments, a racetrack and livery and the beginning of around 100 summer homes for the planters that stretched to Racoon Point. During those lazy, summer days, people were able to walk the pristine beach, go for a joyride on horseback or by carriage and take a spin on the carousel. Because this oasis was built on fishing, men were able to take paddle boats out into the gulf and neighboring Lake Pelto to fish for flounder, pompano, and red snapper. Directly to the east of the hotel, not much is known about development. Various maps and the 1853 U.S. Geologic survey list this area as the duck ponds. Today, we know the Louisiana duck season to be early November to early January. “Shooting and riding and boating are the sports in which the ladies most indulge; in both of which two ladies from Iberville are preeminently superior to all others. They are dead shots, and whenever they sally forth with dogs and guns they bag more game in an hour than any two gentlemen on the island could do in double that time. One of these ladies is the most intrepid, graceful and daring rider that I have ever seen. She seems as much in her element on a prancing pony, bounding over logs, rails and fences and bayous, as she does in dancing the quadrille or polka, in either of which she displays that grace and elegance which always distinguish the Creole ladies of Louisiana.” The Delta in New Orleans (August 20, 1854) drawing resorters Previous Next a refuge from YELLOW FEVER watch a video about Yellow Fever in New Orleans by the Historic New Orleans Collection an island meal traveling to Isle Dernière The trip to Isle Dernière took days with travelers going by rail to steamboat in the gulf or by steamboat along the bayous and then into the gulf to the island.

The Island Oasis

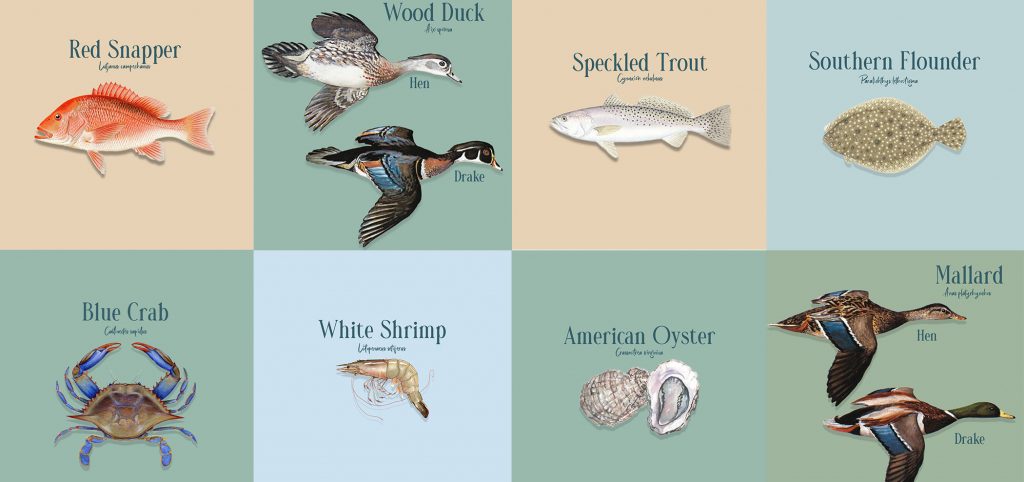

the wildlife Wildlife flourished along the coast of Louisiana, especially around the barrier islands. This abundance is part of what drew people to the island to establish the resort. in the ocean White Shrimp Speckled Trout Southern Flounder Red Drum Pompano Brown Shrimp Red Snapper Amercian Oyster Blue Crab in the air Wood Duck Mallard Green-winged Teal Gadwall Blue-winged Teal American Wigeon American Black Duck the diary of an Explorer Alvar Nuñez Cabeza De Vaca, a Spanish explorer, kept a diary of his experiences in the Gulf of Mexico in 1542. Read Diary PODCAST Dr. Gary LaFleur, Louisiana native and professor of biological sciences at Nicholls State University, discusses Isle Dernière before it became a popular resort. Garde Voir Ci · Season 3, Episode 1 – Isle Dernière Before the Storm with Dr. Gary Lafleur

The Lost Bayou: Isle Dernière

by Payton Suire Managing Editor At one time, Louisiana’s coast was a white, sandy beach and blue-water destination. An oasis for the rich and powerful sugar planters. But the beauty of this paradise and the wealth of its visitors provided no protection from the deadliest storm to hit Louisiana’s coast. This unnamed storm that erased the summer resort of Last Island, Isle Dernière, was the worst to hit Louisiana until Hurricane Laura in August 2020. “Those storms all have become legendary. It’s part of your psyche now. The difference between 1856 and any of those other storms that impacted LaFourche Parish, is that, and I say politely, those people could read and write,” said John Doucet, author on early Louisiana hurricanes and dean of Nicholls State University’s College of Sciences and Technology. “They say that 2/3 of all the millionaires in the United States lived in Louisiana at the time. Much of the wealth of the United States diminished that night. First because of the death of the planters, but also, when a planter dies, the wealth has to be divided between the children.” Today, weather forecasters use data from radars giving residents days to prepare. Laura was tracked in the Gulf of Mexico more than a week before the storm hit. And while predictions and models are still imprecise — for Laura, hurricane warnings were in effect from New Orleans to the East Texas coast — any advance warning gives residents and officials time to order evacuations. 500,000 people during Laura were evacuated and prepared, according to news reports. Unfortunately, in 1856, the vacationers on Last Island were naive to the tragedy forming in the Gulf and largely unaware of what was to come. Despite the warnings from crew on the steamboat Nautilus, capsizing only a few miles off the island, the cows pacing and lowering in the fields, or the waves as high as houses forming on the horizon, resorters believed everything was perfectly fine, according to the book Remembering Last Island. Even while the storm moved onshore and the winds swirled, vacationers partied at Muggah’s Hotel, the most popular spot on the island. “We did not know then as we did afterwards that the voice of those many waters was solemnly saying to us, `Escape for thy life,’” said survivor Rev. R.S. McAllister of Thibodaux, Louisiana in his memoirs A Minister Tempered by the Elements. Within two minutes water covered the island, washing away all structures and wildlife. Of the 400 on the island, 198 were dead, according to the 2017 Smithsonian Magazine article, A Hurricane Destroyed this Louisiana Resort Town Never to Be Inhabited Again. Those who survived barely escaped, witnessing the fate of those around them. In those times, the only way on and off the island was by boat and help took 5 days to arrive, leaving survivors scattered in the marsh, many injured, living off of crawfish and rainwater. “The jewelled and lily hand of a woman was seen protruding from the sand, and pointing toward heaven; … and again, the dead bodies of husband and wife, so relatively placed as to show that constant until death did them part, the one had struggled to save the other,” McAllister says. “And, more affecting still, there was the form of a sweet babe even yet embraced by the stiff and bloodless arms of a mother. Sights like these suddenly presented, gave a shock never to be forgotten, and called up certain feelings which no language can describe.” Even today, southwest Louisiana’s hurricane-Laura ravaged areas are still digging out from the debris and destruction a month after the storm hit. Last Island, which was completely submerged and broken into multiple pieces, never again housed a community. The only evidence of the short-lived, yet vibrant resort oasis is the historical marker erected in 1959 in Gray, about 45 miles north of the former Last Island. The small strips of sand that once formed a single island are now a bird sanctuary for pelicans and other water birds.